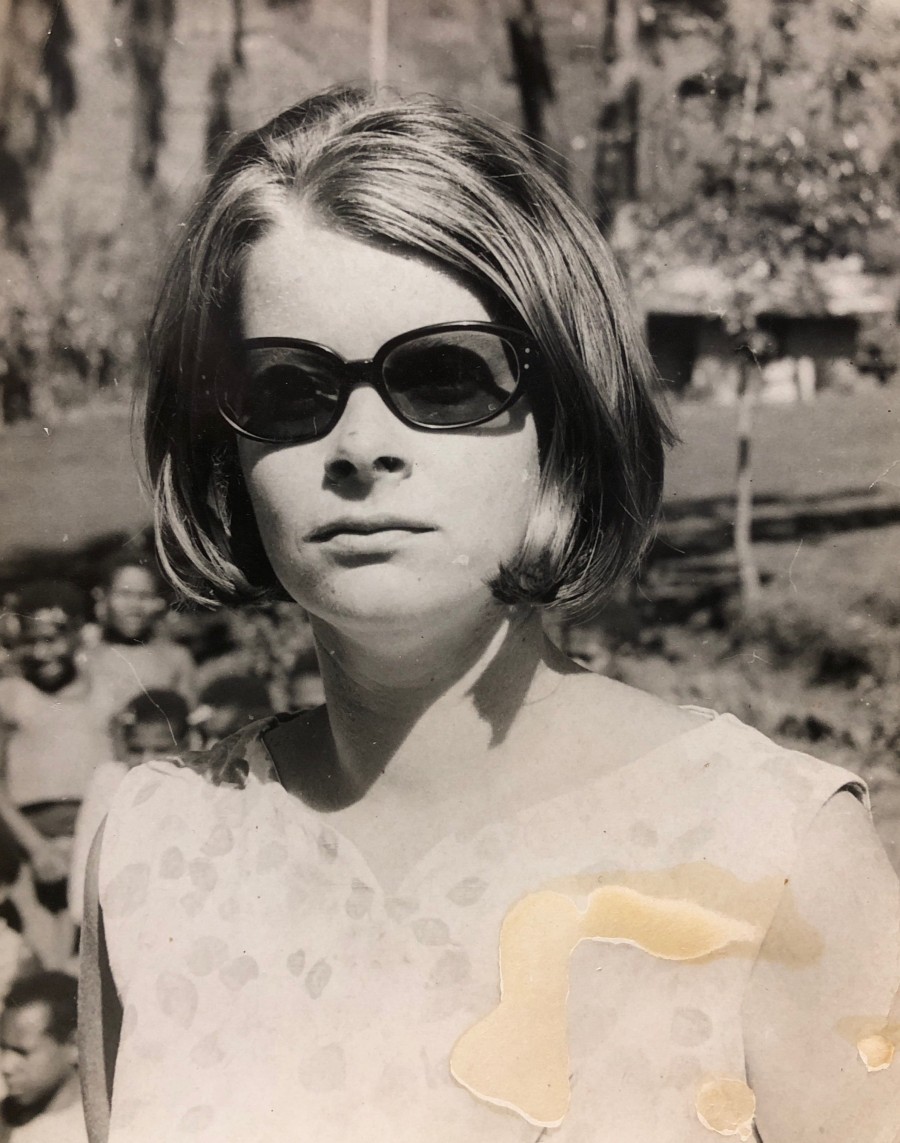

Judith Molloy

Born 1st of November 1941 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Early Life

My name is Judith Molloy. I was born on the 1st of November, 1941 in Sydney, Australia.

