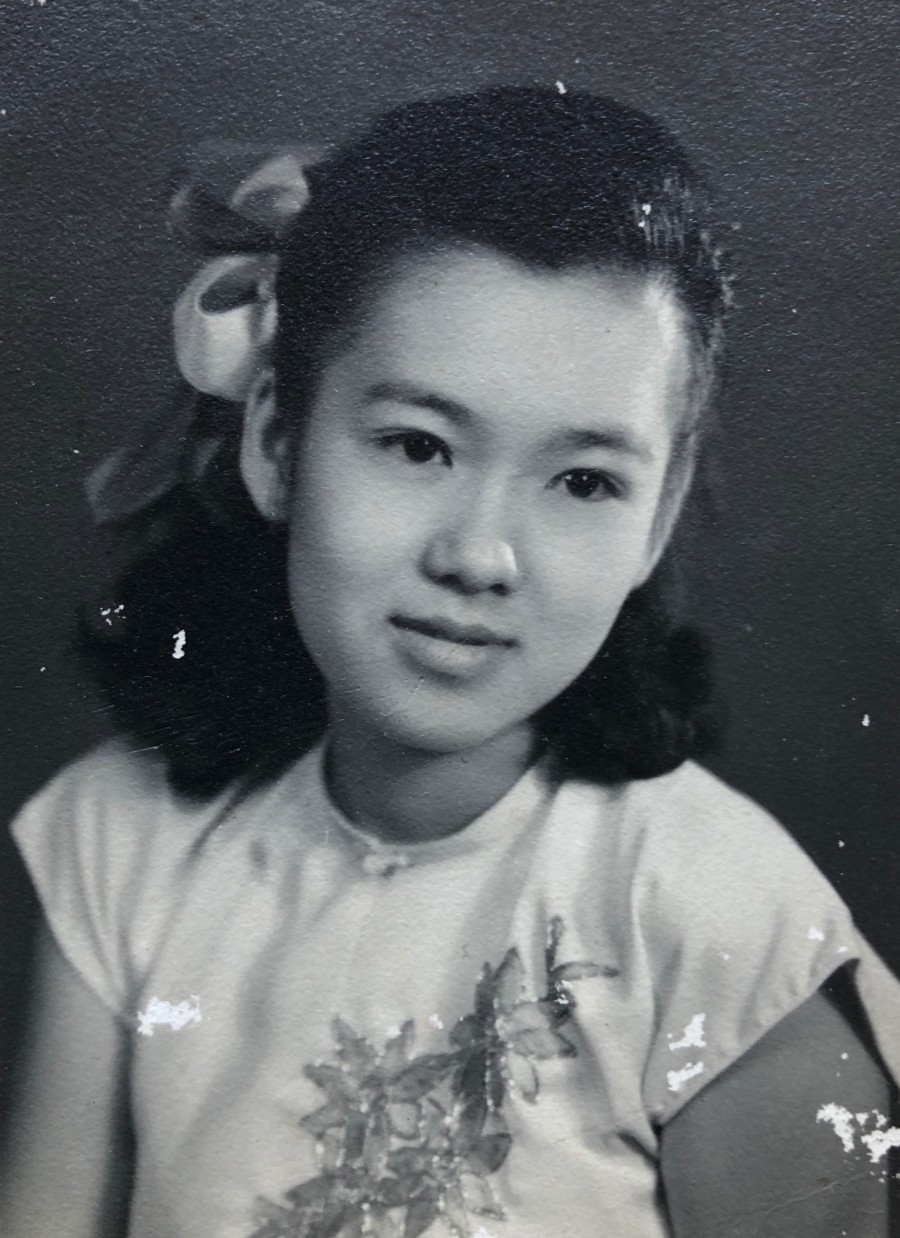

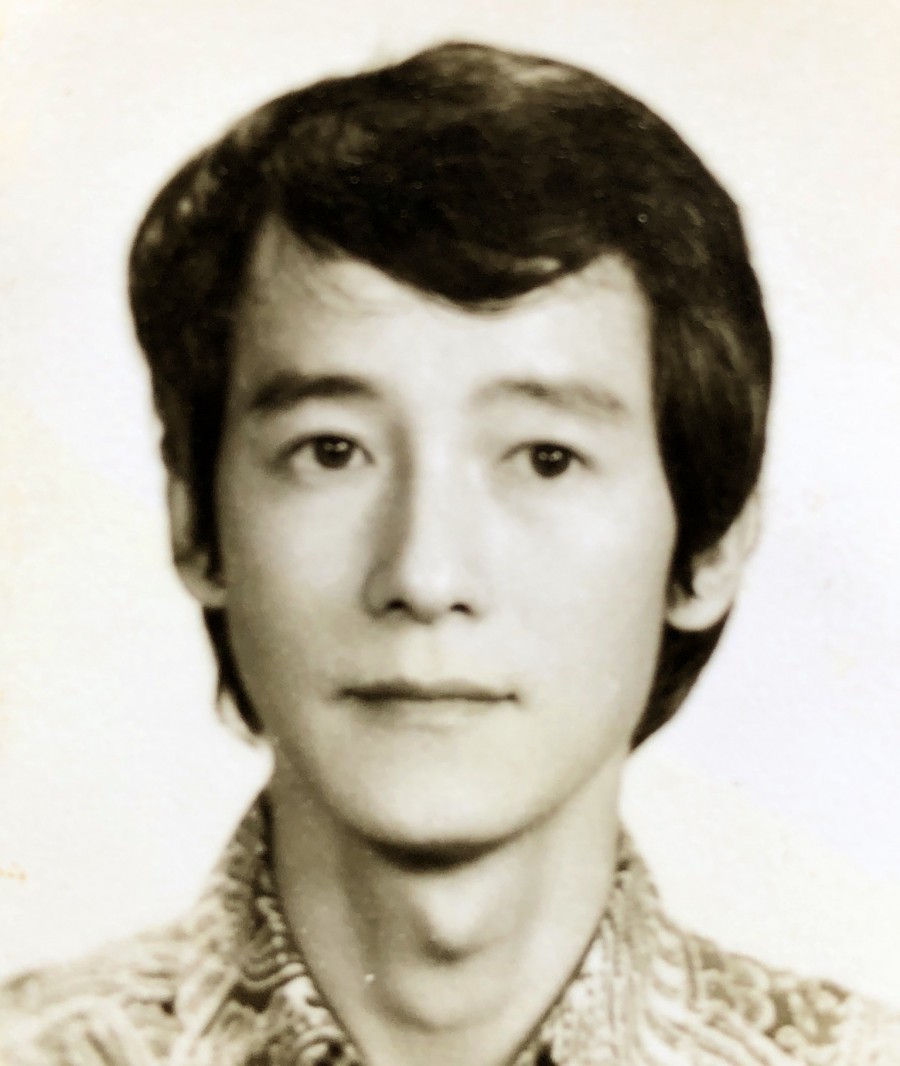

Pek-Lin Chiew Wong

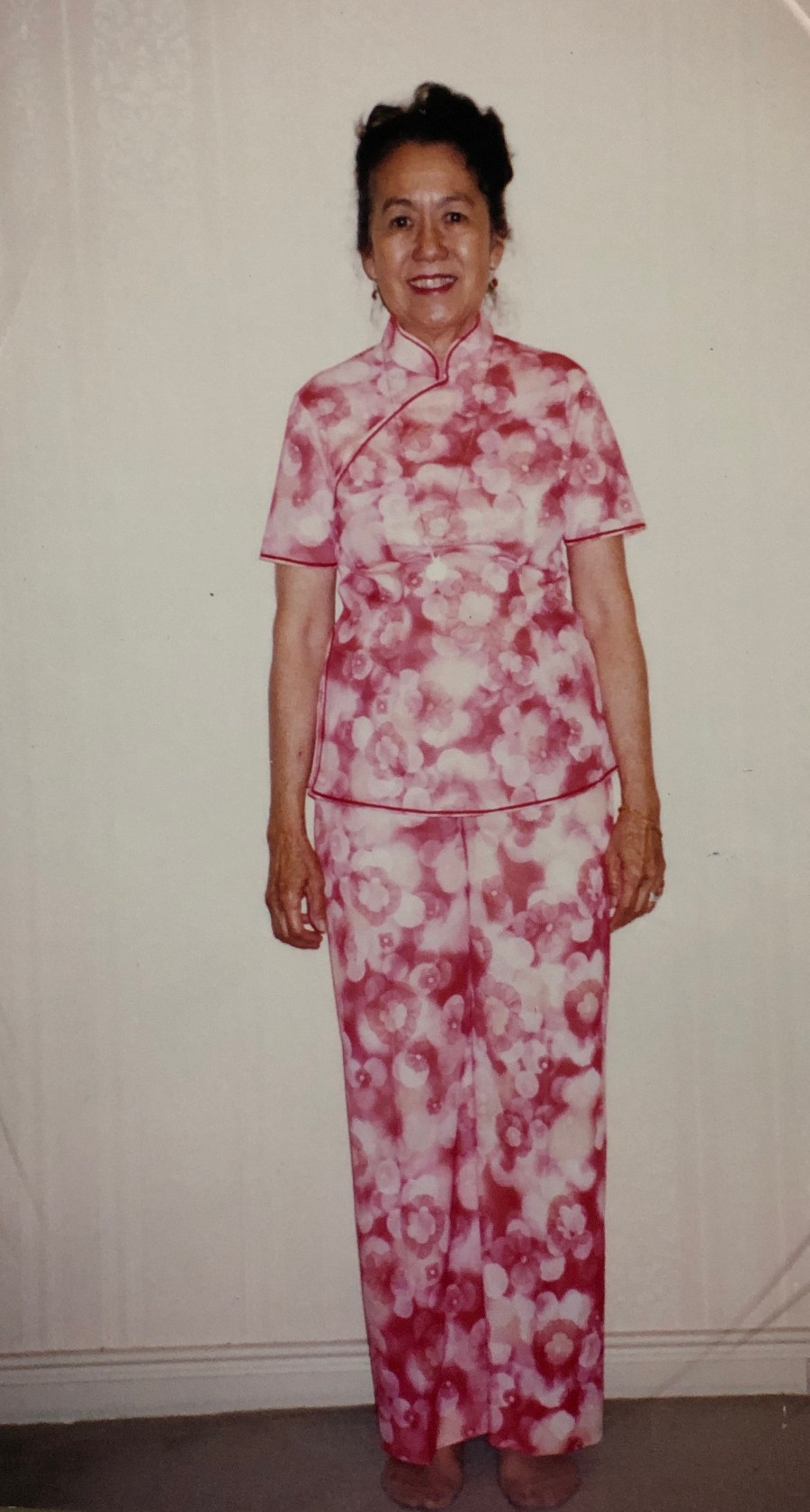

Born 14th of May, 1930 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Early Life

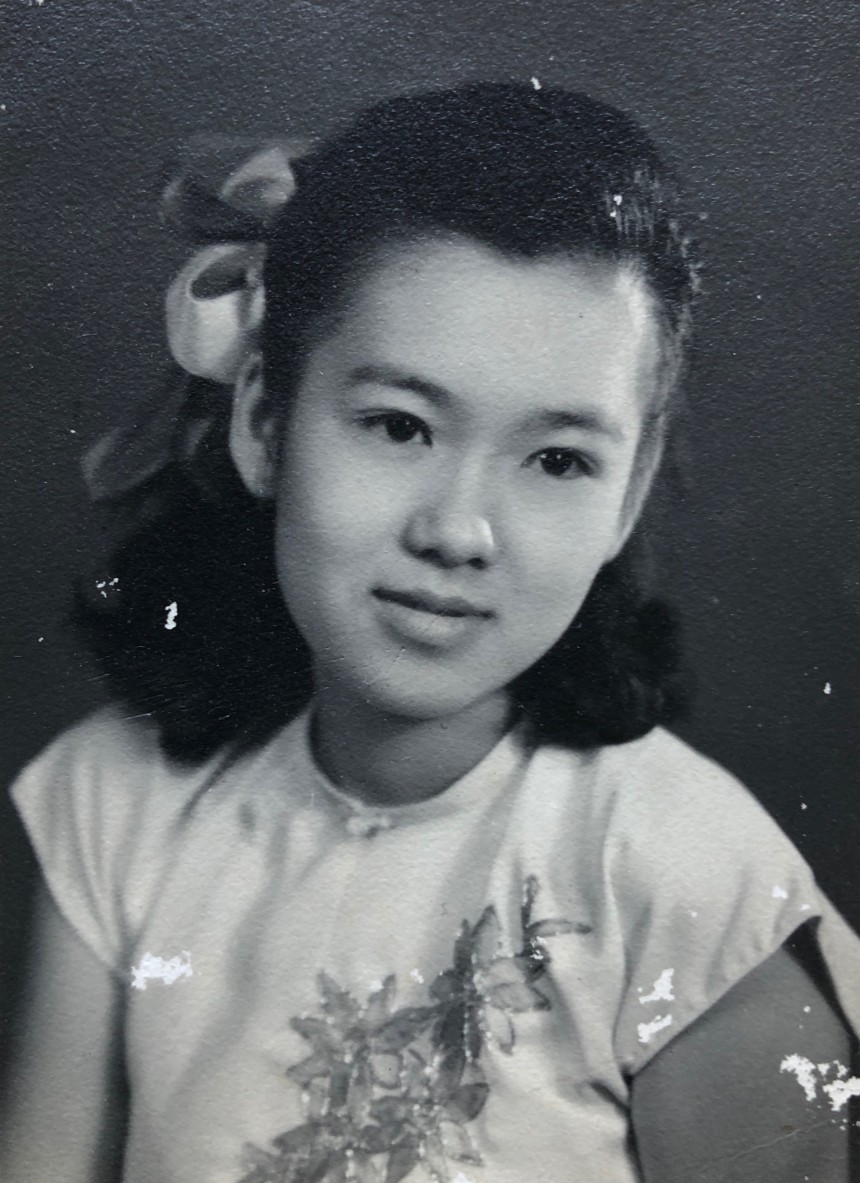

I was born on the 14th of May, 1930 in Kuala Lumpur, Southeast Asia. During that time, the country had a mixture of all sorts of people. A lot of people came from the borders of mainland China. This is because they were very poor and needed to find somewhere where they could make good. There were many Chinese who emigrated from China to Southeast Asia and found a more comfortable life there.

Because my grandmother came from a mixed cultural background, I was given a Malay name. So I didn't have a Chinese first name. The surname always comes first. My surname, Chiew, is Chinese. Then my other two names are Malay. Nya Chit. Nya means girl and Chit is ‘a little girl’ in Malay. So on my birth certificate, my name is Chiew Nya Chit. I lived with that right through my schooling. My Cambridge School certificate is under Chiew Nya Chit.

My father produced seven children. I'm number one. And then he had six after me. Four boys and two girls. Being the first child, I was born in a hospital. My other six siblings were born at home. Actually, one of my brothers was born in a pee pot. My mother couldn't reach the bathroom fast enough.

So after me, I have four brothers and two sisters.

The funny thing is, I've got this Malay name, but the boys have got proper Chinese names. Because they're boys, they're going to carry on the name. My brother, Chiew Thiam Yew was born after me. Chiew, that’s the surname. Thiam is to ‘add on’ in Chinese and is the family name. All the boys receive the name Thiam. Yew means ‘to have.’ Then came Chiew Thiam Choy. Choy means ‘wealth’ in Chinese. So the idea is that number two, he will be great and child number three, he’s going to have property, a lot of money. Names are given with expectations that the family hope the child will grow to live up to.My brother, Chiew Thiam Seng was born next. Seng means 'to succeed'. My next sibling to be born was a sister - Chiew Pek-Kwan. Kwan means ‘a group.’ Now, you will find that the girls have Pek in their names. My parents didn't have any more children until after the war. My youngest brother, Chiew Thiam Loy was born after the Japanese War. Loy means ‘come on’ in Chinese. Just come on! I was eighteen years old by this time. My youngest sister, Chiew Pek-Chan followed after that. I am twenty years older than her.

My earliest memory is of my brother, Thiam Yew taking my toy doll off me. The doll was given to me by some rich woman. I loved that doll very much. And because I loved the doll, he took it and beat her head against the window upstairs and I cried.

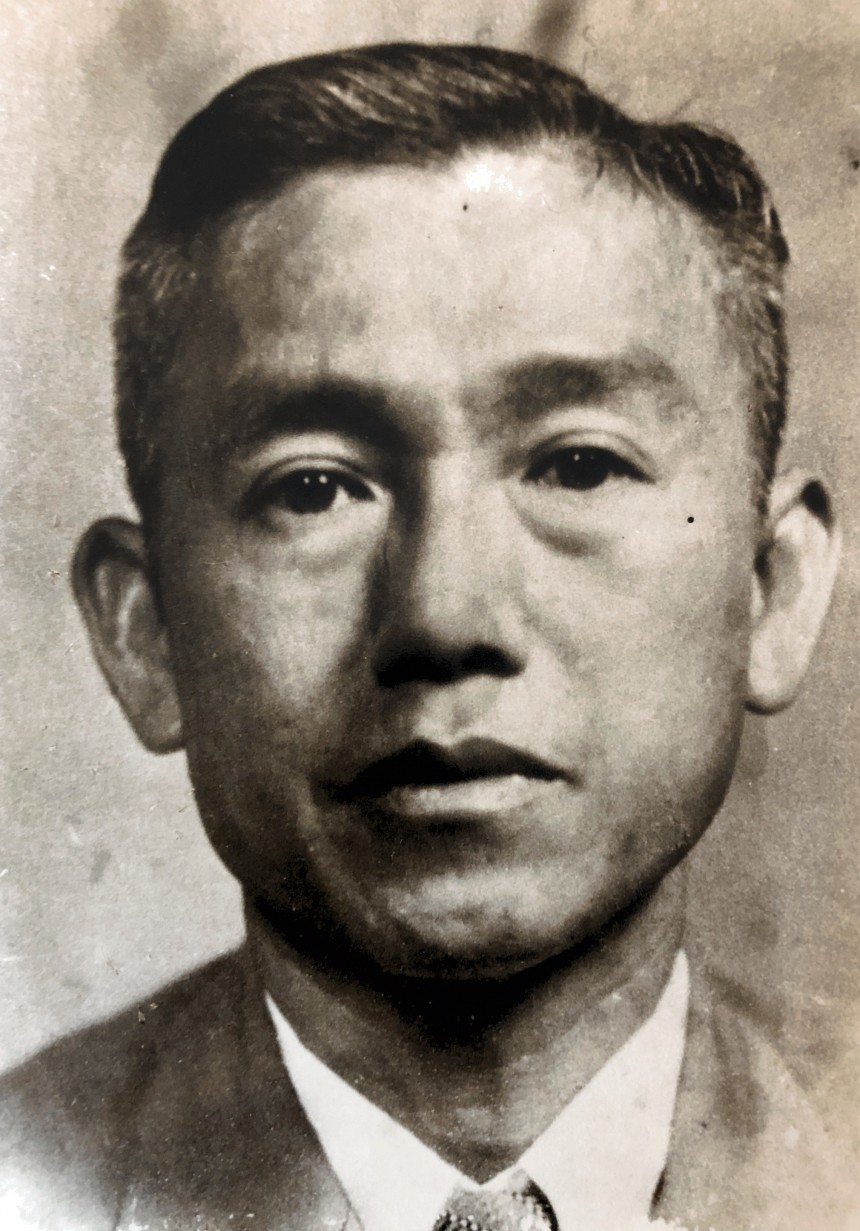

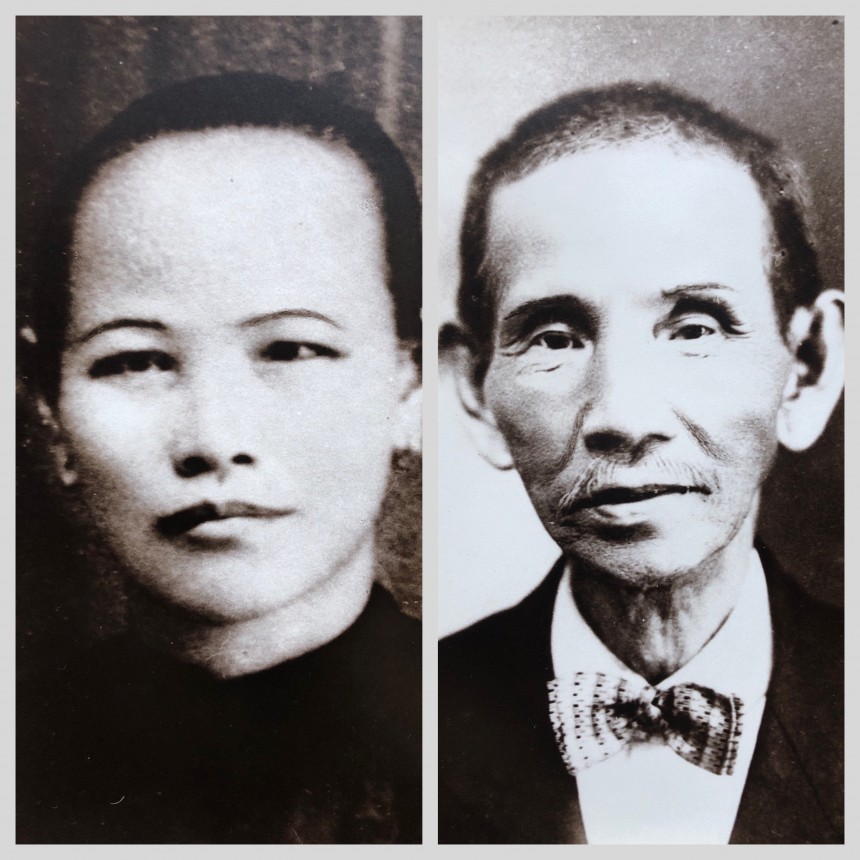

My Parents

My grandmother on my father’s side, married three times. The first man he married produced my father. She went on to have more children after my father. She was probably born in Malaysia. She had several, I wouldn’t call them marriages, but serious relationships, and had children with each partner. This was the way in Malaysia at the time. There wasn’t the expectation that one would marry a partner in order to start a family. As relationships ended and began.

I remember when I was a child, suddenly I had an uncle appearing and that uncle was from another man and he found my father. They looked for one another and suddenly I got a new uncle. I don't know who took him on, but he went to school, learned the English language and became a school headmaster.

As a child, everyone knew my name as being Chiew Nya Chit. My father was a very smart and far-sighted man. He said, "One of these days, China's going to come out tops, and all of you will have to learn Chinese." So we went to an English medium school in the morning and then in the afternoon, we went to a Chinese school. We did this every day. And then went to this Chinese school. My mother took us to be registered and that headmaster says, "No. She's not Chinese. She's got no Chinese name. "Chew Nya Chit. That's not Chinese. She's not coming in." So my mother had to go to a temple and she has a friend who's an abbess. A very well educated, Chinese abbess.

So yes my father was a bright chap. He became the chief clerk of a firm of English lawyers. At that time, most Malay people were intimidated by white people and saw them as big bosses. My father held the key to the office and held a senior position there so he wasn’t about skin colour. When I was growing up with my brothers, our school was just up on top of the hill to my father's office. So when we finished school each day, we would walk down the hill, go to his office and wait for him to finish work. Then I would be sitting in front of his bicycle or at the back of his bicycle. He would be bicycling two of us, me and my brother - two. Looking back on it, it was a very hard time but when we were living it, it seemed ok. Somehow nobody complained.

My mother wasn't a very sensible woman either. She had a little bit of money, and would show off to people who wanted to borrow money from her. Then she cultivated a very bad habit of gambling as well. This had a negative impact on our family's financial state.

When I was a child I would get up early, at 5 am, every morning. My mother always believed that the moment you get up, have a bath, a cold bath so that you become alert. Then I’d join my mother in the kitchen, pounding chilly to help her make laksa. After that, we’d sell it on the street. That’s how we managed to survive.

My mother was adopted. She also had a very sad story. She came from China. She was an only child and her parents brought her to settle in another part of Malaysia. Not in Kuala Lumpur, but in the Northern part - in Taiping. And then what happened was, it seems there were only three of them. They were robbed and then all their possessions were taken away and according to my mother, her parents said, "We better go back to China. This is not the place for us to live." But they had nothing. They had no money to go back to China and the only possession they had was the girl, my mother.

They sold her to a rich family. The surname of this family was Chong. My grandparents then had money they needed to go back to China. What happened to them? Nobody knows. That was the end of my mother's biological history. So she was sold to this new family who didn't have a girl.

I don't think her adoptive parents could have been very loving towards her because when she was a teenager, they forced her to marry a rich old man.

But my mother was a very bold woman. It seemed she escaped. She jumped from the window of the house she shared with this man and she escaped. And then, I think she rented a room somewhere, I don't know where. And that's where she met my father, who also was renting a room somewhere there. So that’s how they met and eventually they were married. They're two of a kind, my parents.

They stayed together. My father never went to look for another woman. But she developed bad habits, gambling. She would go tell, "I gamble, I win money. I bring money home." It was a lie, of course. How can you be all the time winning money?

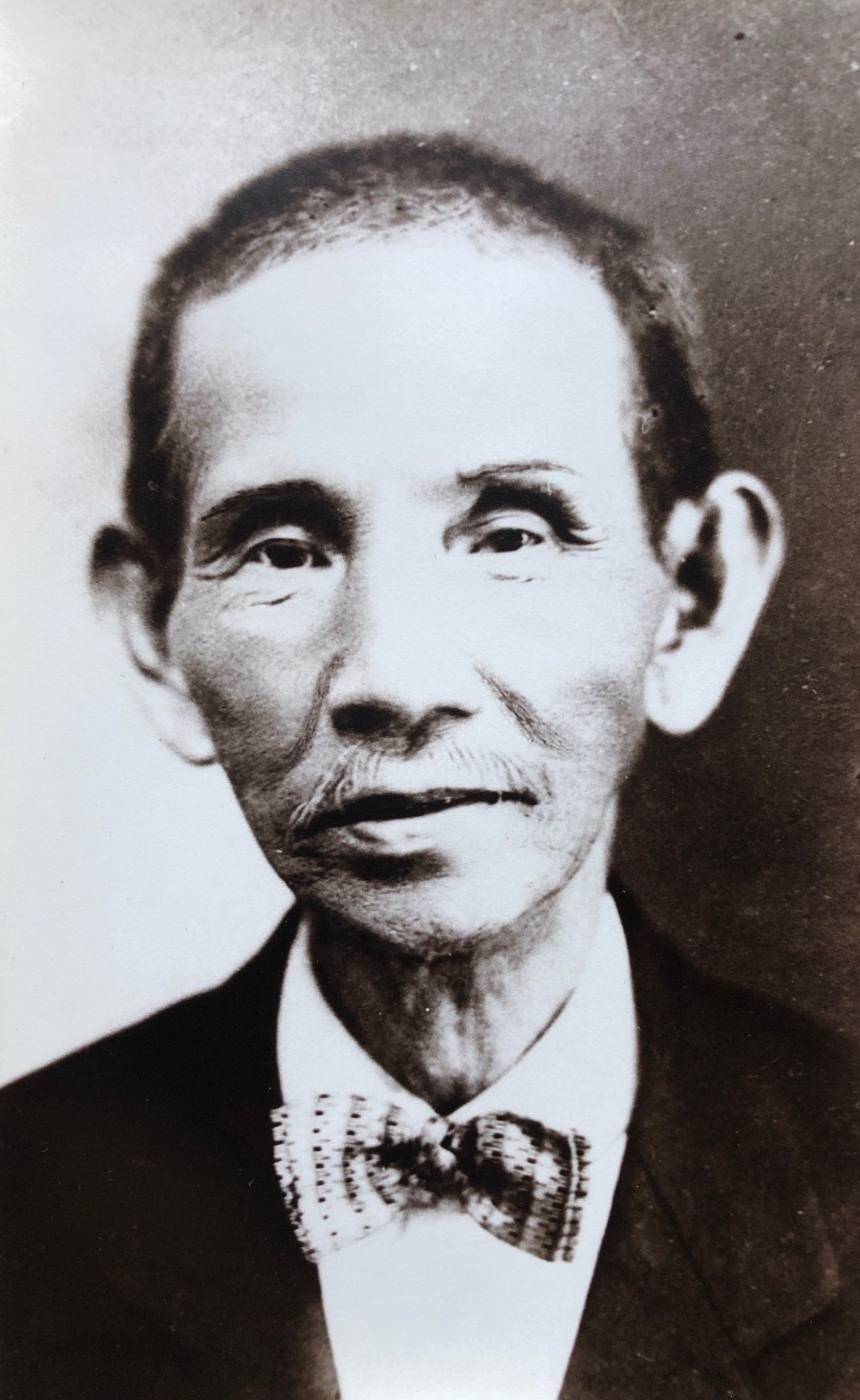

My Grandparents

My paternal grandfather was from China. For most of my life, I knew very little about him. I thought to myself, "Now, where do I start to find out more about my ancestors?"

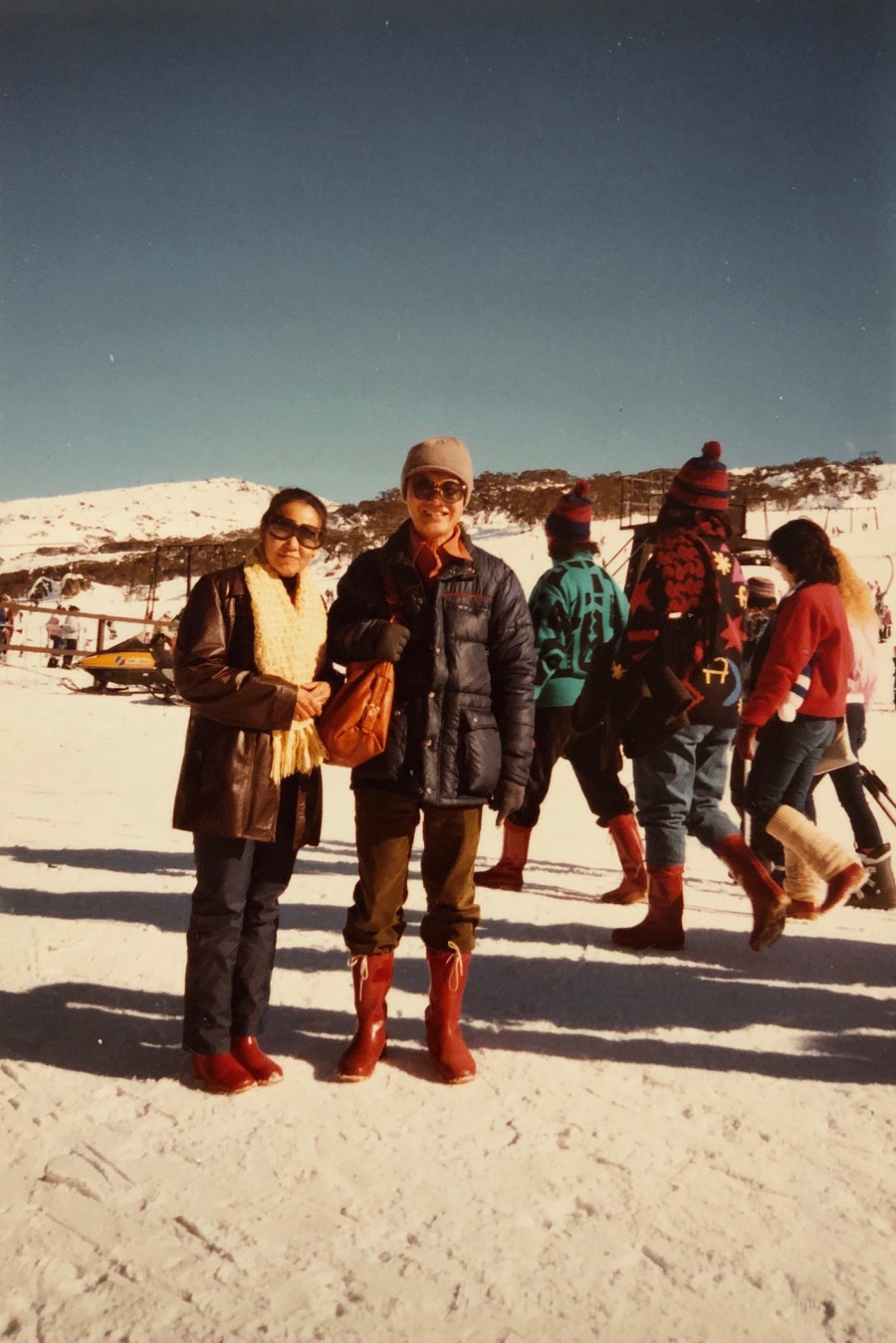

In 1980, when my husband went to China for his sabbatical, I followed and stayed there for three months. That's when I went to look for my ancestors. And you wouldn't believe it. China was so advanced even then. I went to where my grandfather was born. There was a register where all the Chinese in that area had and have their names recorded at birth and at death. The names are all there.

I spoke with someone from my husband's university that was given the role of looking after visiting lecturers. I said to him, "You take me to where this place where I was supposed to come from or rather my grandfather was supposed to come from."

When I visited the place where he came from, I met the locals who explained to me that there were three main streams. Now, these three streams, if your grandfather came from this stream, he would have emigrated to America. If he came from that stream, he would have emigrated to Europe. There's this third stream. He would have emigrated to Southeast Asia. I found that my grandfather was from that stream that had emigrated to Southeast Asia. That's where I found his name in his tombstone. On his gravestone, it has his full Chinese name, where he came from. Everything about him.

As a boy, my Grandfather had moved to Kuala Lumpur. I think he found that in Kuala Lumpur the people were different. They're not like the Chinese. Why? Because the Chinese who emigrated into Southeast Asia partnered with local women and those local women were not Chinese because they mixed, you see.

They mixed with other people who already emigrated before them. Some have made good, others haven't, but the women were not shy. The women from China, once they have already emigrated, they're bold. So if they are not happy in their relationships, they move on and meet someone else. In the old days in Malaysia, it didn’t matter. All right? You know, I've had two children with you. You're not supporting me well enough. I'm not getting on well enough with you, I'll go away. I'll find another man.

The first man my grandmother was in a relationship with produced my father. My grandmother, I thought, "My goodness." Even my own time, I would find it a little bit bold, but she, my grandmother, had three serious partners that she had children with. I remember when I was a child, suddenly I had an uncle appearing and that uncle was from another man and he was the headmaster of a school in Singapore, and he found my father. Somehow they look for one another and suddenly I got a new uncle. My father was so proud of him because he... I don't know who took him on, but he went to school and learned the English language. He then went on to become the headmaster of a school.

Education

When I was seven years old I started my schooling at an all girls Catholic school in Kuala Lumpur by the name of The Convent Of The Holy Infant Jesus. And I think I went to that school because my father managed to get a grant for me to study there. Later on, my brothers attended St John’s which was a boys’ catholic school down the road. I wasn’t a very good student. This is because I never really took exams well. So I would attend this ‘English medium’ school during the day and in the afternoons I would go to a Chinese school, to learn the language. When I was a child I went by the name of Chiew Nya Chit. The teachers at the Chinese school discriminated against me because of my name.

My mother took us to be registered and that headmaster says, "No. She's not Chinese. She's got no Chinese name." Me. "Chiew Nya Chit that's not Chinese. She's not coming in." So mother had to go to a temple and she has a friend who's an abbess. A very well educated, Chinese abbess. Abbess means head of the temple. So she ran this temple, and people would go and pray and give her donations. It was a common thing for unwanted children to be left at the temple. She would then look after these kids.

So the thing is, the abbess gave me a Chinese name - Chiew Pek-Lin. She gave me this name because it points back to an old story of a woman who was very well educated. So my name has even got a history behind it.

The Nuns at the Convent school were horrible. If you were rich they were very good to you. If you weren’t rich, you were considered a nobody. Every week the Reverend Mother would sit on a chair, and there was a bowl in front of her. Everybody walked past and put money in the bowl. And she could see who was or wasn’t putting in. And she was judging.

I used to get in trouble a lot at school. Because of my loud, high pitch voice, I did stand out in a class. When a teacher would come into a noisy classroom, the teacher would locate the source of the loudest student - me. I’d get blamed all the time because my voice is loud and I like talking.

When I was in my teens there was one nun who saw the potential in me. She saw it when nobody did. And she thought that my English was clear. She thought I could be good at acting because when we did drama, she placed me as Jane Eyre. I got the starring role. And when she put up this play, everybody was shocked. I was Jane Eyre. I was shocked, myself. Because, first I was shocked that I was selected to do the main role. And then when I did it, I was shocked that I didn't have any problem. I didn’t know I had it in me. Those who saw it thought that I was a good Jane Eyre.

I had some wonderful friends at the Convent school. To this day, I’m still friends with some of them. One of my closest friends, Ah Fatt, is a woman I became friends with at the convent, after the Japanese left, all those years ago. We were in the same class. She lives in Perth now. We talk often.

The Japanese arrived in Kuala Lumpur in 1940, when I was ten years old. One of the courses of action was to shut down all schools. So I had to stop going to school. My parents organised for me to work with the abbess in the Chinese temple. I went there instead, secretly learning classical Chinese. Classical Chinese is like the old literature. It's very high class. Only the ruling class were using the classical Chinese.

After the war, schools were reopened and I returned to the convent to finish my schooling. Back then the options for a girl were very limited. The only possibilities were typing, shorthand or teaching. That's all.

So after I got my Cambridge School Certificate, I studied typing and Pittman’s style shorthand. Then I got a typing job. I wasn’t earning enough money to help my family and so I applied for a teaching job in a village outside of Kuala Lumpur. Nobody wanted to work outside of Kuala Lumpur due to fear of the communists and the possibility of being brainwashed. I wasn’t worried about that. So I taught English in a Chinese school.

Then there was a boy who worked in the police department and I think he was a bit sweet on me. One day he rode his motorcycle to see me in my village at home and said, "Hey, there's a job going in the police department and if you work for the police, you'd be paid very much more than anywhere else." He said, "You know both Chinese and English, you apply. You will get it." I applied, not because I think I would get it. I applied because the money was very good. It was twice as much as what I was earning from doing both teaching and typing at the same time.

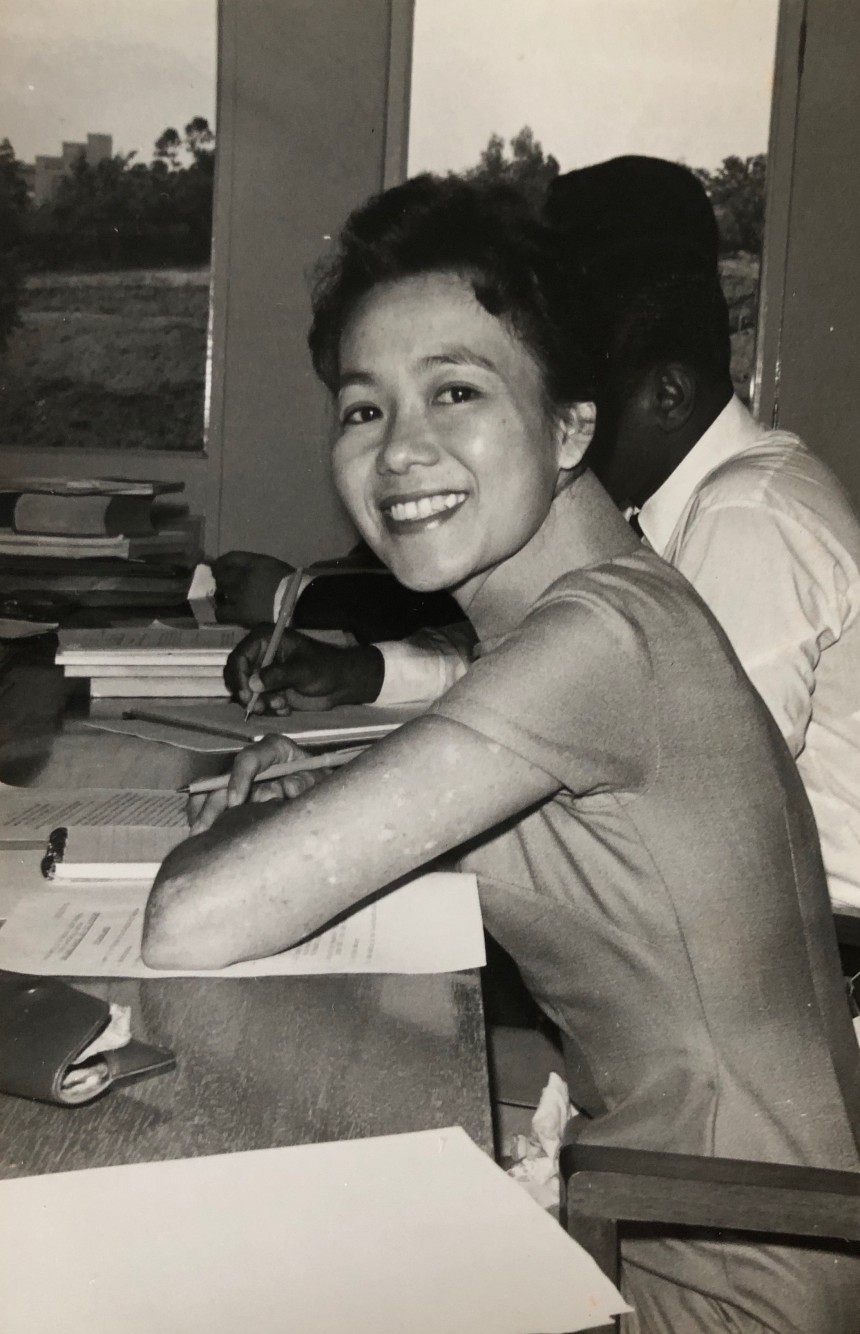

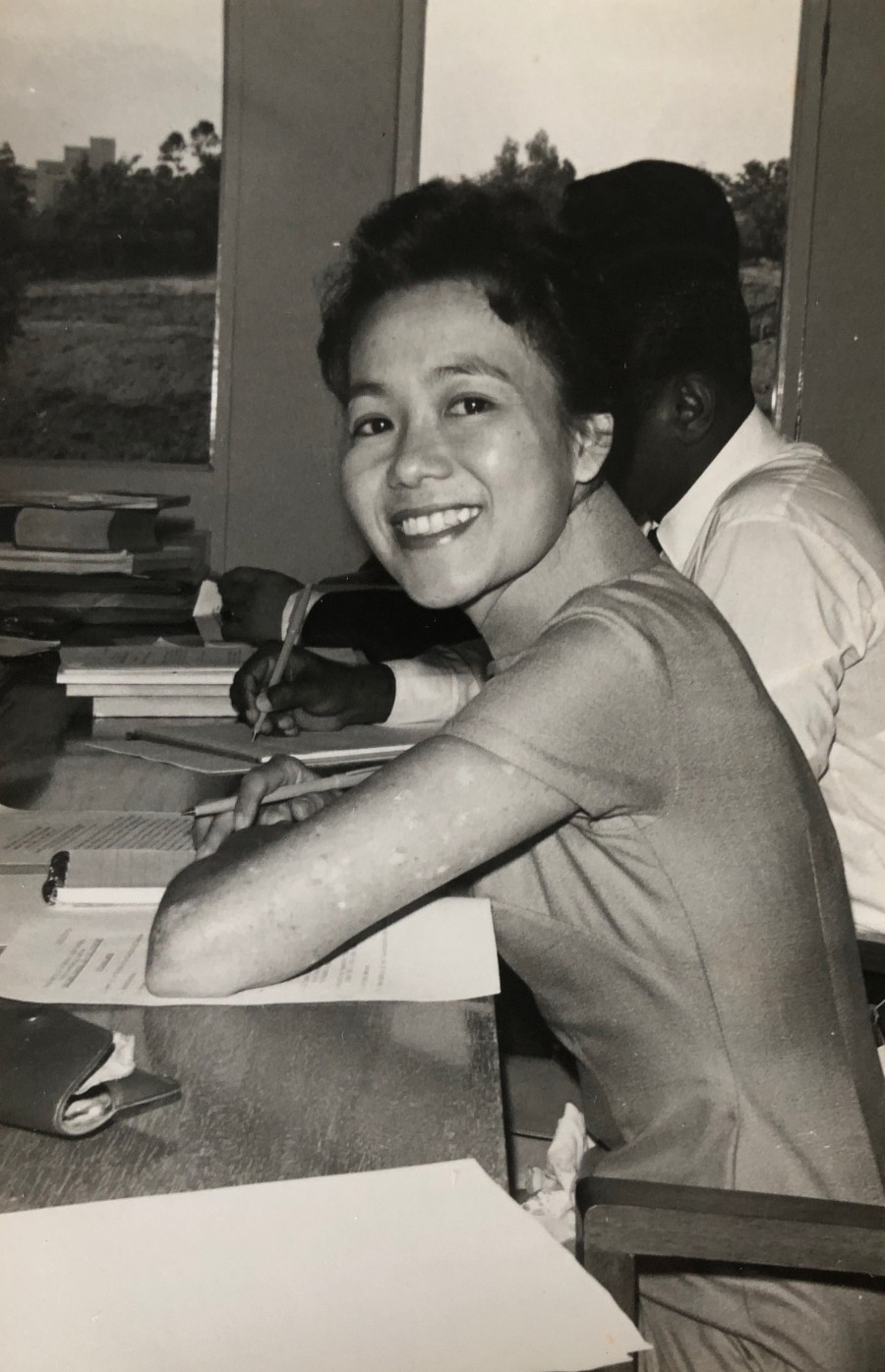

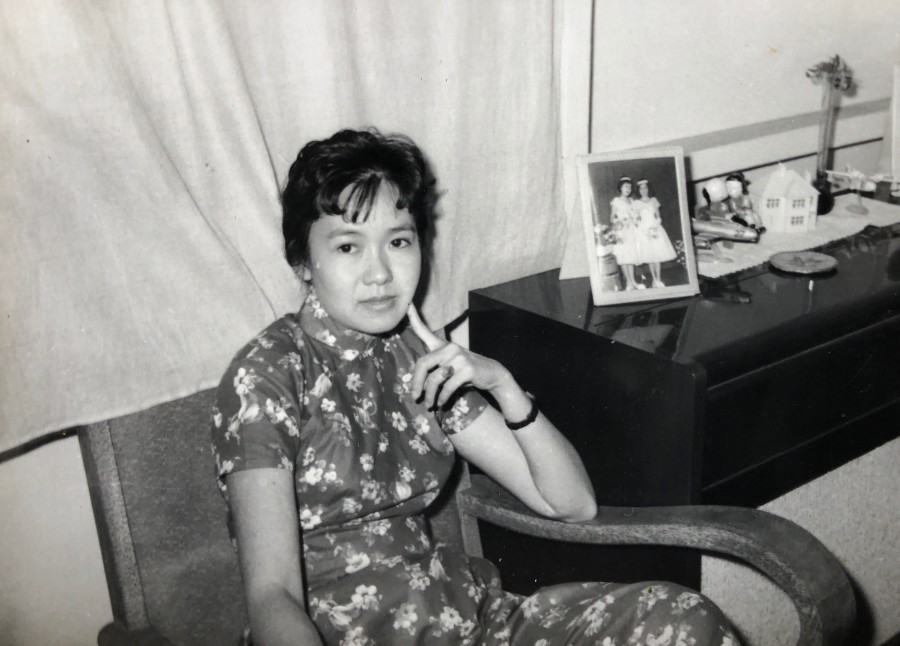

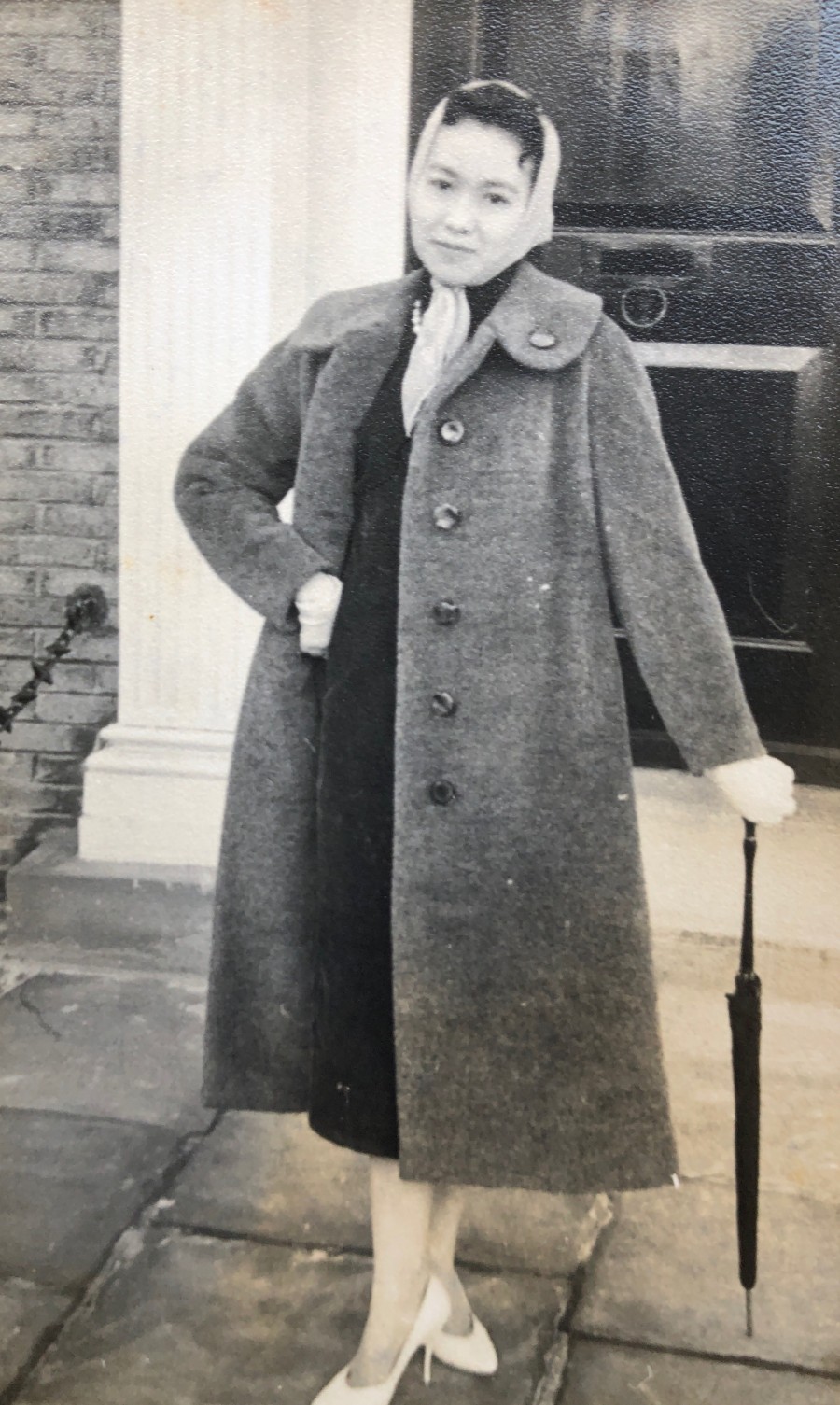

I went for the job and it turned out to be a position working for the secret service. I was successful in getting the job. While working there I met a woman by the name of Joy McGill. She was the secretary of the director of intelligence in Malaya. Later on Joy went back to London but insisted on taking me with her so that I could further my studies and career. This was in about 1953, so I was twenty-three at this point. I studied hard and got A Levels in English.