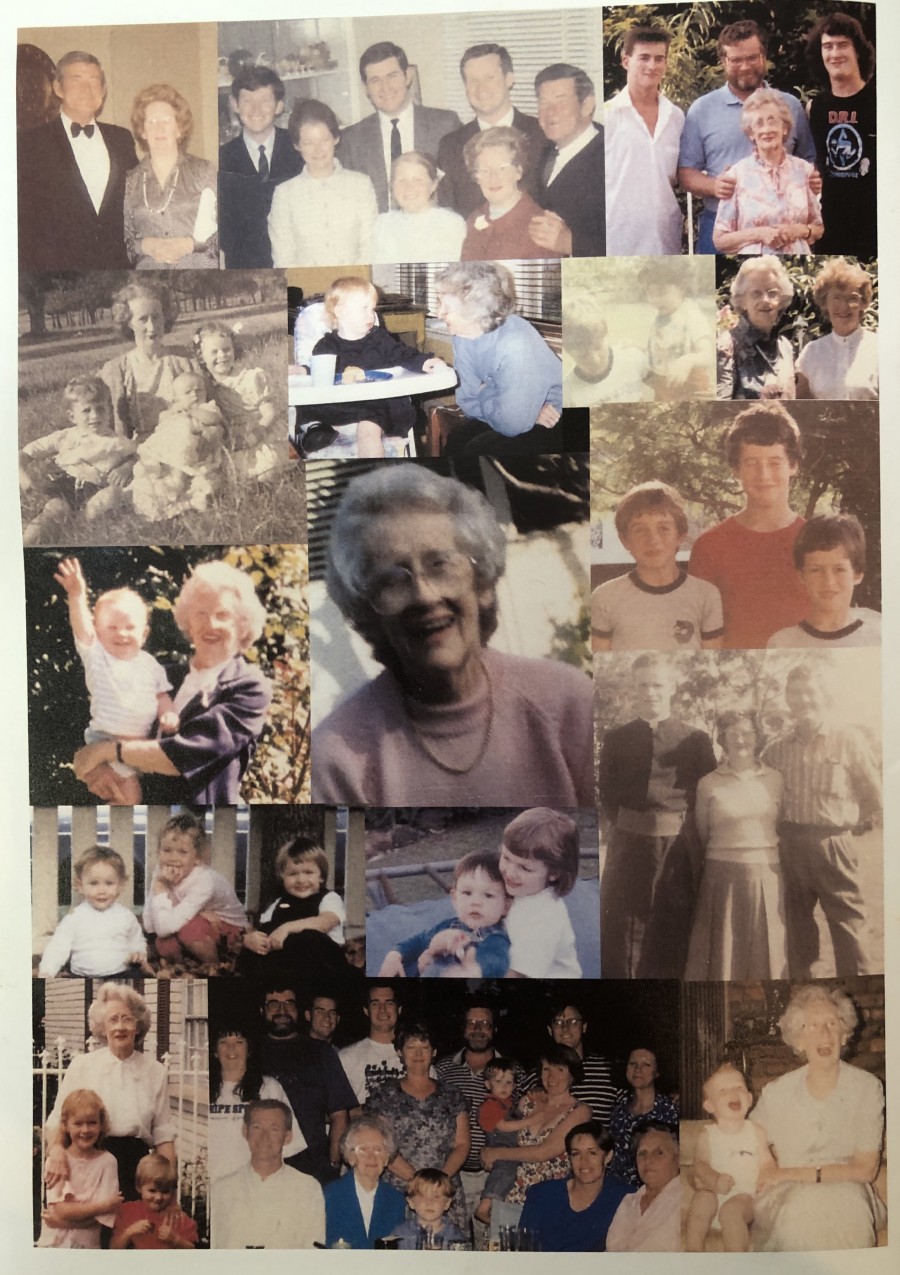

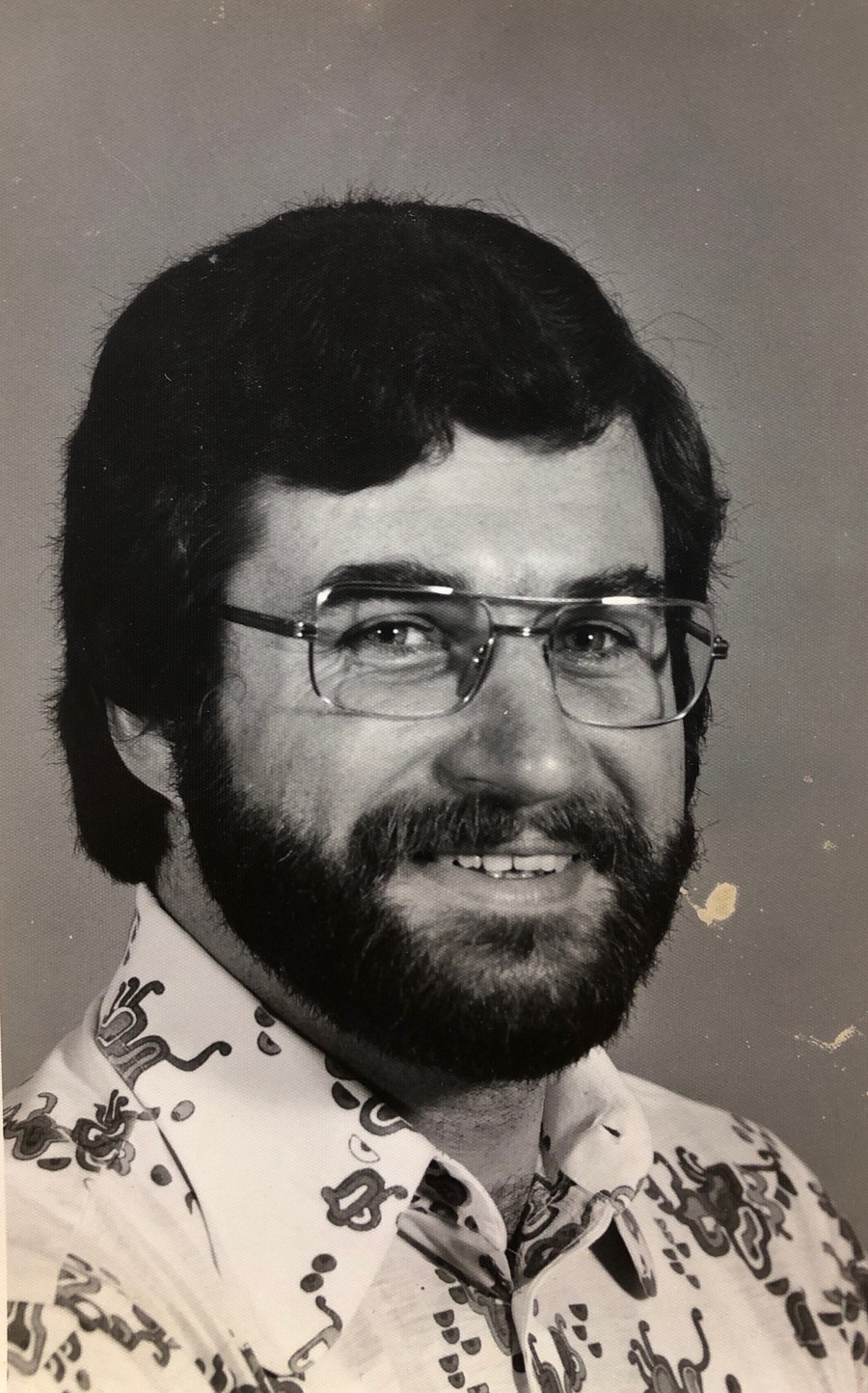

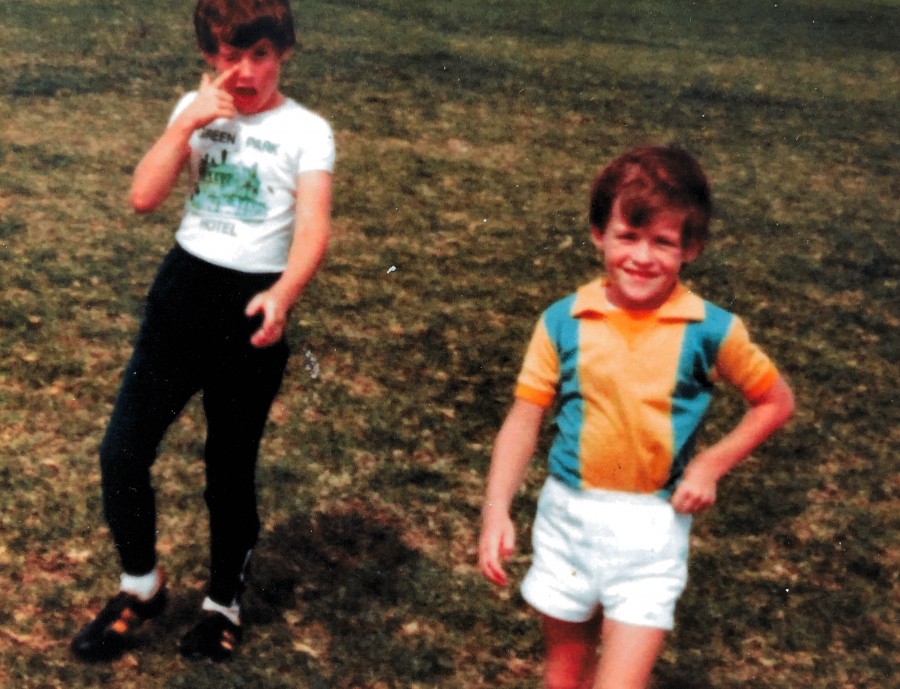

Over time my brothers Tony, Chris and Michael were born. As children we lived on Ramsay Street in Haberfield. Being so close to Algie Park, it was our playground. Two other boys, Bruce and Trevor joined the group. It was quite a bit later that our sister, Margaret came along.