After that Joy McGill put me through a one year secretarial course at Cripplegate Secretarial College. I was so busy but it didn’t bother me. Joy gave me a collection of Charles Dickens novels and made me read the whole bloody lot.

At this point I wanted to do a degree in Chinese studies. It was a prerequisite to learn yet another language. Joy got me a private tutor to help me to learn French. I got my GCE (A) Level in French in six months.

Years later while living in Australia, I applied to Macquarie University to do a Bachelor of Japanese Studies. I had struggled for a long time with resentment, due to war time experiences. I went to the Macquarie University, I had to see the Head of Department. I said, “Look, I really want to do this degree. The reason is because I want to purge myself of the hatred I have for the Japanese.” She was a Japanese woman. Her name was Zusie Chow.

I did the degree part-time. It was very interesting. I learnt about Japanese literature, history and language. These studies had a very positive impact on me and helped me to heal old wounds. For so long I blamed the Japanese for all the problems I had. I no longer resented the Japanese.

The War

In 1940, during the Second World War the Japanese occupied Malaya. They were very ruthless. They stayed there until 1945. Every crossroad you passed, whether you're riding a bicycle, most of us were riding a bicycle, we had to get off the bicycle and we had to push our bicycle past a sentry, who is a Japanese chap. We had to bow our head as low as we can, because he represents the Emperor. My father was slapped many times by these sentries because he's a short little man. He couldn’t bow low enough, and so he was beaten. That's one thing. Or what you should see is when you go in the crossroad in Kuala Lumpur, you see the heads of people you know, hanging there for everybody to see. They were ruthless. I was in my teens at this point. I was forced to go and work for them. I don't know why they wanted steel wires to be rolled up. And they would say, ”You sing a Japanese song!” I didn’t know any Japanese songs. And so if I didn't sing it well, I’d get slapped by them.

The Japanese seized houses they wanted and more seriously than that, they took women whenever they pleased. Because they didn’t bring Japanese women with them to Malaysia, the soldiers would go to houses and look for ‘Kunyan’ (women). One day the Japanese came to our house. I was twelve years old at the time. In those days the bathrooms had big tanks of water because we couldn’t waste water. My mother and I hid in our water tank. We kept our heads under the water, not breathing so that there were no bubbles. Luckily they didn’t find us. I was too young to be terrified. My mother must have been. All my mother did was push my head down so that I didn’t resurface to breathe. This remained a big fear for me but in my case, at that time, I was small and I didn’t look my age. I looked younger. Quite a number of my friends weren’t so lucky.

Many years later when I was living in Australia I did a degree in Japanese Studies. I went out to Macquarie University and met with a Japanese woman who was the head of admissions. Her name was Zusie Chow. She married a Chinese man. I told her the reason that I wanted to do the degree was to purge my system of the hatred I’d been holding onto for the Japanese since the war. She said, “Yes, I give it to you.”

I said, “Don't give it to me if there's no place because it's not fair.”

I did the degree. I studied part-time over several years. The course looked at Japanese history, language and literature. Doing the degree was very helpful and helped me in the way that I hoped it would. One of my best friends who lives in Osaka, communicates with me. Not in Japanese. But no more hatred of the Japanese. Because I blamed them for all the problems I had.

The Secret Service

After I finished school and had completed some study to learn typing and shorthand I secured a typing job. This didn’t pay very well and so I started teaching English at a Chinese school in a village outside of Kuala Lumpur.

I knew a boy who worked in the police department. I think he was a bit sweet on me. He told me about a job going in the police department. He felt that with Chinese and English language skills, I’d have a good chance of getting the position. The money was very good, paying almost twice as much as what I was earning for both the jobs I was currently doing.

When I was interviewed, I wasn't even interviewed in an office. I was interviewed out in the open with two tall white men and two communist Chinese men. At the start of the interview it became apparent that this wasn’t for a job within the police force - this was for a position with the secret service. The white men spoke to me in English and the Chinese men spoke to me in Chinese to see whether I was up to scratch or not.

For a long time I couldn’t talk about the work I did there. In fact, I tried to wipe it out of my mind. Even now I don’t even want to talk about it. It was quite confronting. It involved staying in the prison. I heard and I saw awful things.

While I was there, I met a woman who was to become a very important and influential person in my life. Her name was Joy McGill. She was an English woman who worked as the secretary of the Director of Intelligence in Malaya. Joy often needed me to translate and speak Chinese. It was through doing this for her that I rose.

Joy’s husband was a major in the military. When he finished his assignment in Malaya, he and Joy had to return to England. Joy came to me and said, "I'm not leaving you behind. You're coming back with me."

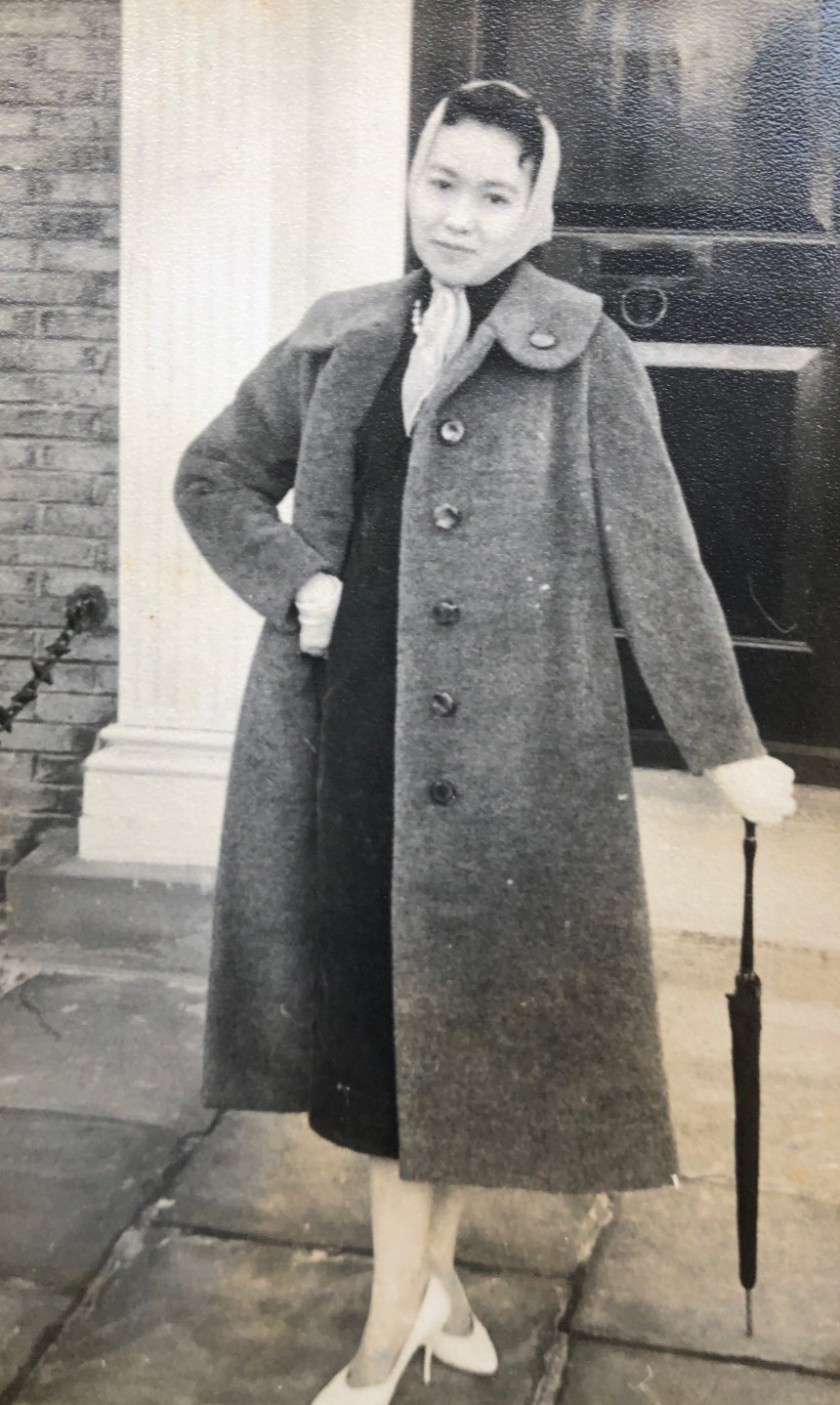

London

During my time working for the Secret Service, Joy and I had become good friends. She just took on a liking to me. I think it's because I'm straightforward. You see, when I talk, I don't hold back. I don't have all this, what do you call it? Looking up to the whites or looking down. Everybody is equal. I was raised this way. And I think she appreciated that. So Joy was always very encouraging and eager to help me further my education. She bought me this whole set of Charles Dickens Novels and she said, "I want you to read through." And all my vocabulary came from there. When Joy’s husband’s assignment in the military came to an end, they prepared to return to England. Joy came to me and she said, "I'm not leaving you behind. You're coming back home with me." And that's where I got my break.

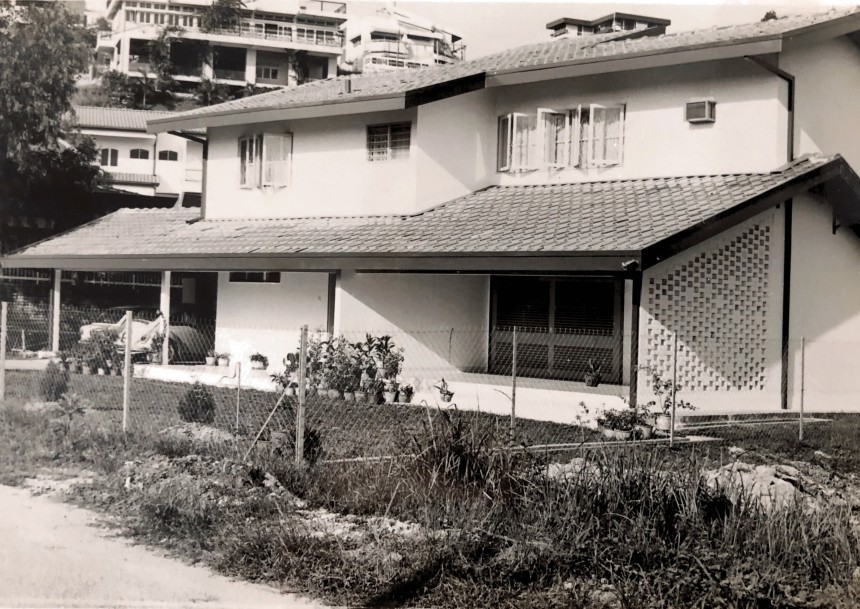

I was worried about my family as I was helping support them with my income. At the time I had a very rich boyfriend. He said, “I will look after you and look after them.” Knowing then that my family would not be able to manage without me there I happily agreed to go. My boyfriend couldn't leave me alone, but he provided me with lots of money for the entire time I was in London and I was able to help my family out. In fact, he bought a house for my family in Kuala Lumpur to live in. This man was my first serious boyfriend, although I didn’t care for him all that much. At this stage in my life I didn’t know what love was, in that way. I was very grateful to him for supporting my family and me. In doing this I think he thought that he was securing a future together with me. I didn’t feel the same way and so we never married.

When I arrived in London, the first place I stayed at and lived in was at a YWCA. I shared a room with this Irish girl, her name is Beatrice. I called her "B". We were on the fourth floor. And there was a swimming pool at the bottom. And I have always been a cheeky person. I've never changed, poor or rich. We were playing around one day and I’m not sure exactly what I said but I teased her. She took great offense at what I said. The windows were wide open. She said, "You say it again, I'll pull your arm and throw you out that window." So I thought to myself, "This is losing face. How can I not say it?" And then I was saying to myself, "No, she can pull me, she can pick me up and throw me down." So we were sitting opposite each other. "Say it again. You're going to get it," she told me. I said it again. She was coming up to pick me up, to throw. So I had to think. I actually gave myself full marks. Before she could reach me, I jumped onto her and tickled her. Then I said, "Say sorry. I won't stop tickling you until you say sorry."

Sometimes I think of this because to me at that time I surprised myself. I realised that under pressure and in the face of what was going to be a serious confrontation I could come up with something to diffuse the situation. I could think very quickly when I needed to.

Anyway, B and I became good friends. She was an Irish national swimmer, training for the Olympics. We stayed friends for a long time. She even took me to Dublin to meet her family. We were very close.

Later on, I got a very good job, given by the Malaysian government. I asked B to come and stay with me at my new flat in Maida Vale. It was quite a good area. While I was living in London, I got to know this group of doctors. Some of them were married. Even though they were all a bit older than I was, we got along quite well. They seemed to appreciate my straightforwardness. It was through my doctor friends that I was introduced to quite a number of what you may call upper-class people. The class system in England means that its people can be very very discriminating. But I never really let that bother me or influence who I became friends with. So in the case of my doctor friends, I didn’t feel inferior to them, because you see, Joy had taken me on. Wherever she went for weekends, she’d take me with her. So I met some very interesting people.

My job with the Malaysian government involved placing Malaysian and Singaporean students into good universities in London. And when the office couldn't succeed, they would say "You go. You'll be able to put him or her." And I invariably could.The thing is this, I think my own estimate of myself is I'm small, and I talk loud, and I'm not bad looking, and when I go meet these people, I'm not worried about them. I talk to them as equals and as a friend. I don't know how I cultivated that confidence. And so I never really failed. I would go to Cambridge, I would go to Oxford, and I would persuade the person in charge of admissions to take on students. I’d say, "This is a good candidate. If I were you, I'd ask her or him to come over for an interview and see whether you think he's good enough for the course or not." I gave them ideas.

Then I earned an English Degree. For some reason, in order to do the degree, one had to gain their ‘A Levels’ in English. So I did that too. I think language is in my system. I am grateful for that. I studied the greats, reading Chaucer and Charles Shelley, among others.

While I was doing this, Joy put me through secretarial college. The college was called Cripplegate Secretarial College and I studied there for a year.

I decided then that I wanted to do a degree in Chinese Studies. I discovered that in order to do this I needed to pick up another language. I chose French. Then Joy said, look, I'm getting you a private teacher to teach you. In six months I got my GCEA level in French.

Teaching

When I finished school, I went to teach English in a Chinese Medium school. It was well known that this village was heavily occupied by the Chinese Communists. Nobody else wanted to work there, due to fear of brainwashing. But I wasn’t worried about that. I was there to teach and make money to support my family and so I wasn’t concerned about communists.

A few years later, when I first arrived back from London, I got a job at a boys’ secondary school, named the Victoria Institution (VI). At this point I wasn’t a fully qualified teacher. I needed to get my Teacher Training Certificate. So I went back to London to get my teaching degree there.

After I completed my degree I returned to Malaysia. I asked to be posted to the boys’ English College in Johor Bahru. I taught there for a couple of years.

After this, I went to work for the Ministry of Education in Malaysia, as a supervisor in the region of secondary schools. Paul Chang, a man I knew while studying in London, worked for the Ministry. He thought I’d do well in administration for the Ministry of Education and so he invited me to come and apply for a position there. Paul was quite influential in my professional life.

After some time working at the Ministry of Education, I was sent to be the Headmistress of a large girls’ school in Kuala Lumpur. The previous headmistress was apparently demoted due to her inability to get along with her teaching staff.

This school didn’t have a name. It was known by the title, ‘Section 14 Secondary School.’ I didn’t like the idea that the school didn’t have a name. So I named it, Sri Aman. When I took over as Headmistress of the school, people didn’t think very much of it and so it wasn’t a very popular institution. Slowly, the people who lived in the area developed confidence in the school and our attendances rose. I was Headmistress of the school for about five years. I felt that in my way of working there, I had a method in my madness. Whatever decisions I made, I always explained to the teachers why. And our student results improved enormously. This was a very good time of my life. I felt a real sense of success during this time.

When Francis, Li-Chuen and I left to emigrate to Sydney, Australia, the students surprised me. They hired three buses to see me off at the airport. The whole school was there. It was very emotional. I didn’t think the girls at the school really liked me. I wasn’t overly strict but just worried that maybe I hadn’t really gelled with them. Seeing the whole school waving us off at the airport changed that and I realised I had developed meaningful relationships with the staff and students at Sri Aman.

Soon after arriving in Sydney I started doing some casual teaching work but I hated it. I felt like I was just being paid to babysit. It was so different from regular teaching.

I decided I wanted to teach Chinese and so I took a position at The School of Community Languages. The lessons were taught on a Saturday. The government wasn’t offering language courses in a lot of High Schools at the time. If you wanted to study a language for your Higher School Certificate, you would have to go to a language school on a Saturday. I really enjoyed teaching there. The students were all year 11 and 12 students and so they really wanted to learn and to do well. I taught there for ten years.

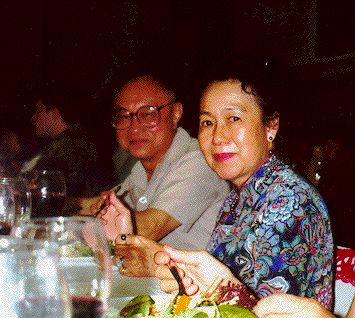

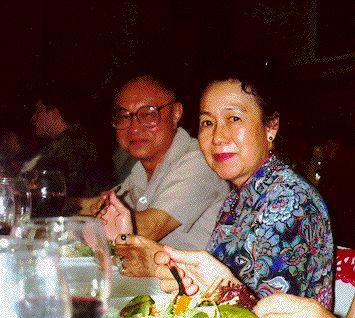

Francis Wong

My Husband, Francis Hoy-Kee Wong, was baptised on the 22nd of October, 1926. As a little baby he was taken on by a woman who was acting on behalf of her parents. This old couple really wanted a son to keep the Wong name going. So they raised him. They called him their grandson but they raised him. Their daughter, who accepted Francis, already had several daughters. So they hoped that he would carry the name and bring in Wong boys. And poor thing, he just produced a Wong girl. I think my daughter, Li-Chuen Wong knows the story about Francis’ adoptive parents wanting the Wong name to continue and so all of her children have the Wong name in their names on their birth certificates. I’m touched that Li-Chuen has kept her father’s surname and she is always known as Li-Chuen Wong.

Years later his grandparents, who raised him, died. Lucy, felt that all the money should go to her, because she was the biological daughter. But Francis’ grandparents had other plans. They felt that because they had adopted Francis, he was as good as their son and he should, therefore, receive an inheritance. They were quite well off. They had several rubber plantation estates . So some of the property went to Francis when they died. Prior to their passing, Lucy had been in charge of all her parents’ money. Her parents told her explicitly, that specific estates were to go to Francis. And so he received a couple of houses. On a side note, strangely, because she didn’t give birth to any boys, years later, Lucy too, adopted a boy, this time treating him as her son.

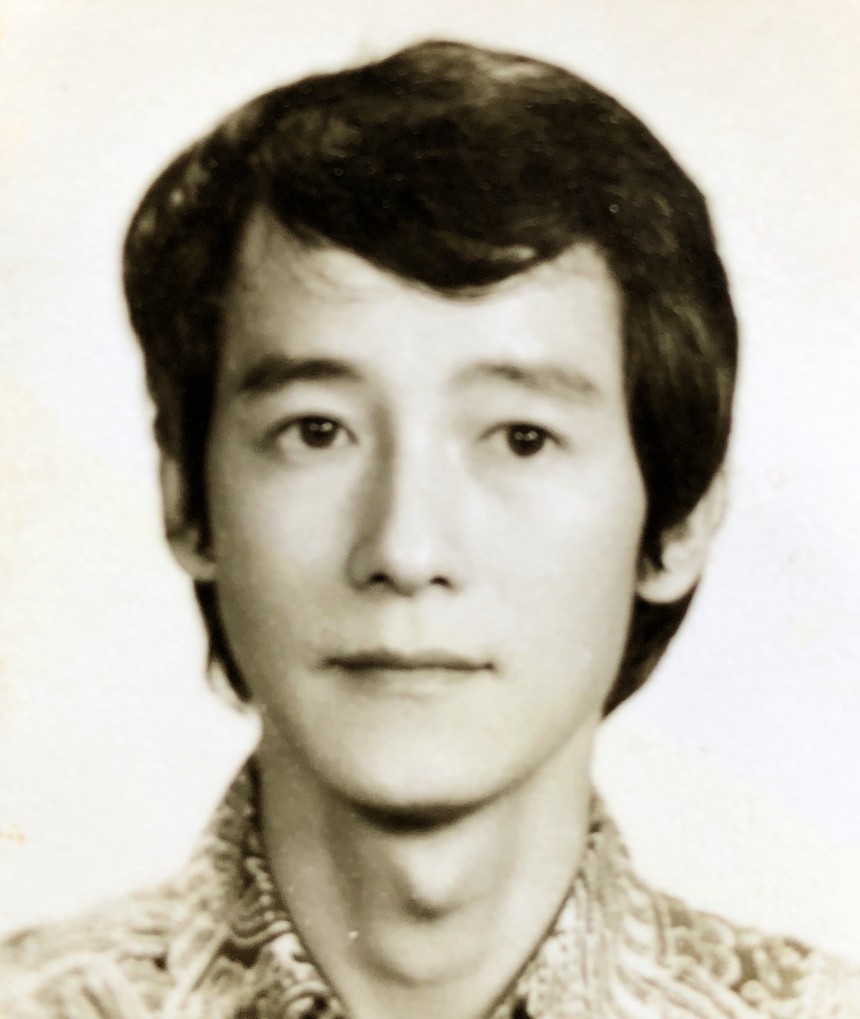

Throughout his childhood there was no love with his adoptive family. So in his loneliness and search for meaning, he turned to the brotherhood - a new family. He joined the De La Salle brotherhood when he was fifteen or sixteen. As a brother he was called Brother Brazilian. Belonging to a brotherhood, Francis had to take the three vows of chastity, poverty and obedience.

Francis was given the job of being the Headmaster of 'The St John's Institution', an all boys' school in Kuala Lumpur. This is the same school that my brothers went to years earlier. He didn’t want to do the job. But following the vow of obedience meant doing whatever you were told. He didn’t enjoy the job and struggled with the administration that was involved. In the end he decided to leave both the job and the brotherhood.

In order to leave the brotherhood, he had to have approval from the Pope. By then, Francis had already known me. I was working for the Ministry of Education, which involved looking after all of the secondary schools in the area, including St. John’s. He would phone me and we would talk about matters relating to his school. Over time he opened up to me about things he was struggling with in the brotherhood. So he would be phoning me and phoning me and phoning me and asking me what to do, what to do. Until one day, with Rome finally giving him permission, he left the brotherhood.