Tony and I are very close in age. There is fifteen months between us. There was a couple of incidents over the years where I injured Tony. On one occasion, we were in the back shed. I reached up to grab a rake and when I pulled it down, it hit him on the head. He went inside the house, crying to Mum. None of us were ever encouraged to cry and so we were all tough as nails, in a way. Tony was crying and Mum must have been doing something in the kitchen and she said, “Oh you’re alright.” Anyway, when he turned around, there was blood running down the back of his head.

One time when we were even younger, I picked up this thing in Dad’s workshop. It was a stick in a tin of cement that had hardened. I chased Tony up the yard with it. As he opened the back door I hit him with it. We were both little kids. He got a hairline fracture of the skull. We used to dine out on all the stories about all the things I did to Tony.

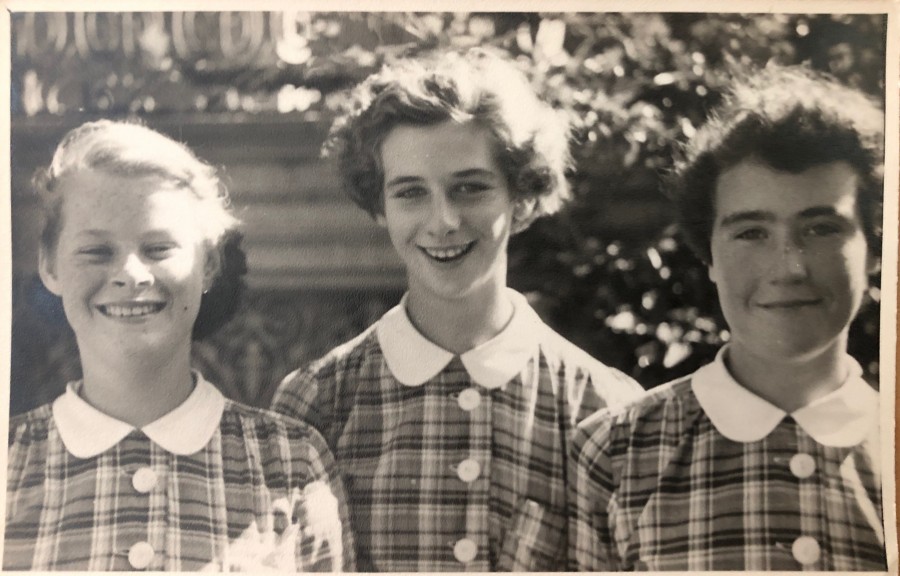

We all attended St Joan of Arc School at Haberfield. I was dux of Year 6 and received a book. After primary school, the boys went to De La Salle, Ashfield and the girls went on to Domremy Catholic College.

Soon after going to Domremy, I was diagnosed with Polio. After three months in hospital, I was allowed to go home to fully recover and to continue physiotherapy. As a result of my illness, I missed the rest of the school year.

When I returned to school I had to start Year 7 all over again. After completing Year 7, they made me skip Year 8 and rejoin my original cohort in Year 9. One of the problems I had by this stage was that I wasn't terribly fond of school at all. My life had changed quite drastically really. And that's how I came to leave school at the end of the third year, despite all kinds of promises to my parents. So I got jobs and then I did different things.

My brother, Christopher went on to study at the Seminary. When I came back after my first stint in New Guinea, he was there. He said to me that he didn’t think he could cope with the solitude of the priesthood. I told him he should just get a leave of absence for a year. And he did. He never went back.

Haberfield

Haberfield was a very different place in the 40s and 50s when I was growing up. There was a shop on the corner where Dolcissimo is now. It was a mens’ Haberdashery store. There were three banks in Haberfield. The building where Papa’s is now was once a National Australia Bank. There were two cake shops. Icin’s Cakes was where the current newsagency is now. A good friend of my parents, Uncle Phil, ran a Pharmacy on Ramsay St, where Lorena’s Boutique is now. Uncle Phil was married to Aunty Beryl. She had reddish hair and came from Wales. Uncle Phil’s parents came from Poland. They were Jewish. Aunty Beryl wanted me to marry her son, Bruce. There was a movie theatre on Ramsay St, where the IGA is now. We used to go to the movies there on Saturday afternoon.