Outside the brotherhood, I was his closest friend. The moment he left, two others followed. Two other brothers followed him.

Leaving the De La Salle Brothers left him feeling lost. He’d been there since he was a teenager and so he really was starting over. Fortunately, thanks to his inheritance from his grandparents, he had some financial security behind him.

The De La Salle Brothers had housed him and fed him. So here he was at about the age of forty-three. Every day he'd be phoning me asking, “What should I do? And then he got, I don't know from where, my home number. So we would talk often on the phone. One day I got so fed up with him. I said, “Why are you ringing me? Day and night you are phoning me.”

He said, “You’re the only person I know who can tell me what to do.”

“Then Marry me,” I said. “Do you want to marry me?”

“Okay."

Then I said, “Are you really serious?”

And he says, I might as well.”

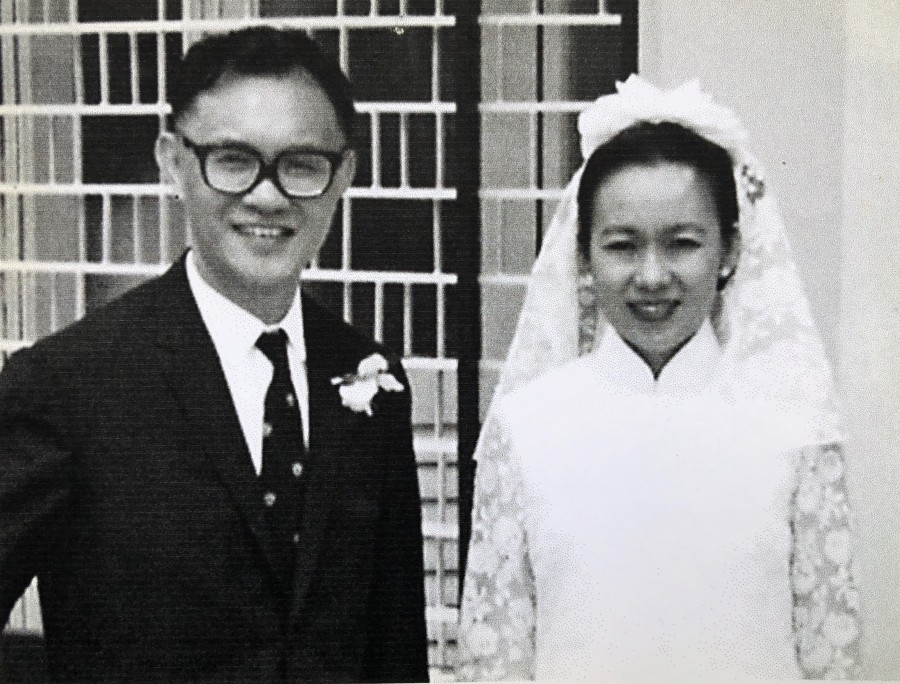

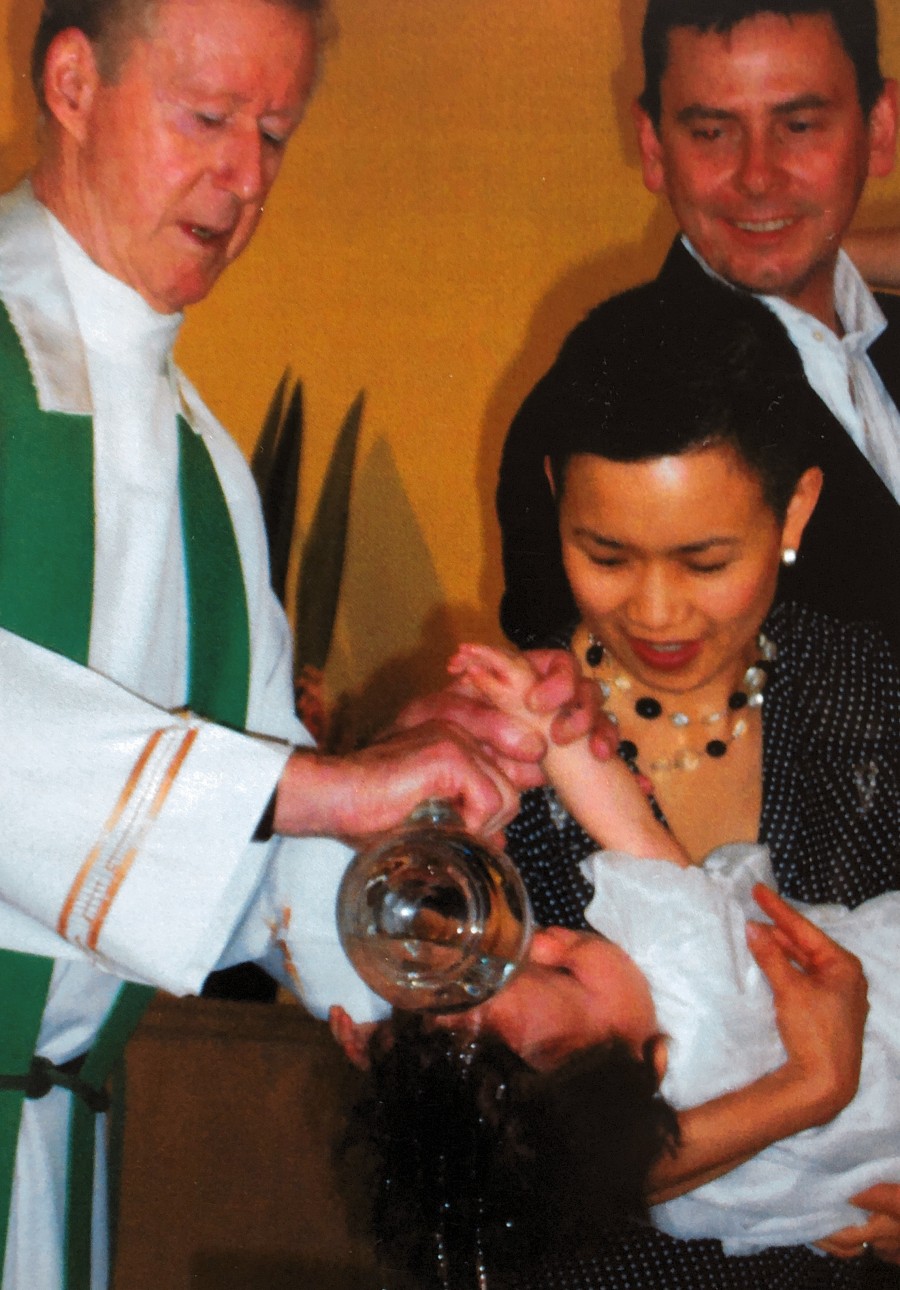

Francis found a priest and we got married in a Catholic Church in Kuala Lumpur on the 19th of December, 1969.

I was still working for the Ministry. Some of his former colleagues said that I enticed him to leave. So you know me, I've got such a thick skin. I said, "Who cares what you think?"

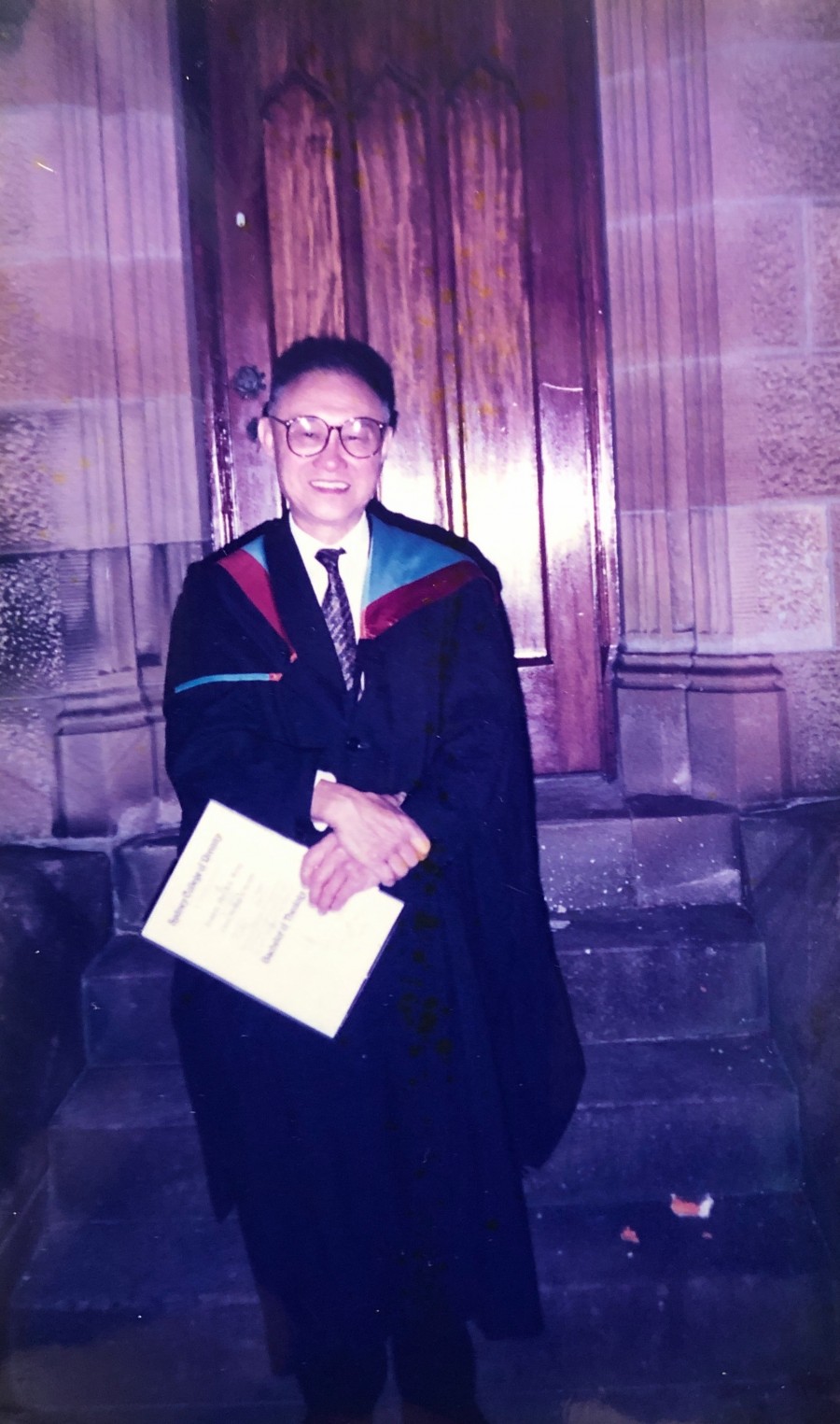

Once we were married, because Francis was brave enough to leave the brotherhood, he got a job straight away as a Senior Lecturer at the University of Kuala Lumpur. At this point he had written three books on comparative education. He was actually very proud of these books. He spent a lot of time researching for each one. Working at the University gave him a lot of satisfaction. It was the job that he had wanted to do for years. He didn’t want to continue on working in administration. He didn’t know how. At this point he has obtained a PhD in Comparative Education.

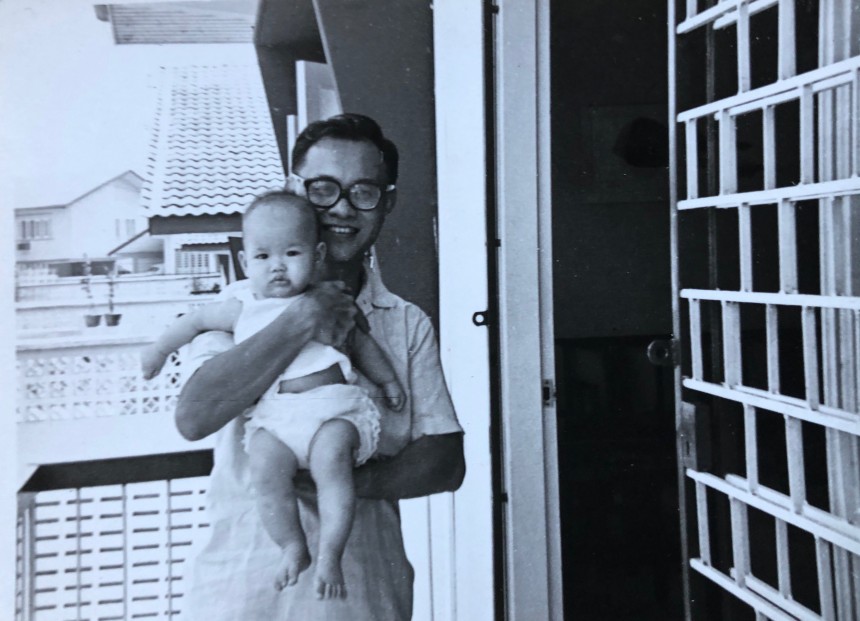

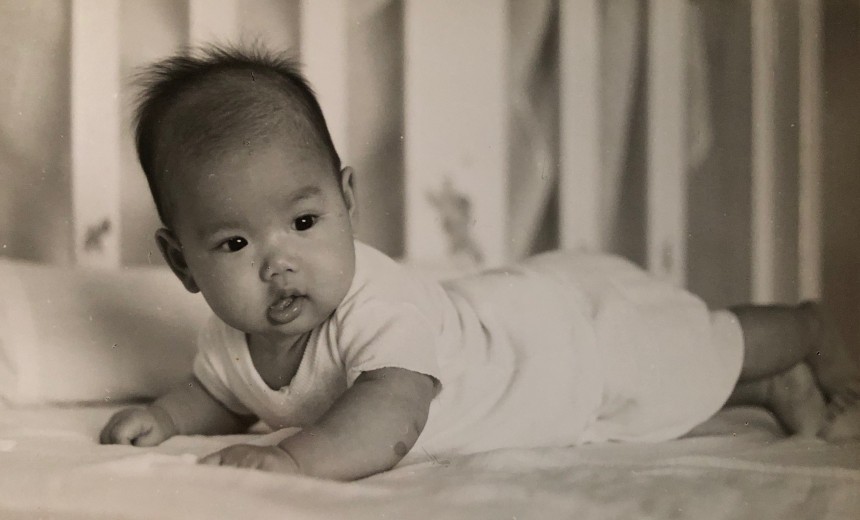

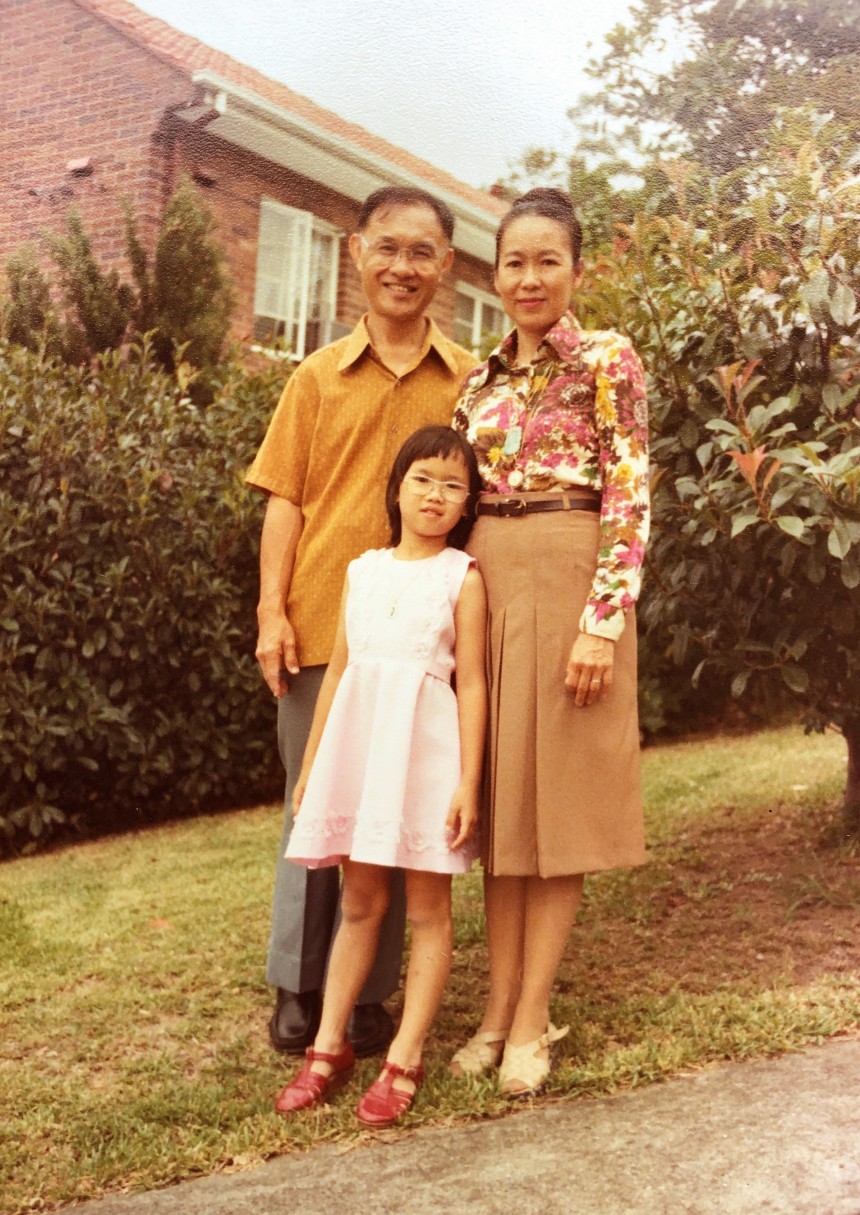

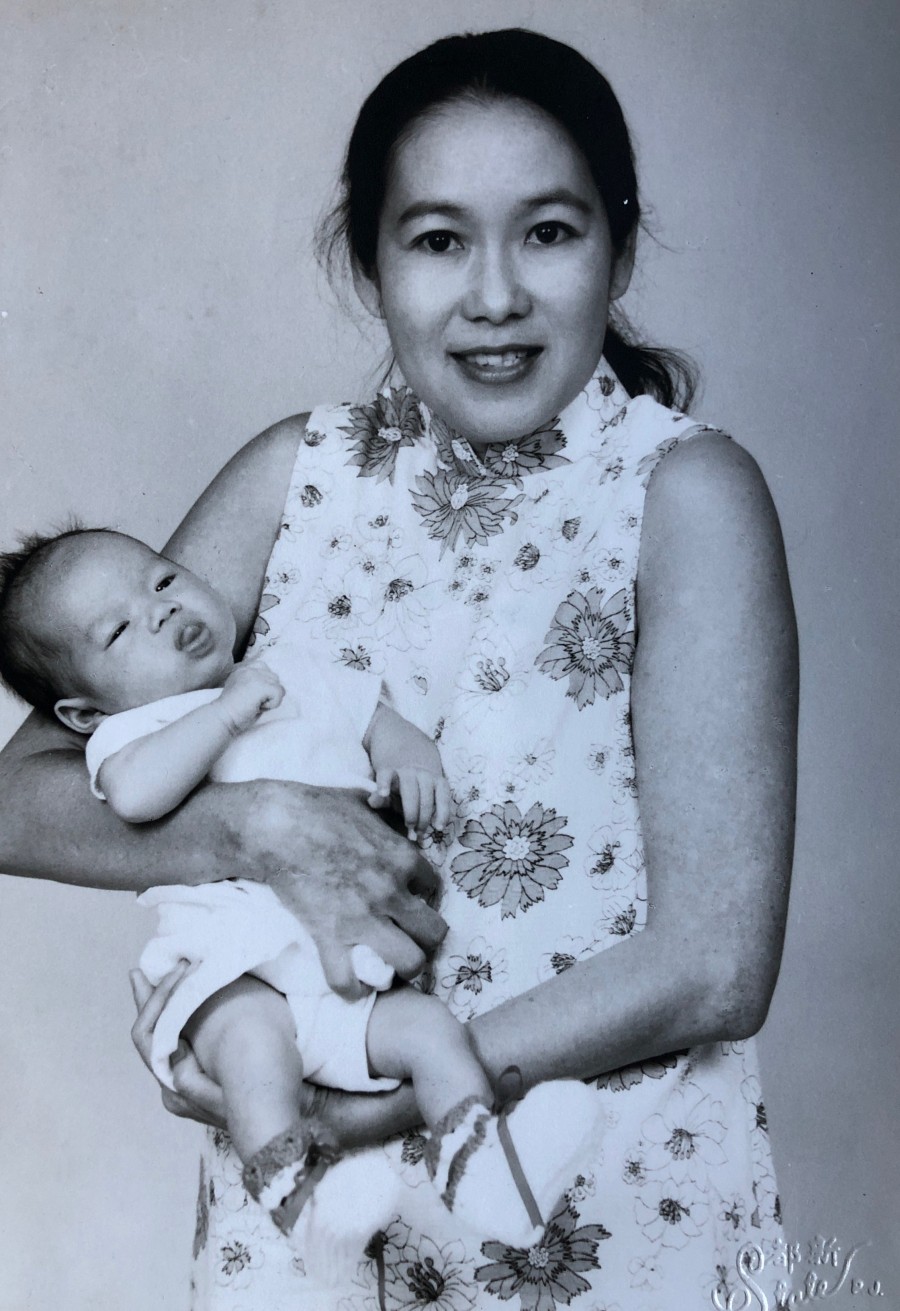

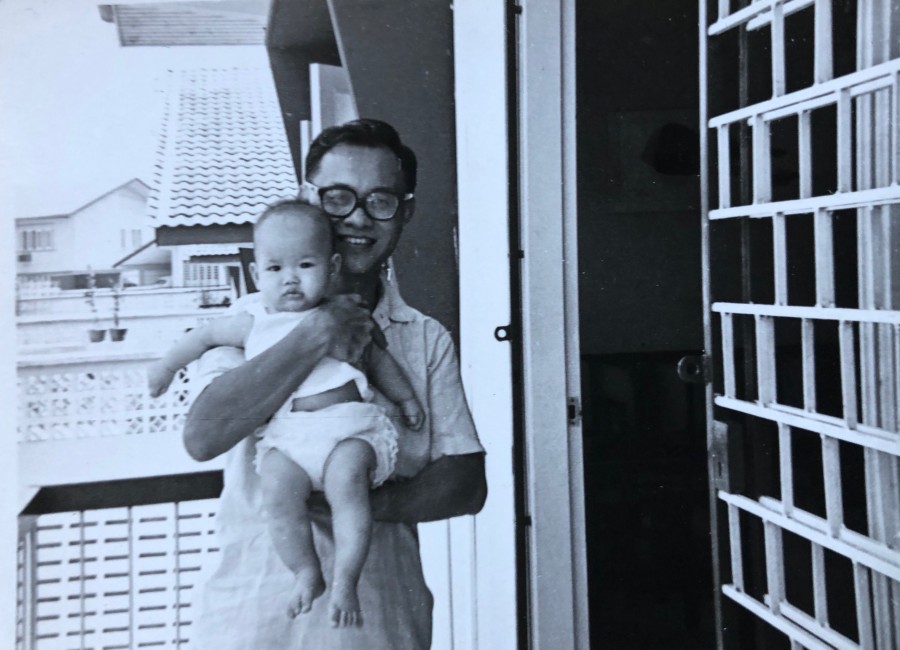

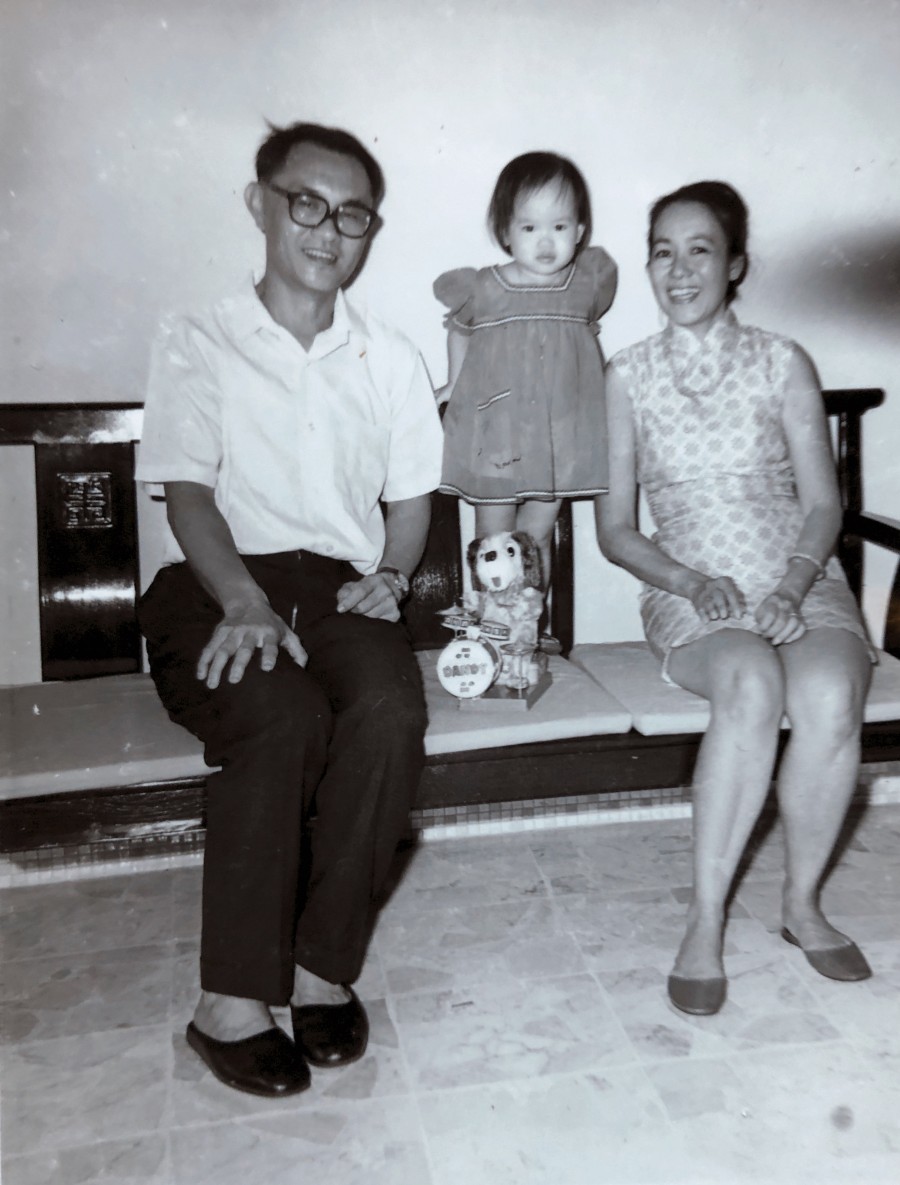

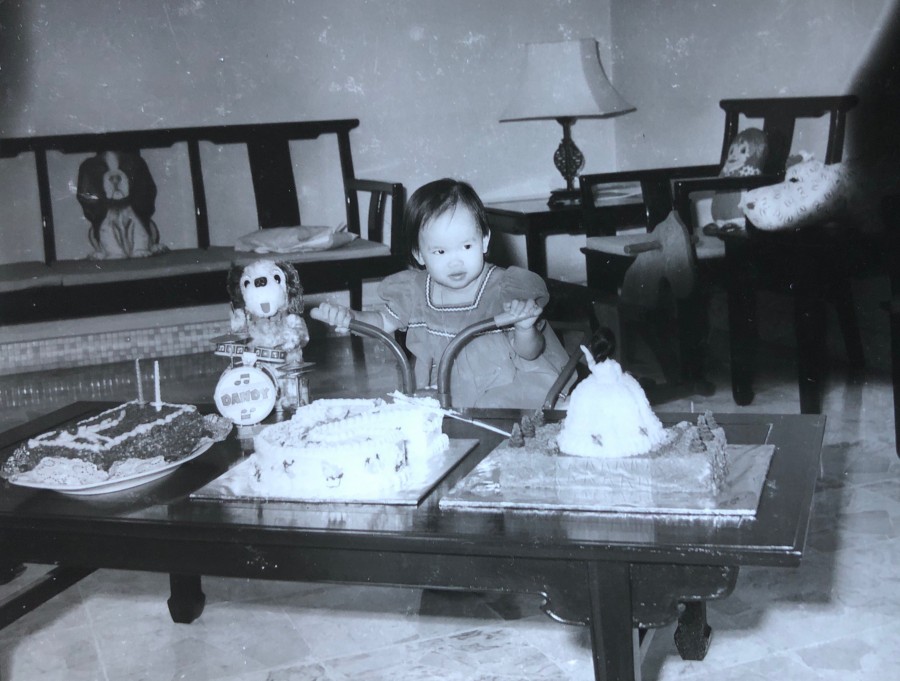

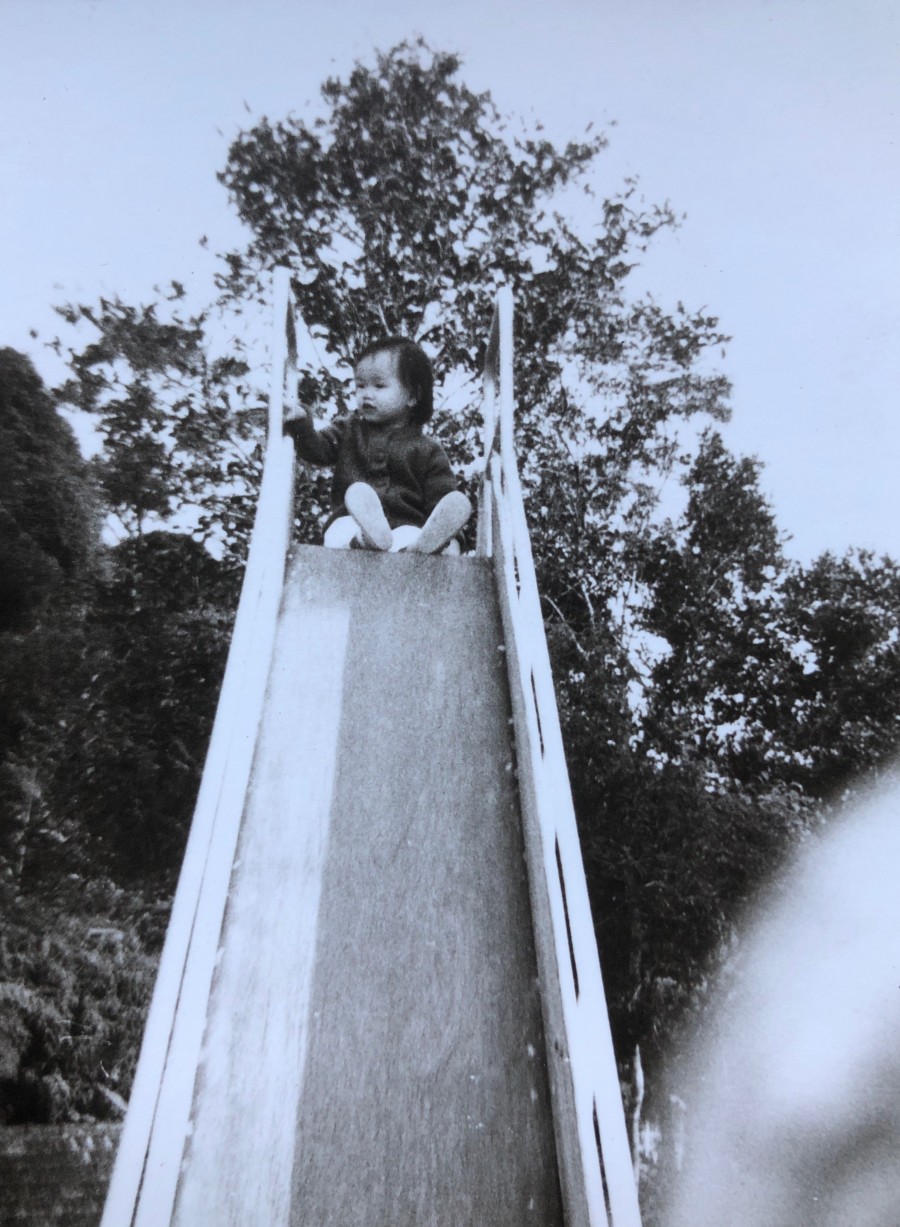

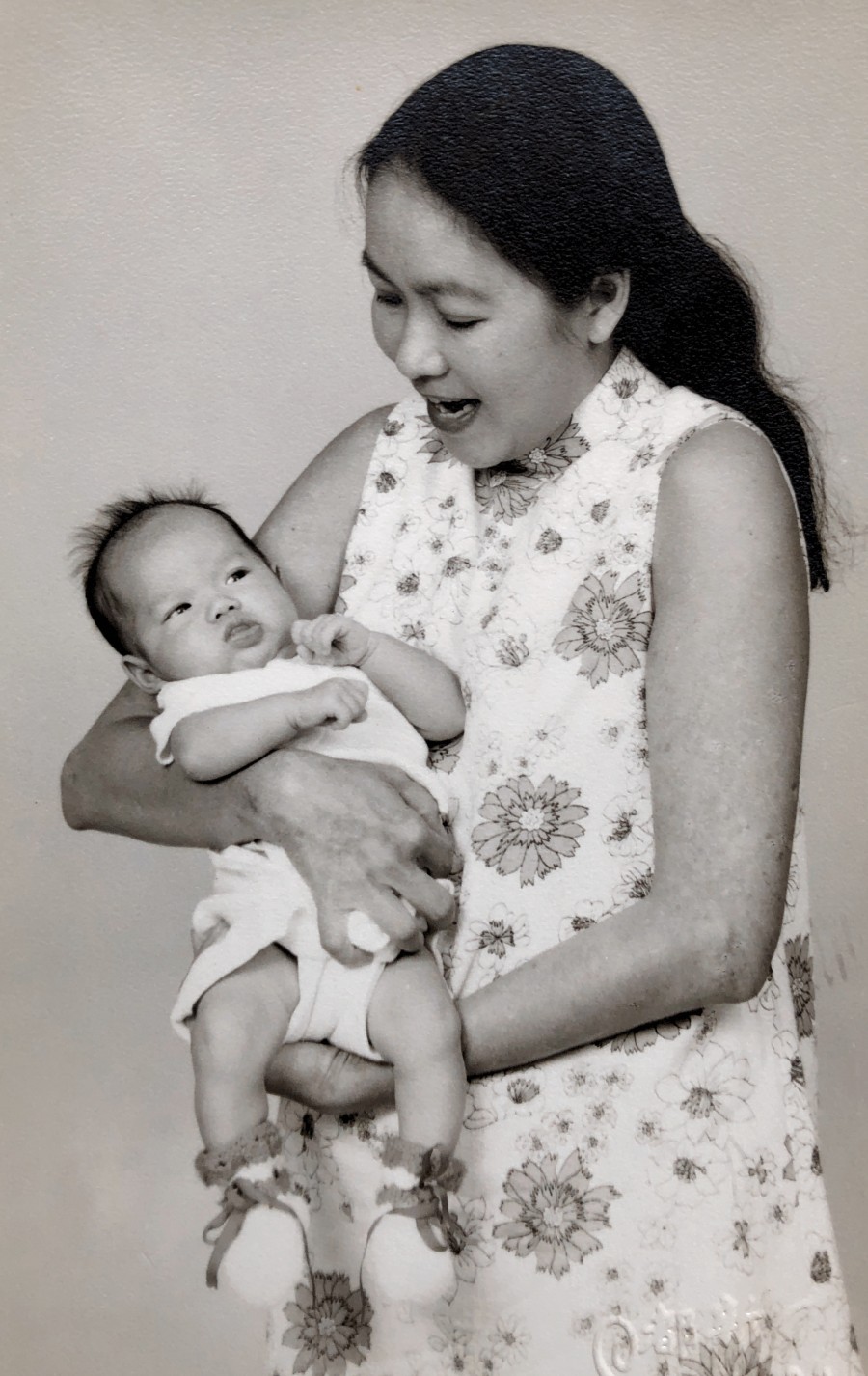

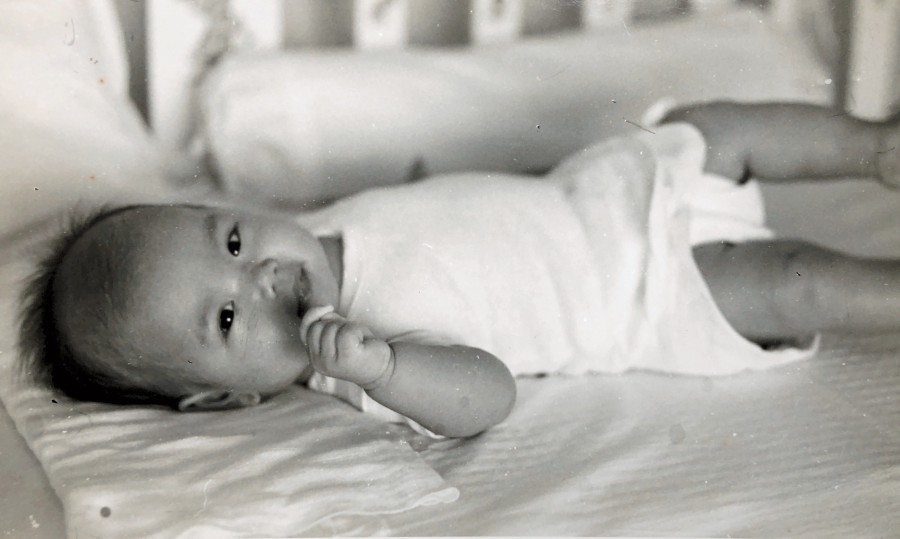

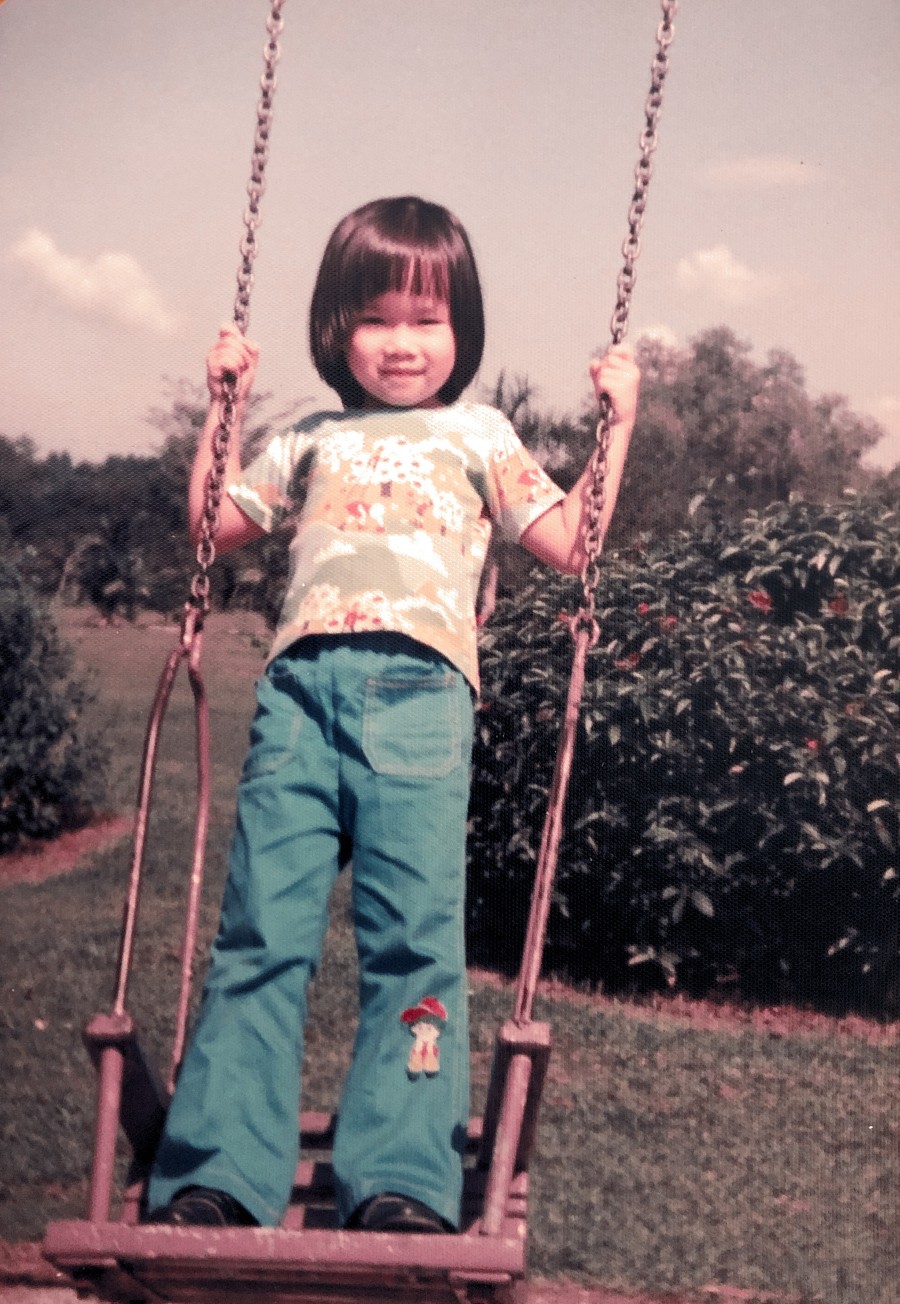

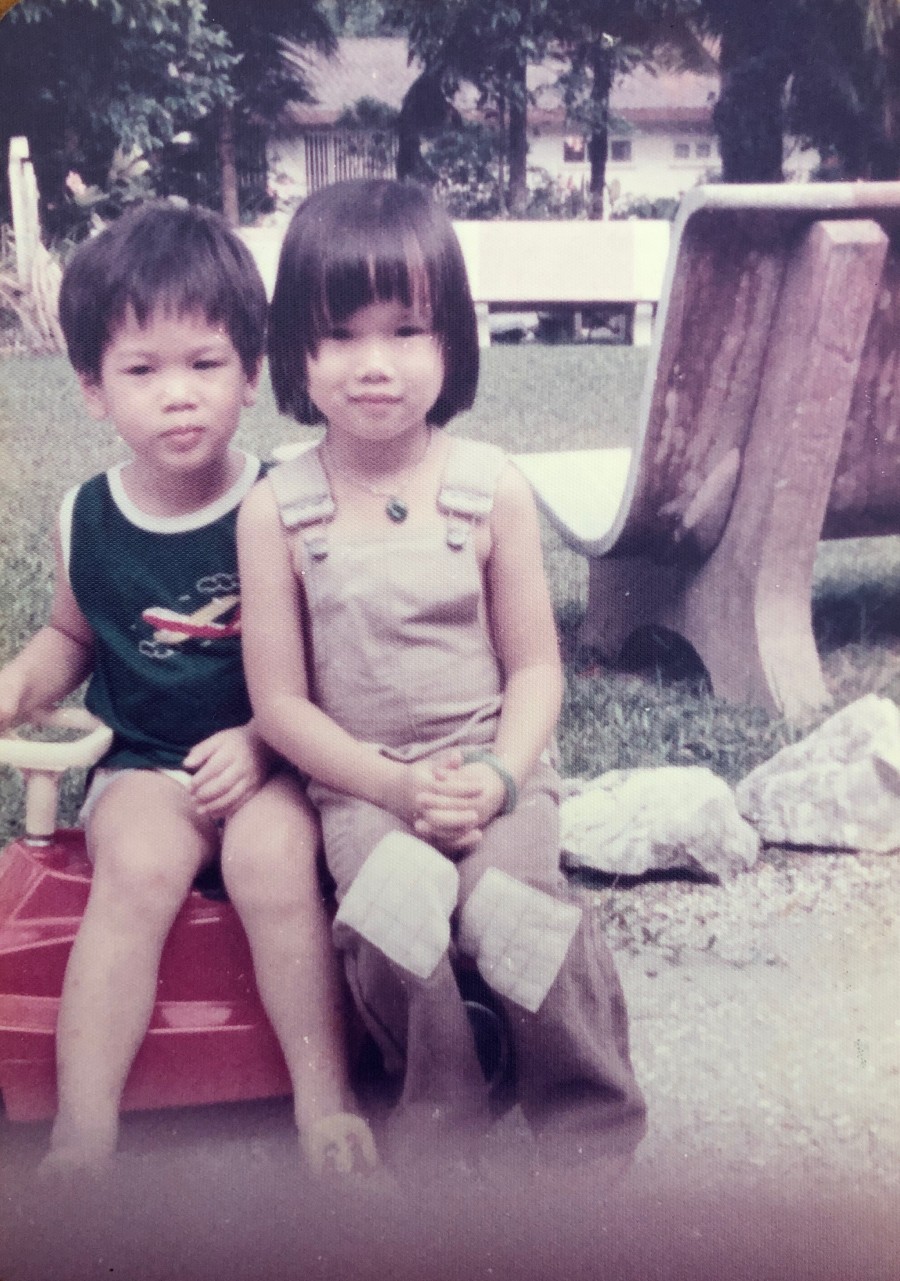

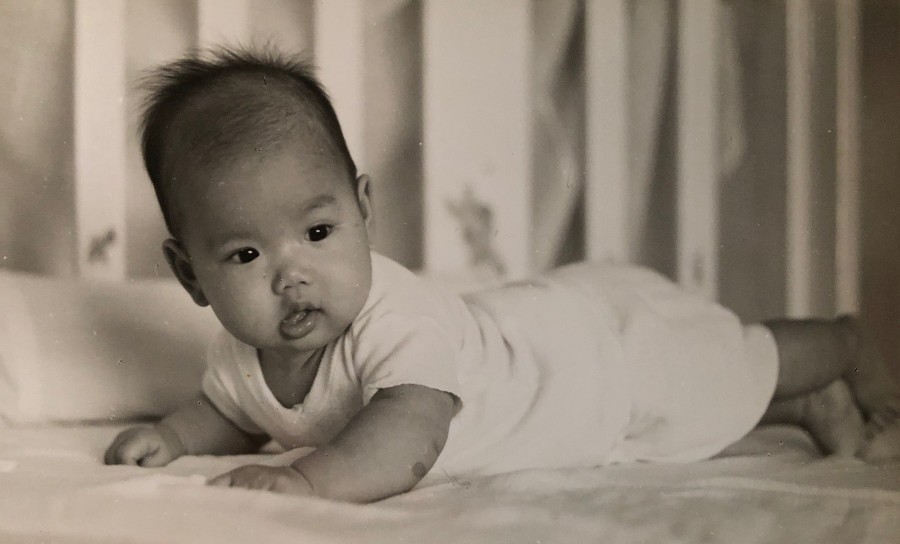

Two years later, on the 26th of August our little girl, Li-Chuen Wong was born.

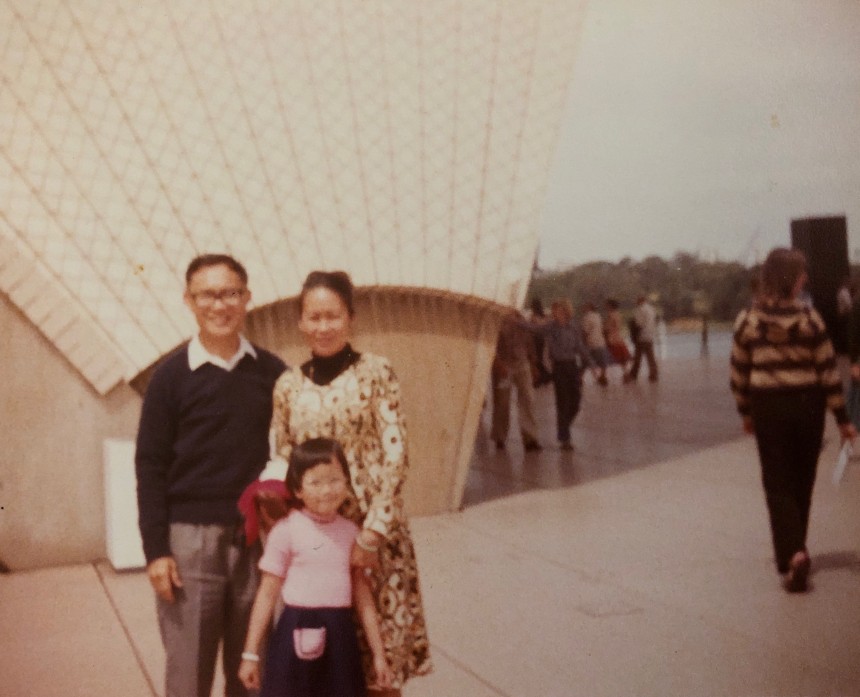

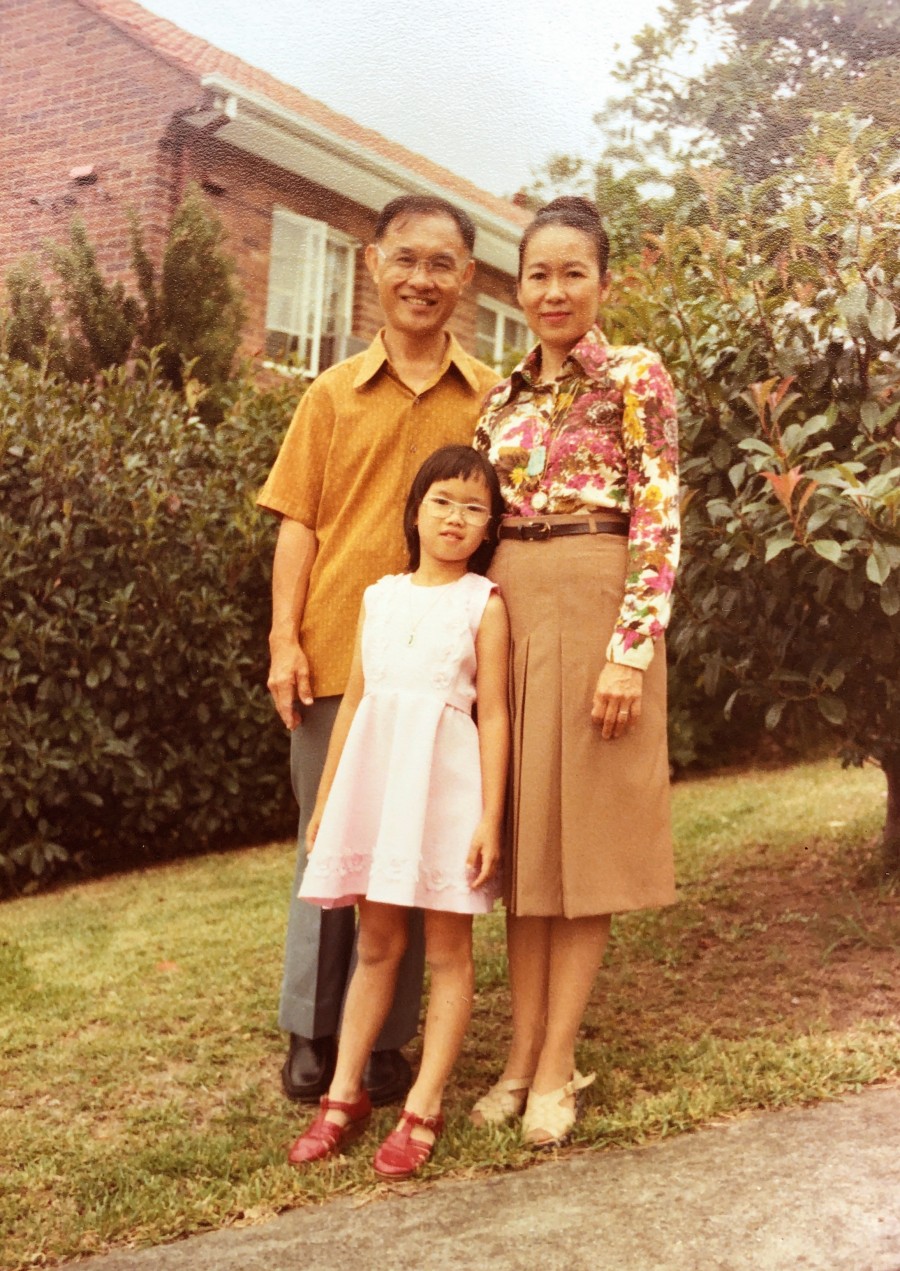

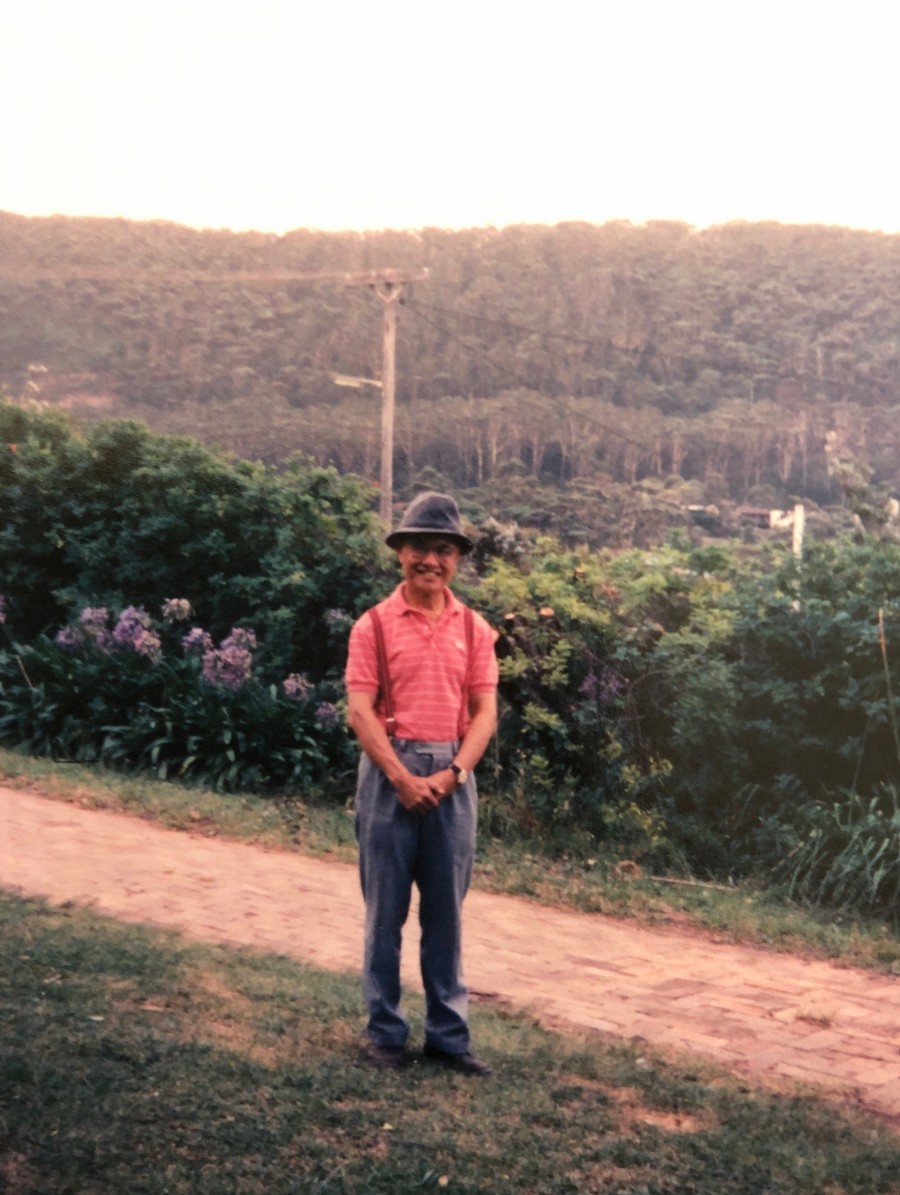

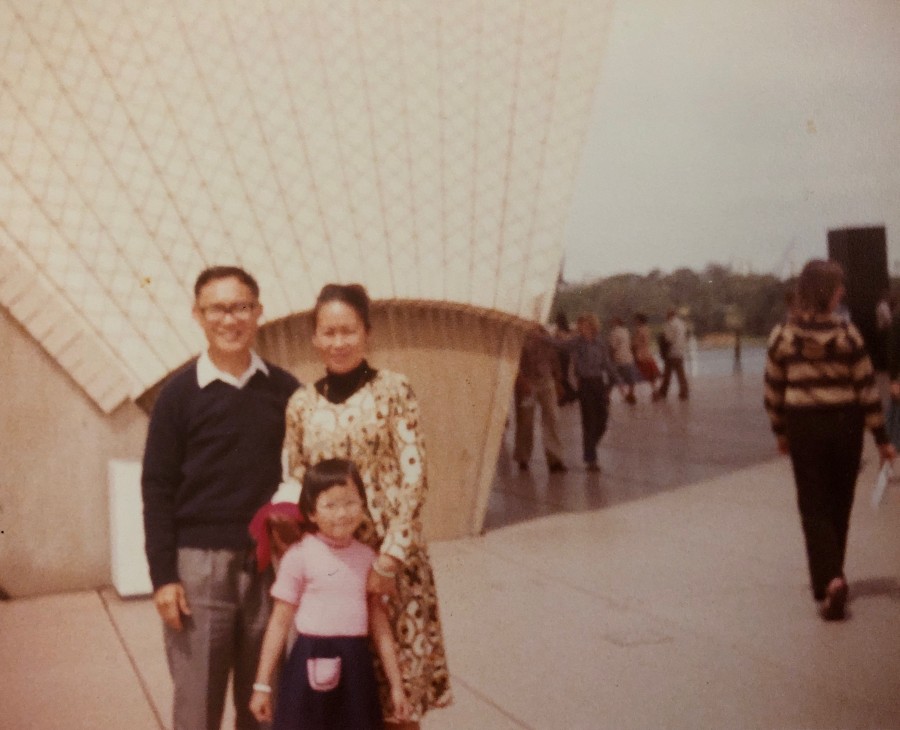

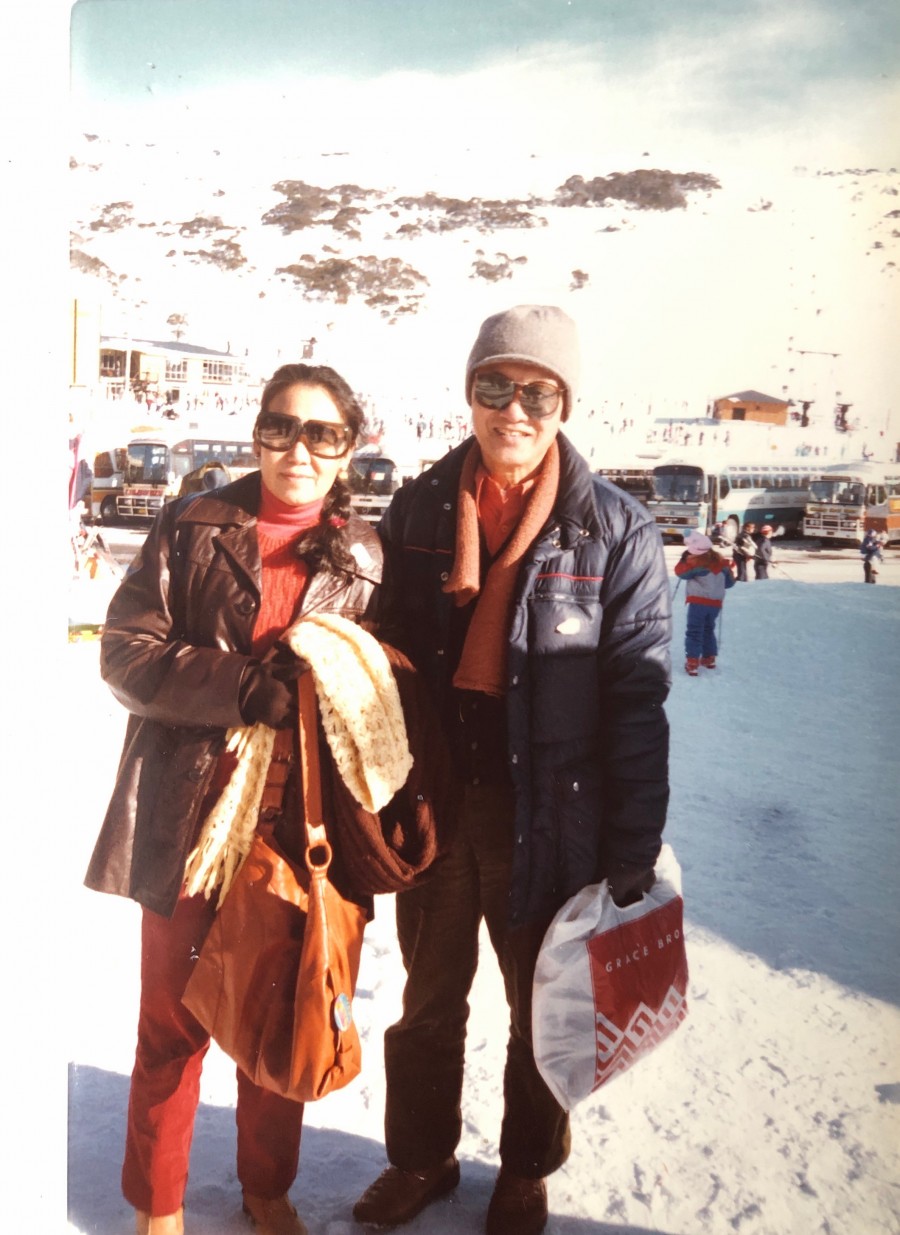

In 1976 we decided we wanted to move to another country because of the discrimination to non Malays. This included Chinese and Indians. Frances put the word out and was offered several positions. He was offered jobs with the University of Christchurch in New Zealand, the University of Sussex in London and a position at Sydney University in Australia. We chose Sydney because it was a city that we wanted to live in and warm in climate. When we arrived we moved into a house in the suburb of Denistone.

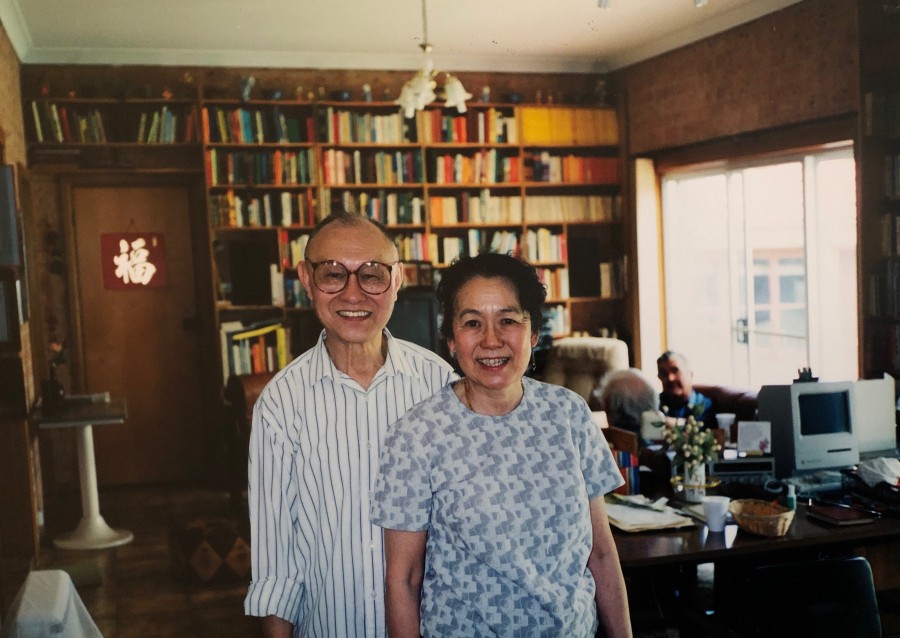

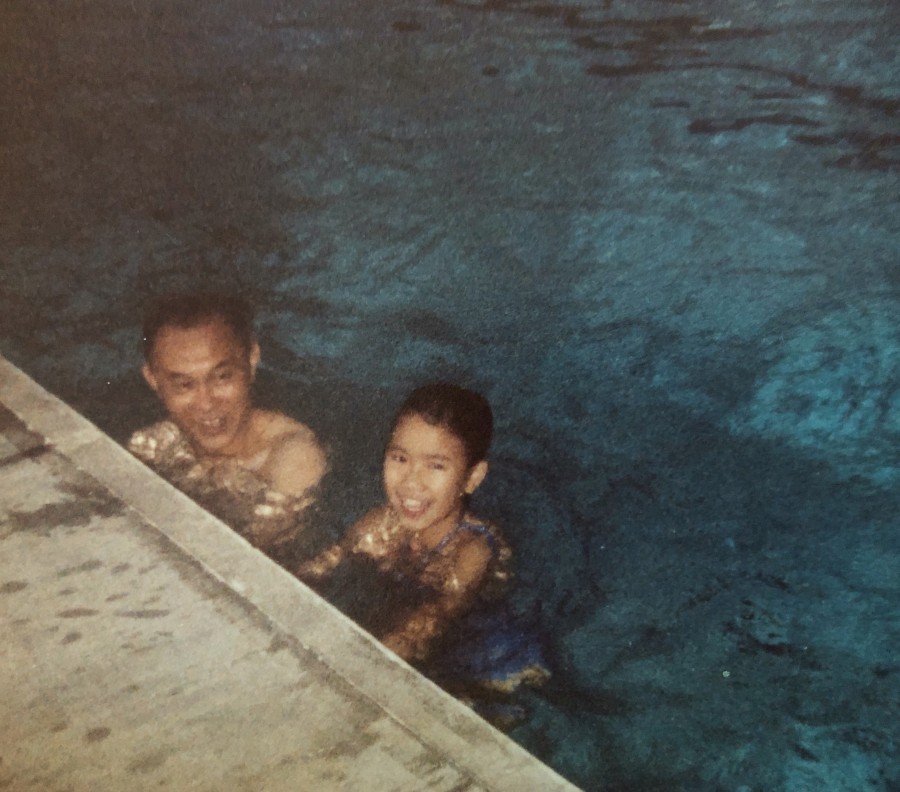

Francis started his job at the University of Sydney and he loved it. He worked there for many years. He was very reliable and a doting father. He would take Li-Chuen to school in the morning and then pick her up in the afternoon. We had a wonderful life living together in Sydney, working and raising our little girl.

When my husband retired, he started doing volunteer work at Mary MacKillop Place on Mount Street in North Sydney. Every day he’d take visiting school groups of children around and tell them about the life of Mary MacKillop.

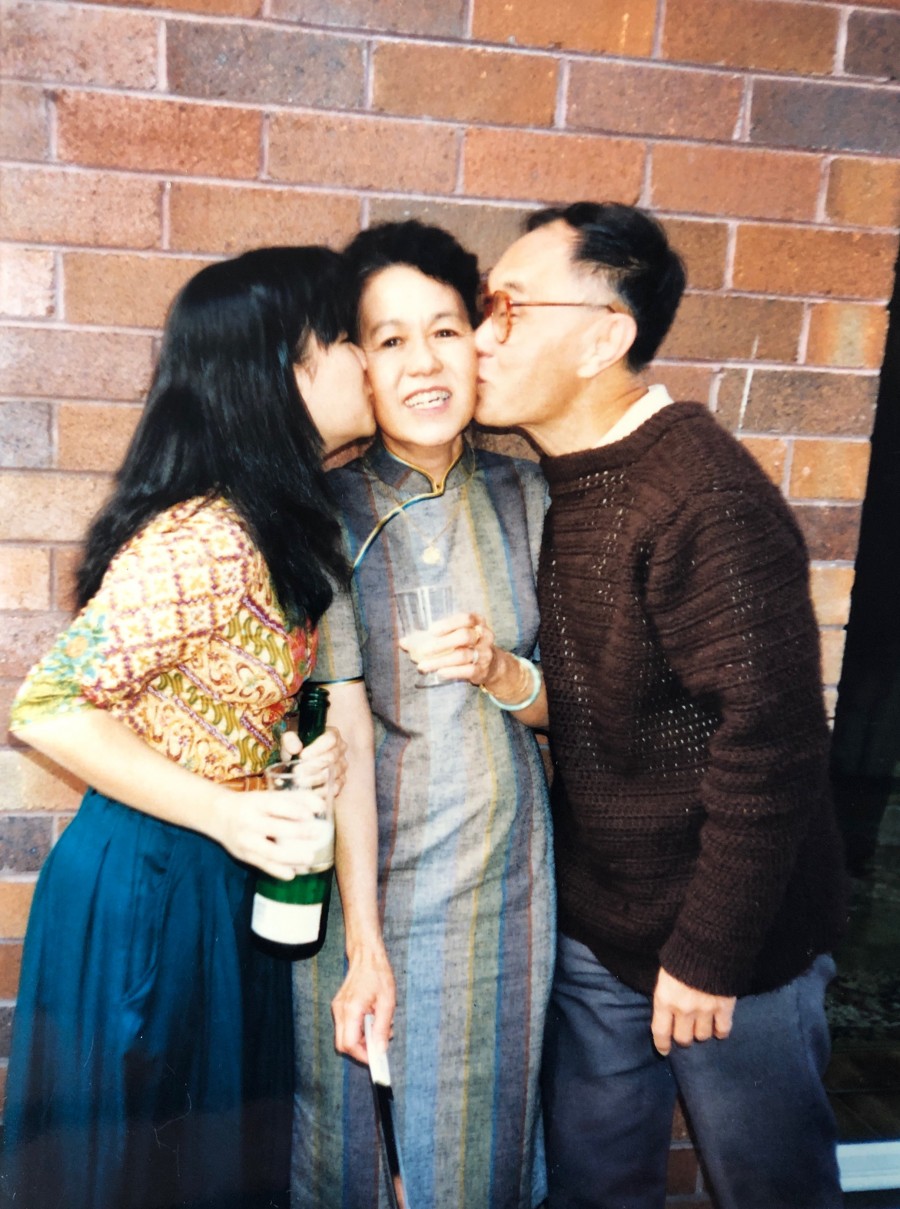

Francis became unwell after he’d had a fall. Every day he travelled home by train. He’d walk through a park in Epping on his way to the house. On this particular day he fell. He got up and walked and fell again. He sustained a bleed into his brain following a bad fall. He was in hospital for quite a long time and after brain surgery, he went to a nursing home called Chesalon Care in Beecroft. It was a very difficult time. He deteriorated and never came back to where he was. It was hard seeing him suffer. Over time Francis started to lose his memory. There was a stage when he didn’t even know who I was. Eventually he had to go back to hospital and he passed away. This was in 2009. He was 83.

He was my best friend. As a person, Francis was a thinker. A quiet thinker. Half the time, you didn’t know what he was thinking. The thing was he didn’t communicate much. Even with me, he didn’t communicate much. A lot of our communication over the years was non verbal. We did everything together. We married in 1969. We were married for forty years. We had Li-Chuen together and she has brought both of us so much joy. We had a wonderful life together.

Family Life

Francis and I were married in Kuala Lumpur on the 19th of December, 1969. We moved into a house in the suburb of Pantai Hills. It was a beautiful, hilly area and quite prestigious at the time.

At this point, I was still working for the Ministry of Education as a consultant. Francis had left the brotherhood and resigned as Headmaster of St John’s School for Boys.

Francis was offered a job almost straight away at the University of Malaya as a Senior Lecturer. He was very happy because it was the sort of work he had been wanting to do for years.

A couple of years later, I fell pregnant. My younger sister told me, "Hey, I think you're pregnant." I said, "How do you know?"

"It's just the way you walk."

Sure enough, I was. Francis didn’t know how to react. He was pacing up and down the office and whatnot.

When Li-Chuen was two, we realised that it would be great for her to have a companion to play with. Someone that could help with babysitting. One of the teachers at my school employed a girl to help around her house. She told me to go to the girl’s village to see if she had any sisters who might be interested. My mother and I went to the village. When we got there we learned that all of the girl’s sisters had gone out to work for other people as domestics. There was one sister left. She was only twelve years old. She was standing at the door and my mother said, “Why not this little girl? She can play with Li-Chuen.” All I wanted was for Li-Chuen to have a little companion. And so we asked her and she said yes.

Her name is Ah Fah. Ah Fah means flower in Chinese. Ah Fah likes to call herself, Rose. Over time, she came to live with us. Ah Fah became a part of our family.

My gynecologist was an ex-student of mine. I had taught him at the boys’ school. Can you imagine? I was already forty-one at this point. The doctor wasn’t going to let me have a natural birth. And so he said, “Choose your day and just come in." I didn’t bother to choose a specific date. I was working in the Ministry of Education at the time.

Around the time I was due, the doctor called me. He said, "What time do you want to come in?" In Malaysia, there are two sittings for school, a morning session that starts at 7 am, and an afternoon session that commences at 2 pm. I said "Yeah. I will finish the morning session and then I’ll come in.” So at 3:30 pm on the 26th of August, 1971, I went into the hospital, and out came Li-Chuen.

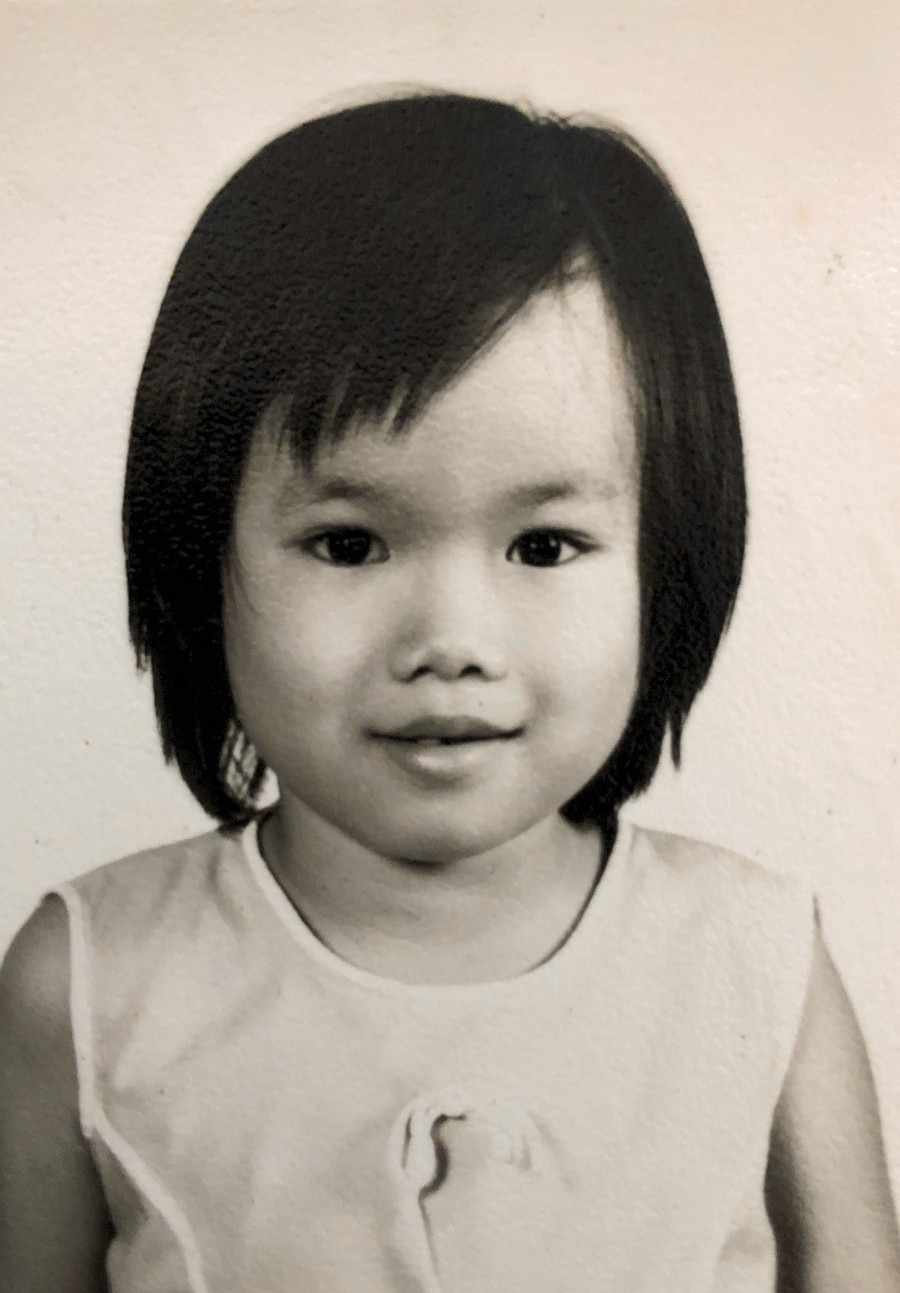

A friend of mine, who is a nun, Sr Letitia suggested the name, Li-Chuen. Her name comes from a Chinese story that’s too long to tell. It’s a name of historical significance. Also, this historical figure went on to marry someone with the surname Wong. And there's a story, a Chinese story behind that. Just as my name has a Chinese story behind it. So I thought, that's quite a good name.

When Li-Chuen was little I was well supported. At that time I had Ah Fah already there. Also, I had two maids. These three all lived with us as live-in helpers. We also had a gardener. They would all help. There was no problem, whatsoever.

In 1974 we decided to emigrate for Li-Chuen’s sake because the education system in Kuala Lumpur was so horrible. She was about to start school, properly and we wanted her to get a good education and have plenty of opportunities. We were also really disappointed with the country’s leadership at that point.

Christchurch in New Zealand offered a job to Francis because his subject is comparative education in Southeast Asia. That is something quite rare that universities wanted. The University of Sussex in London also offered him a job and Sydney University offered him a position - all at that same time. Francis said to me, "You choose. If you say we go to Christchurch, we go."

I don't know Christchurch. I know London too well, too long. There's no point in going to Sussex. And I know if I go to Sussex, then I will be dominated by Joy and other friends there.

So I thought, start afresh, we come to Sydney. People said to me, "Why did you go to there? It’s a convict country. I couldn't care less.

I said, "I'll go there. The climate is good. And ‘convict country’, so what? I'm a convict too."

Australia

When we prepared for the move we learned that Ah Fah could not come with us. She wanted to come because she had been living with us all these years, but the Australian Consulate said that if she is to move to Australia with us we’d, "have to legally adopt her." So I have no problem legally adopting. After all, I've only got one child. The problem was that her parents wouldn’t give permission for her to be legally adopted. So I told her, I cannot adopt you now, you’re too old. They won’t let me adopt you.” So I couldn’t bring her across to Sydney as my family. So she had to be left behind when we emigrated.

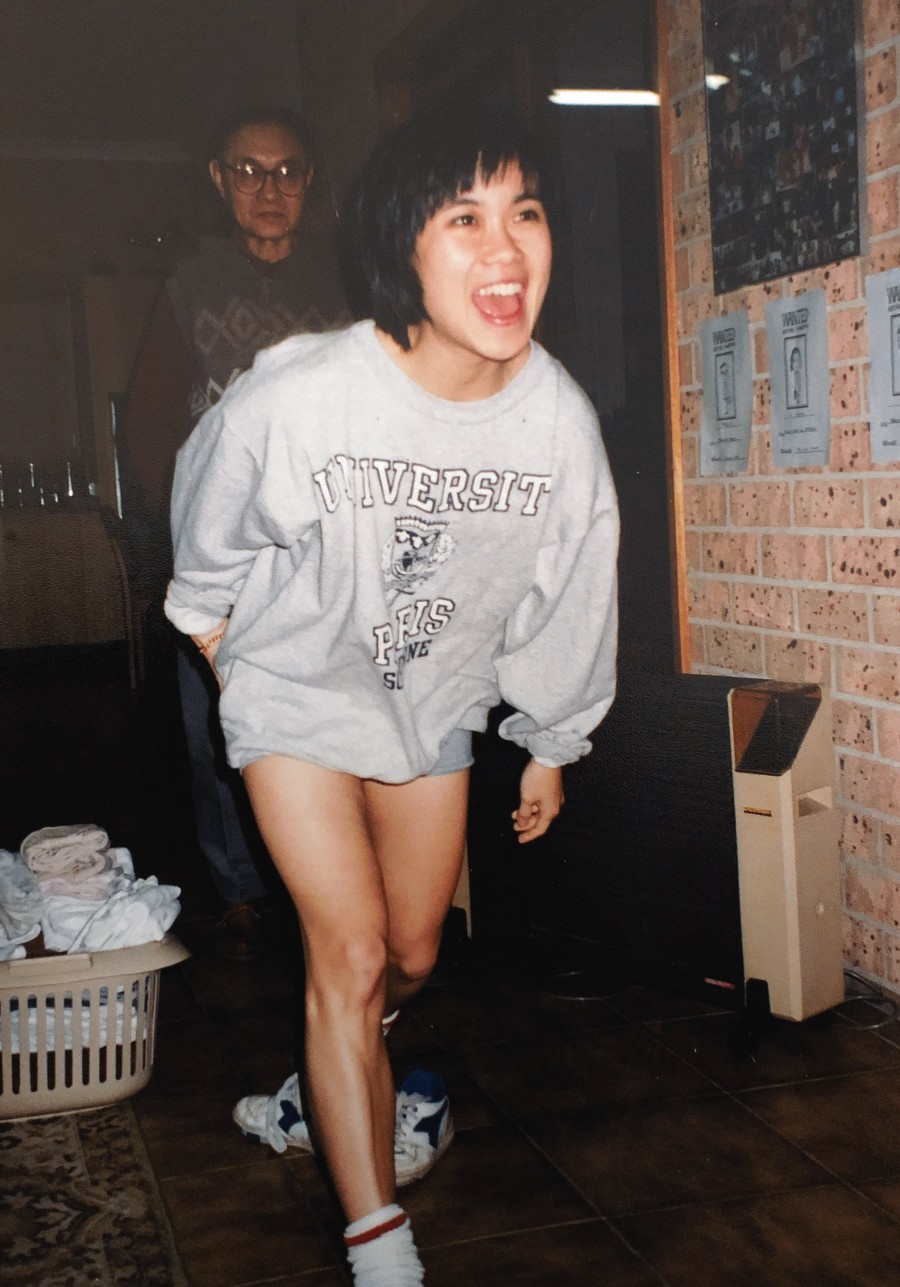

In 1976 we left Kuala Lumpur for Sydney, Australia. Li-Chuen was five. We arrived in time for her to start Kindergarten at Primary School. We settled in the suburb of Denistone because our friends the Foos were nearby in Carlingford and some other family friends of ours lived in Eastwood. Our families and the Foo family were close. I had taught Norman Foo, who I knew as Yeow Khean, back in Malaysia when he was about fifteen. He was a very smart boy and went on to do amazing things in Australia. He became the Emeritus Professor at NSW University and as a computer scientist, was a world leader in the field of Artificial Intelligence.

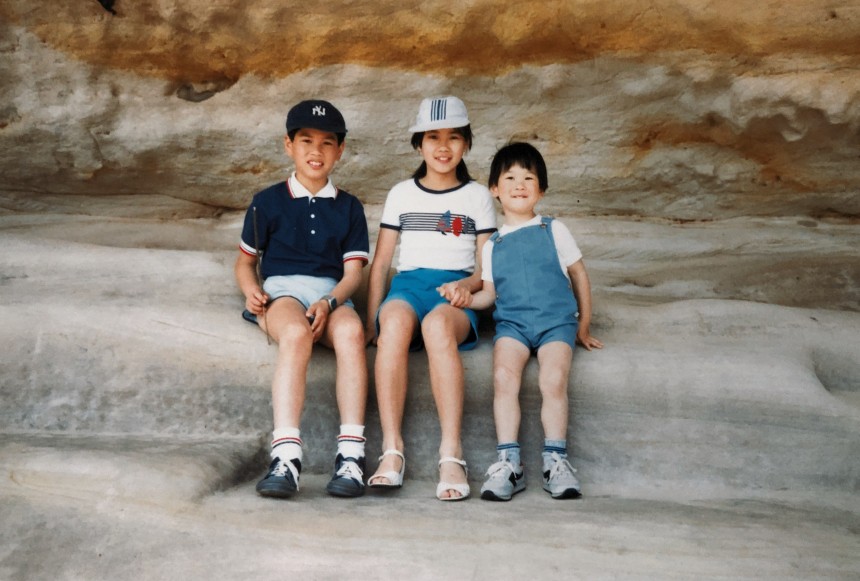

Over time we moved to Epping. The Foos ended up moving into our street, only three houses away. We have so many wonderful memories together. Li-Chuen is very good friends with Norman and Yokelin’s boys, Kerwyn and Lyndon.

So Francis started his job at Sydney University and he loved it. I started doing some casual teaching work but I hated it. I felt like I was just being paid to babysit. It was so different from regular teaching.

I decided I wanted to teach Chinese and so I took a position at The School of Community Languages. The lessons were taught on a Saturday. The government wasn’t offering language courses in a lot of High Schools at the time. If you wanted to study a language for your Higher School Certificate, you would have to go to a language school on a Saturday. I really enjoyed teaching there. The students were all year 11 and 12 students and so they really wanted to learn and to do well. I taught there for ten years. Around the time I started teaching Chinese in Sydney, I began to do volunteer work with the Royal Institute of the Blind (RIDBC) at North Rocks, working as a proofreader. I did this for two days a week for twenty years. Actually for more than twenty years.

Soon after we arrived in Australia, Li-Chuen started Primary School at Eastwood Public School. Francis and I had different ideas about where Li-Chuen should go to school because I wanted her to mix with all sorts of people. I say no, not only Catholics. I said one school must be a state school. The other school you choose. In the end I managed to get her to Eastwood Primary school and I thought that was nice. She still has her friends from Eastwood, and that is what makes me happy because we are all different. Then of course we agreed, she goes to state school in primary, then she goes to a catholic high school because Francis wanted her to go to a Catholic school that is in Strathfield, Santa Sabina College. It’s the most expensive school in the area now but back then it was the cheapest. She did very well there. She was awarded Dux of the school and with her results, was able to gain entry to Sydney University to study medicine.

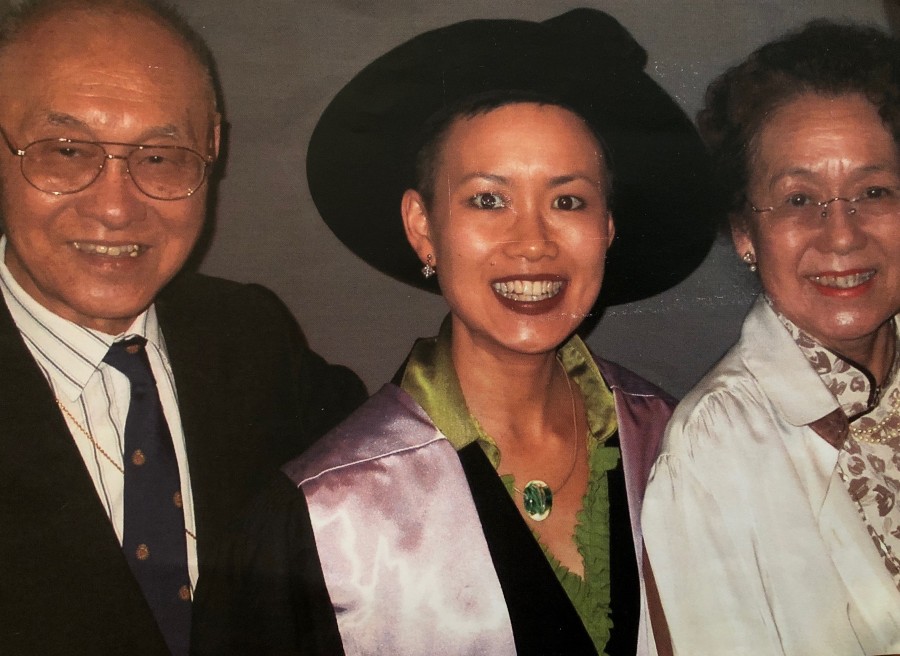

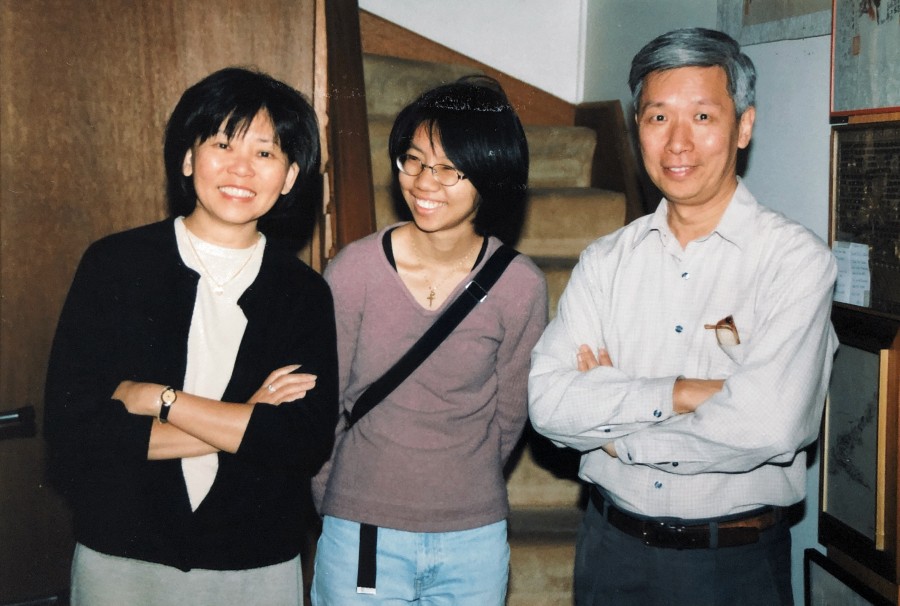

Li-Chuen is now a highly successful dermatologist and is the co-founder of ‘Sydney Skin’, a dermatology clinic in Newtown. Li-Chuen trained with a lady by the name of Maureen Rogers. She was the head of Dermatology at Westmead Hospital. Li-Chuen then went on to set up the practise with her colleague, Andrew Satchell, in Newtown. Li-Chuen still goes to Westmead Hospital once a week on a Monday to work. I’m happy about that.

I had read a lot that you can get what you want your child to be if you work at it. So I wanted Li-Chuen to be good in music. So in gestation, it was classical music all the time. Li-Chuen is very good at music. She started studying music at the age of three . Her music teacher’s name was Margaret Hair. We discovered that Li-Chuen has perfect pitch. She became both a brilliant pianist and violinist. She studied alongside a boy named Duncan Gifford, who has gone on to have a remarkable career in music, playing and teaching music all over the world. Li-Chuen could have taken this direction too, but thankfully, chose a rewarding career that didn’t result in her being away all the time.

When I was a child I had some training in piano but it didn’t really work. I had trouble reading the treble clef and the bass clef at the same time, fast enough. You know the lines for the left and right hand. I didn’t take lessons for long because my family couldn’t afford it. I guess it was coordination. It was never my strongpoint. Take swimming for example. I’m not terribly good. At one time I nearly drowned. When I was teaching in secondary school in Kuala Lumpur, we were at the local pool for a swimming program. One of the teachers says, “Come in. Don’t be frightened. I swim next to you.” So I jumped in and I bubbled up and bubbled up and went straight down. But I tried to overcome that. I did.

Another thing I’m not good with is my sense of direction. I can get lost. Even in Haberfield. This isn’t something new, I’ve always been like this. When I go out I need to go to my friend Penny and I give her the car and I say, “Where shall we go?” Then she will drive around the place. I will get lost. I can get lost for three hours, driving around and around and not be able to find my way home.

Since I was a child, during the Second World War, in Kuala Lumpur, something I had struggled with was my resentment towards the Japanese. The Japanese occupation of Kuala Lumpur had a lasting effect on me. We didn’t have enough to eat. Hungry all the time. They put restrictions on all of the food.

When they were distributing rice, my poor brothers would have to get up at four o'clock, five o'clock in the morning to go and queue up to get our ration of rice, sugar and basics. We feared the Japanese coming all the time. And in my case I remembered, I was already in my teens."Sing!" they would shout. I have to think, but then sing what? I don't know any of the Japanese songs. And if I didn't, they beat me. The Japanese soldiers, they didn’t have any respect for women.

So I thought how can I purge myself of this hatred for the Japanese? I decided to apply for a degree in Japanese Studies. I applied to Macquarie University. I drove down to North Ryde and asked to see the head of the department. I spoke to a Japanese woman named Zusie Chow. I told her about my experiences during the war and the wounds it had left. I said, “The reason I want to do this degree is because I want to purge myself of the hatred I have for the Japanese.” She granted me a position in the course.

I chipped away at the Bachelor’s degree over several years. It was very interesting. I learnt about Japanese history, language and literature. Reading their literature helped me to realise that we’re all the same. So the studies became a healing experience and it opened my heart up to the Japanese. This pleased me a great deal. I have since become very good friends with quite a few Japanese people. People whom I am truly fond of.

As a parent I have so many wonderful memories and proud moments. Li-Chuen has done so well. She certainly hasn’t let me down. But then my son in law, Michael O’Neill was also the dux of his high school at Christian Brothers in Lewisham. The thing is he never said he was. I only learned when I visited the school and saw his name on a plaque. It’s one of the things I like about Michael and well, my whole family, is that modesty. Francis was always very humble, too. I’m not fond of bragging. We are all ordinary people and there is no person greater than the other. I feel that we are all equal. We are born into this world. We could have been born beggars or into royalty.

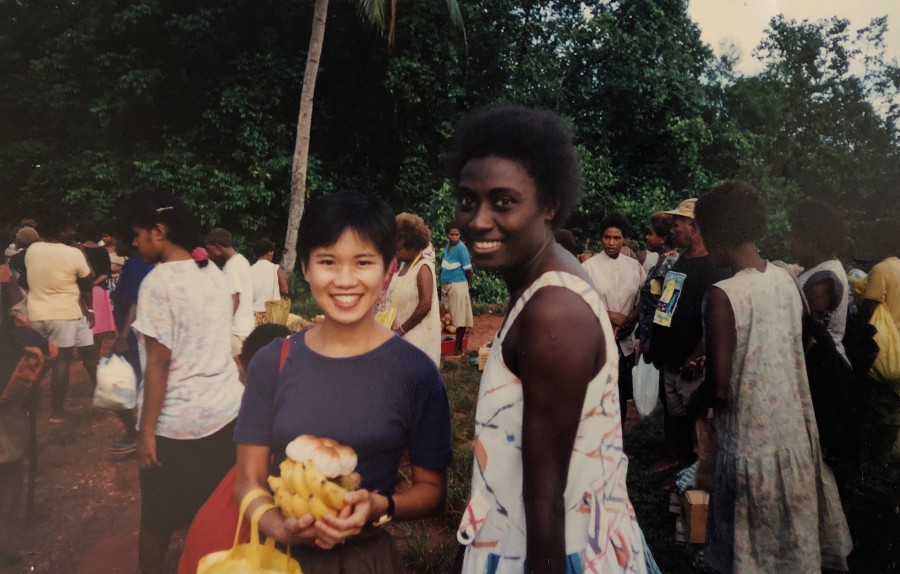

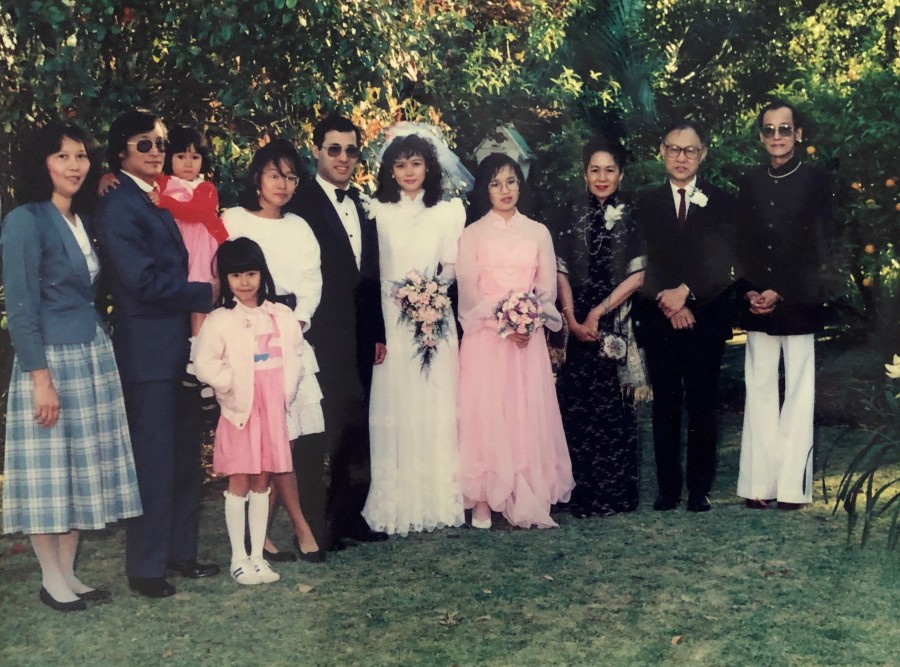

A very happy family memory I have, that was a proud day for Francis and I, was when Li-Chuen and Michael got married. They married at Mulgoa, where Edmund Rice Camps are held. It was beautiful. The priest was black. The altar was a tree trunk and it was in the Edmund Rice Camp. It wasn’t a big show off wedding. I liked that modesty.

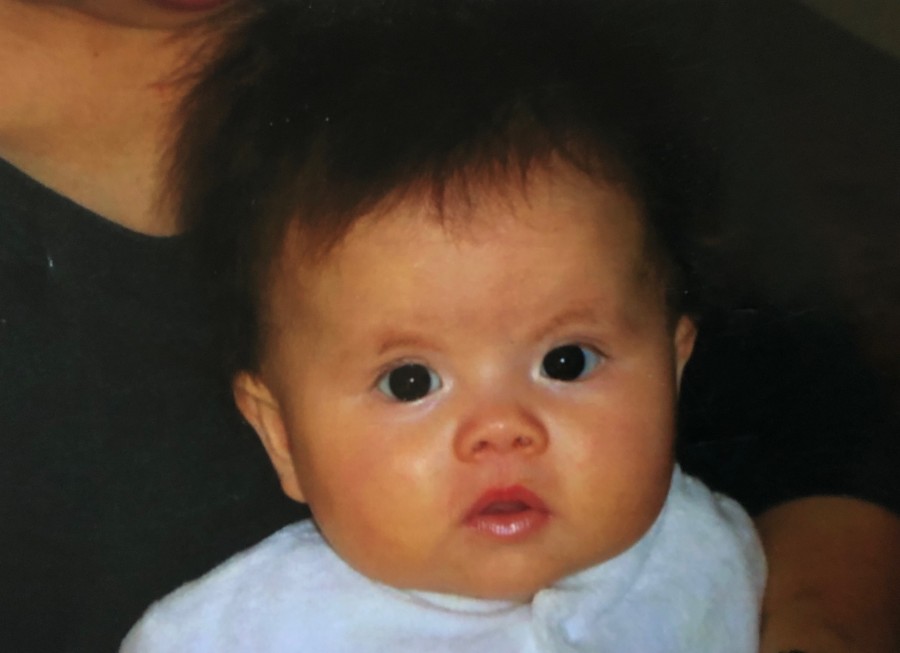

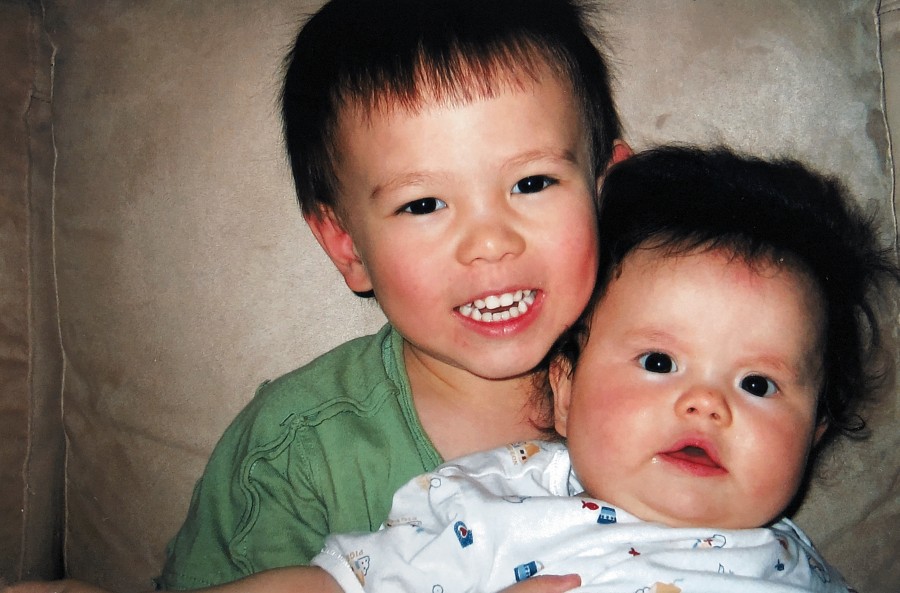

When my Li-Chuen told me she was pregnant. I was so excited. I thought, whatever comes from her, will be precious. Li-Chuen sent me the ultrasound picture of my first grandchild, Ned, in her tummy. That was the greatest thing! That picture is all framed up and on display in my house. He was such a beautiful baby! They all are.

Every evening when the sun goes down I walk across to their house and it’s my time with them. Straight away, one of the kids will pour me a glass of red wine when I get there. They play with me. A lot of the time I eat with them.

My grandkids call me Po Po. In Chinese, Po Po means mother of my mother. If I was the mother of their father, they would call me, Nai Nai. It’s fantastic. Some grandparents may feel that because there are two generations between them and they want to maintain their dignity. To me no, they are friends. They are babies. They give me the proper respect but they play with me. My feeling for my grandkids is just love. An exchange of love. It’s a close feeling.

You can play with your grandchildren. As a parent, when your children are young, the role is different. There’s more of an element of teaching and guiding that is required. A parent’s duty is different. They need to teach them the right thing. They need to train. For grandparents, it’s to simply give them love. I love my grandkids all the same but I have a special relationship with each of them.

Ned is now 16 and still not ashamed of telling me he loves me.

Nellie is a soft girl. She puts love notes all over my house. That’s very touching. ‘Love you Po Po, Sleep well.’ If it is night time she’ll put a note somewhere and I’ll see it.

My little Niamhy. She is so smart, already. Recently I was looking for photos of a young me for these memoirs. She said, "What are you doing Po Po?" I said, "I'm trying to find a photo, a younger photo of me."

And then immediately, came out, "Po Po you are 90. When you were young, there wouldn't be cameras to take you." Immediately she could think that. So I tell myself, "Gosh, how can I, how can I talk to these people?"

I feel grateful that at my age I still have people who would like to talk to me. I will still have friends like Penny who would want to go out and have a meal with me and talk with me. I’ve always been very talkative. Sometimes I feel, “God, I’m 90. I mean, am I talking rubbish?”

I met Penny a long time ago when I joined a singing group in Haberfield. We drifted towards each other and somehow or other we got on. Whenever she is free we get together and have lunch. If we go by car, I drive to her place and she drives. This is because with my sense of direction, I’ll get us lost.

So I have lots of friends that I see or talk to regularly on the phone. I have been friends with so many of them for so long that their families are like my family. I just said goodbye to my friend Darryl (Alexandra). He is the partner of mine and Francis’ nephew, Leonard. He comes to visit me quite often for lunches and chats.

Claire and I have been friends since the convent school after the Second World War. Recently her son took me out with his family because his wife had a 60th birthday party. Claire lives in Perth. I used to visit her quite often in Perth. We talk on the phone a lot. Our friendship will never disappear.

Monica has been a good friend for a long time, too. She lives in Singapore. Any time I want a change of scene I can visit Monica. We talk regularly on the phone. Even her grandchildren call me from Singapore.

My Siblings

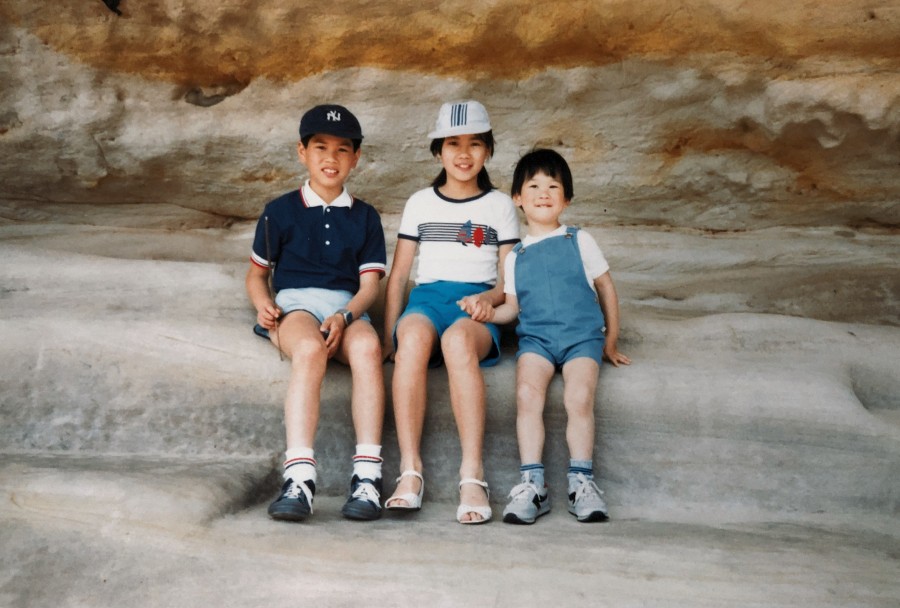

I am the eldest of the seven children that my parents had. I have four brothers and two sisters. This is us.

- Chiew Pek-Lin

- Chiew Thiam Yew

- Chiew Thiam Choy

- Chiew Thiam Seng

- Chiew Pek-Kwan

- Chiew Thiam Loy

- Chiew Pek-Chun

Thiam Yew was an Insurance Salesman. He spoke Tamil. Very few asians can speak the language. This means that he was able to sell insurance to all the Tamil speakers. He became very rich. He ran away with his first wife, Sau Lin when they were seventeen. The family wasn’t invited to the wedding but we received a photograph. When he became rich, he left his wife and their three kids, Wing Sum, Wing Lin and Jenny in a house he had bought for them. Jenny went on to become a manager at Cathay Pacific Airlines. His second wife, Sandy was his secretary. They had three children together: Ronald, Cindy and Sharon. Thiam Yew passed away not so long ago. He had cancer. I encouraged a reconciliation between him and his children before he passed away. All of his six children were there with him when he died.

Thiam Choy lives in Kuala Lumpur. He has three girls and a boy. He has always loved to play badminton. He doesn’t have much money but his kids will get him whatever he needs. As a young man, Thiam Choy was working as a clerk in a bank. He would sneak out from his work to participate in badminton competitions. This led to him losing his job.

Thiam Seng was a dressmaker and also a chef. He died of HIV in the mid 80s when not much was known about the virus. I sponsored him to come to Sydney and work as a waiter at my restaurant. Then I paid for him to go to Paris to learn dressmaking. This was long before he was sick.

He was such a perfectionist. He would only make wedding gowns for people. He would spend so much time on these dresses and yet he would make no money.

We had a restaurant together. Then he was able to start a restaurant of his own called ‘Malaysian Home Cooking.’ He did very well with the restaurant and was able to buy a flat in Manly. Thiam Seng was dying in Hospital. I went to see him. He cried, saying, “I’m so sorry that I have no time to repay you for what you’ve done for me.” He became a catholic the night before he died. Sr. Antony asked him if he would like to belong to a religion. He said, “Yes. Catholicism. I’d like to follow my sister.”

Thiam Seng had a lot of friends, many of whom were well known figures. The Australian Cricketers and brothers, Ian and Greg Chappell were his best friends. They would come to his restaurant to see him.

Thiam Loy is my youngest brother. When my father died he was only five. I am eighteen years older than Thiam Loy. I had to look after my mother and help bring up Thiam Loy, Pek-Kwan and Pek-Chun. Thiam Loy wanted to go to England to study accountancy but he spent most of his time playing the guitar. I told him if he could pass ‘Part 1’ of the accountancy course, I would fund his studies in England. He didn’t like this and thought I was showing favouritism because he thought I helped Pek-Chun to get to London. I didn't. Thiam Loy started to neglect his studies and focussed on playing the guitar. We were all worried about his lack of effort in school studies and how this would reflect on his future. I decided to send him to Penang Boarding School. This cost me a lot of money but it was worth it because it got him through school. When Thiam Loy came out of boarding school he didn’t achieve the marks he needed to get into university. After that he worked for my boyfriend for the ‘Unilever’ Firm. Thiam Loy got married and he and his wife had three girls. In the 1980s I sponsored his family to come to Australia. He lives with his family in Dural (Sydney) now.

Pek-Kwan lives in Singapore. She is married and has two grown up boys but her husband died.

Pek-Chun is my youngest sibling. I am twenty years older than her. When she finished high school she went to England to do Nursing. I didn’t have to pay a cent while she was there. I just paid for her airfare. She found a hospital in Bath. The moment she got into the hospital she started working. Pek-Chun worked as a Nurse throughout her career. She married a very clever man who was actually the Trade Commissioner of Malaysia. Together they went and lived in Japan for a while. They have four children together. One of Pek-Chun’s daughters, Suat Ling Chua, is here in Sydney and is a trained accountant. She is now married to a man named Quincy, who works at the ATO and used to work with my son in law, Michael.

For Others

I’m happy that I’ve been able to help to educate others. Not just as a school teacher, supervisor and principal but to have been able to support others since then. I have educated my siblings. I'm still paying for this girl who is studying music at a Music College in China. She is on her way to becoming a teacher of the Erhu. I don't mind it because I feel, look, I have got the money. Why do I want to keep it for? Let it go to those who could use it. In that respect. I feel some people may think I'm stupid, knowing I’ve got the money and I want to spend it on other people, but I feel happy about it. Some of the students I’ve helped didn’t succeed the way they hoped. This makes me feel sad but I feel glad that I was able to give them a chance. It gives me satisfaction to give people opportunities they wouldn’t have been able to have otherwise.

I’ve always done volunteer work. I’m fortunate to have been able to help others in my life. Back when I was living in Malaysia, I turned up at the prison in Kuala Lumpur and offered my services as a writer, to help prisoners write letters. So I helped the prisoners to write letters home to their families and friends. While I would work on letters with them I’d try to get to know them and learn about their situations. If people can talk out their problems we can try and find the answers to the hows and whys? I would really try to get to know them and find out how they think - with the aim being that through listening and advice, I could help them more in the long term.

I tried to do this again, here in Sydney, quite recently. It was too tricky. I went to the library to find out where the prison is. I was a bit worried that I wouldn’t know how to get there.

So yes, I still want to go and help because I’m alright. I think, my mind is still working okay. I feel, if I can help, why not?

I proofread for more than twenty years for the Royal Institute for the Deaf and Blind. More than twenty years, until they said, “We don't need you anymore.” I would sit with another worker, who was blind and we would proofread the braille together. So I would be reading with a blind girl. She would check the braille and I would read the print. We would take turns reading. Either she read and I checked or I read and she checked the braille. When we read across something interesting, we’d have a discussion about it. My friend Tristan who is still there will call me and say, “I miss you.”

Tributes

The Late Professor Norman Foo

This is a tribute taken from Norman Foo's Biography on the University of New South Wales website.

Here is the story about Peklin. She is eternally "Miss Chiew" to a whole generation of Victoria Institution boys and girls who were privileged to be taught by her. Me (Norman to you all and my relatives, but always "Yeow Khean" -- that was my school name in VI -- to her) in the years 1956 and 1957. You would think just 2 years is not enough time for a teacher to impress her devotion and care on her students. Wrong! Peklin is one of possibly five teachers I hold in great esteem and affection, and like most of the others it is not the number of years but the quality of teaching and example that mattered. Her good karma stems from her irresistible impulse to help anyone in trouble, and her outrage at injustice.

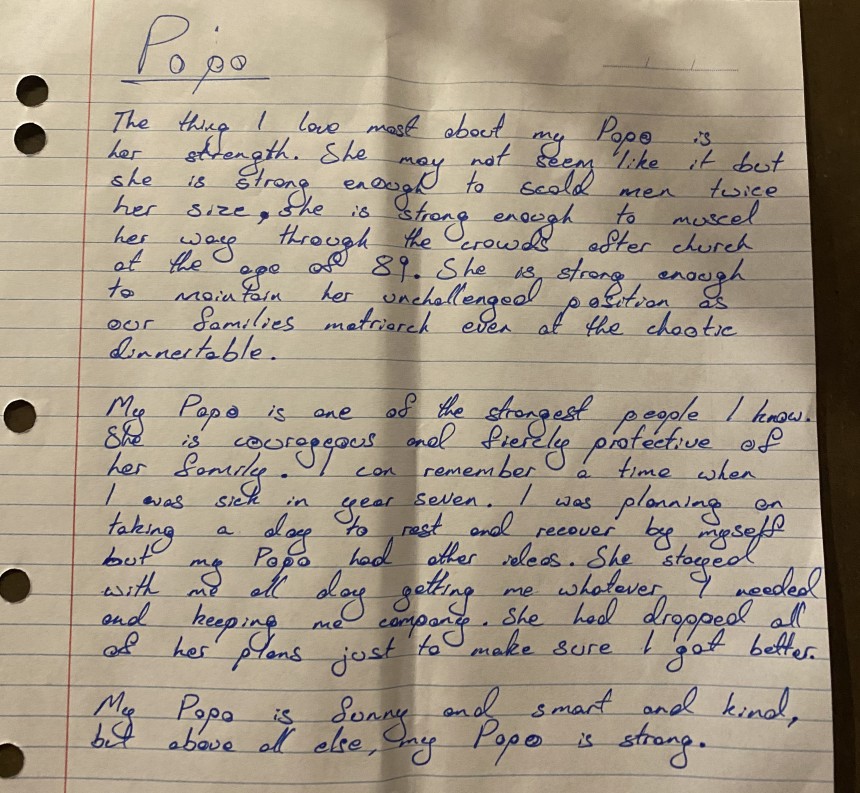

From Ned O'Neill (Grandson)

The thing I love most about my Popo is her strength. She may not seem like it but she is strong enough to scold men twice her size. She is strong enough to muscle her way through the crowds after church at the age of 89. She is strong enough to maintain her position as our family matriarch, even at the chookie dinner table. My Popo is one of the strongest people I know. She is courageous and fiercely protective of her family. I can remember a time when I was sick in Year Seven. I was planning on taking a day to rest and recover by myself but my Popo had other ideas. She stayed with me all day, getting me whatever I needed and keeping me company. She had dropped all of her plans just to make sure I got better. My Popo is sunny and smart and kind, but above all else, my Popo is kind.

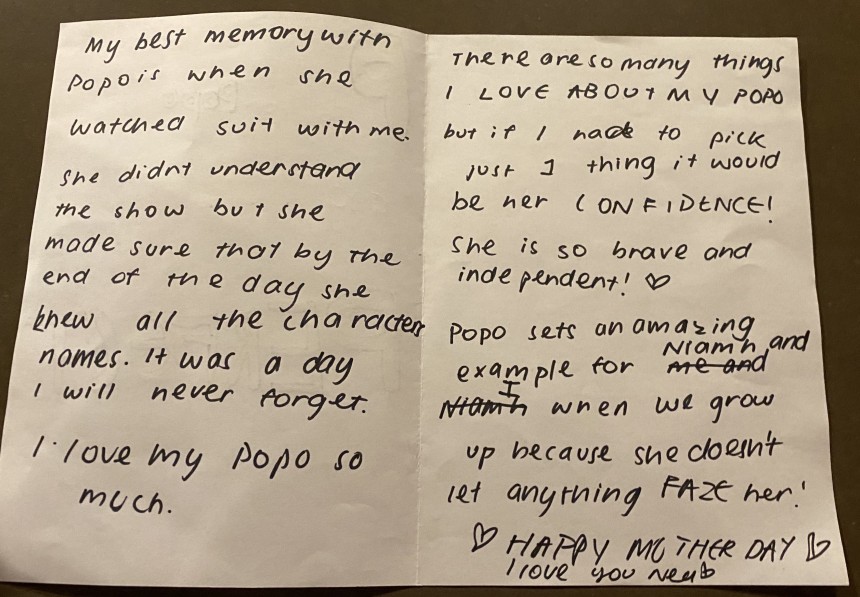

From Nell O'Neill (Grandaughter)

My best memory with PoPo is when she watched Suits with me. She didn't understand the show but she made sure that by the end of the day she knew all the characters names. I was a day I will never forget. I love my PoPo so much! There are so many things I love about my Popo but if I had to pick just one thing, it would be her CONFIDENCE! She is so brave and independent! PoPo sets an amazing example for Niamh and I when we grow up because she doesn't let anything phase her!

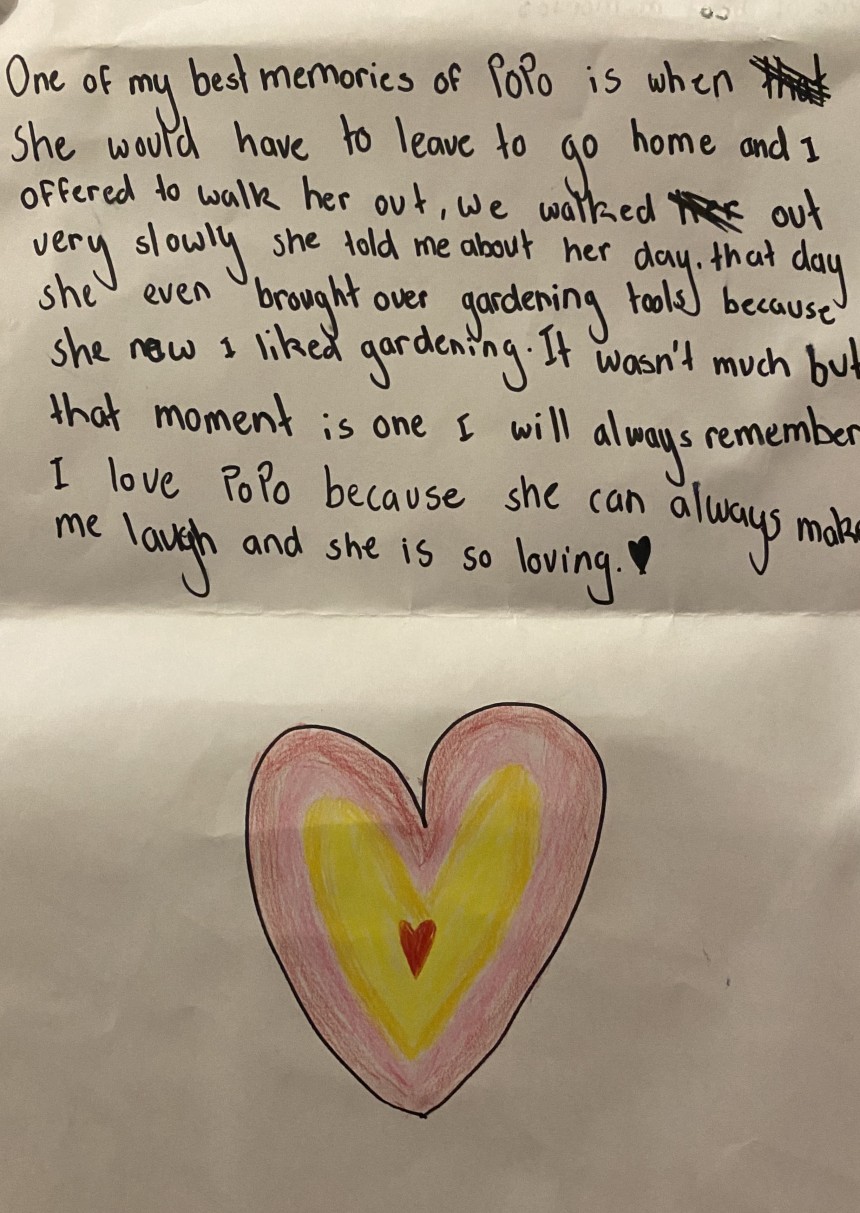

From Niamh O'Neill (Grandaughter)

One of my best memories of Popo is a time when she left to go home and I offered to walk her out. We walked out very slowly and she told me about her day. That day she had even brought over her gardening tools because she knew I liked gardening. It wasn't much but that moment is one I will always remember. I love Popo because she can always make me laugh and she is so loving.

From Tristan Clare (Friend and former colleague at The Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children)

I worked with Pek-Lin for several years at the Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children. The RIDBC changed Pek-Lin’s day there so that we could work together, proofreading texts in different languages. We covered a lot of texts from a range of literary works to novels. Pek-Lin is a formidable woman. She’s very knowledgeable about different languages and her French is excellent. So we worked closely together every Thursday for a couple of years. Pek-Lin is such an interesting person! I’ve always enjoyed our discussions together. We’d often have really in-depth talks about a great many things from different cultures to things of a more philosophical nature.

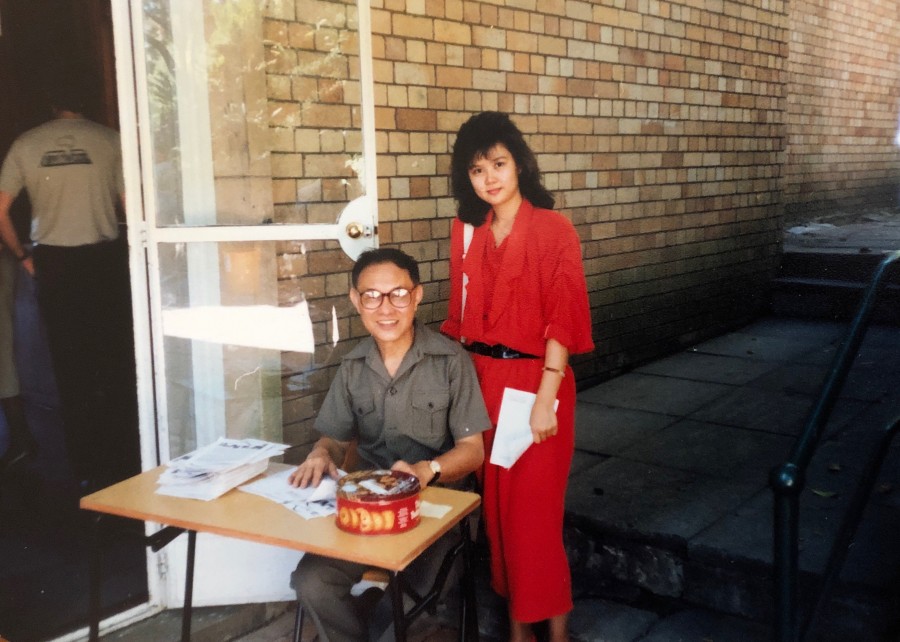

Pek-Lin's pupils from the Upper Sixth classes of 1959, 1960 and 1961 at the Victoria Institute (V.I.) school in Kuala Lumpur hosted a reunion dinner for her on a visit to Malaysia in May, 2008. The following link details the event.