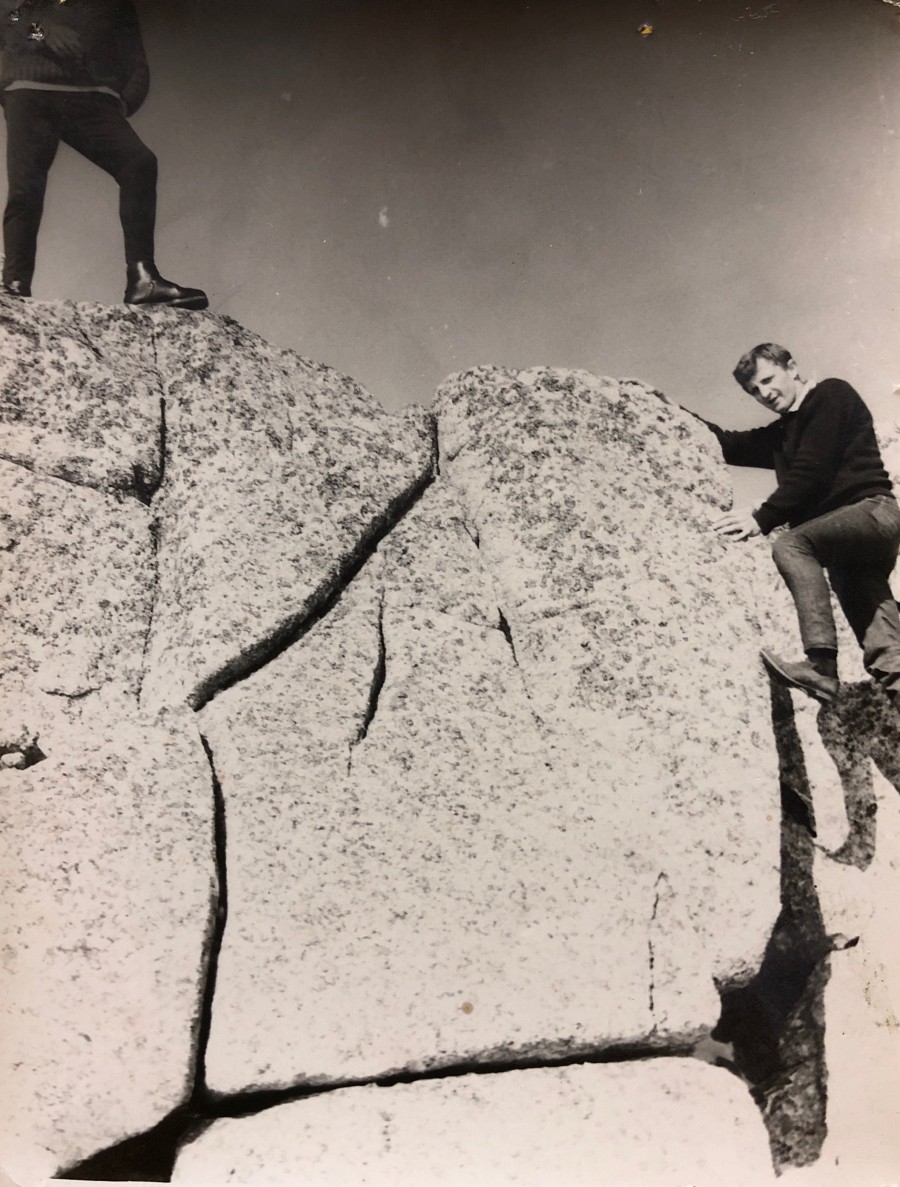

Thredbo

So I left the job within this time and decided I was going to go with a friend to work at Thredbo for a season. In the end, my friend didn't come but I went anyway. I got a job there in what they call 'Bottom Station'. This became a place where we danced all night. We'd then have to back it up and work all day the next day. It's amazing what you can do when you are young. I made some good friends there and it was quite an interesting place.

I saw sights that I had never seen before. My father came down to check to make sure that the staff were reputable. He decided they were. I used to work in the bistro and would do breakfasts. My family nearly fainted with shock by the fact that I got up early in the morning and did that. I'd never had much sleep when I was there. So when I had a day off I used to sleep for nearly the whole day. That then rejuvenated me and I was able to start all over again. But when Dad came down they told him where I was, where I lived and he came back to them and said, "She's not there, she's not answering the door." They laughed and they said, "No you have to go in and shout at her if you want to wake her up." Dad comes back, opens the door and shouts. I got up and then we went down to meet all the friends again.

That was Thredbo. I might tell you that I never skied while I was there. This may have had something to do with having no energy left after working all day and dancing all night. My arrival at Thredbo was famous. I came on a bus from Canberra. As I said my friend chickened out. So when we got to Thredbo I got off the bus and the driver was getting the luggage out. As I got off the bus, I took two steps and fell to my knees. I slid on my knees all the way to the front door because the ground was covered in ice.

Another friend of mine came down there later. She was going out with one of the ski instructors. They got married. They still spend half their life at Thredbo and the other half in Europe.

New Guinea (Part 1)

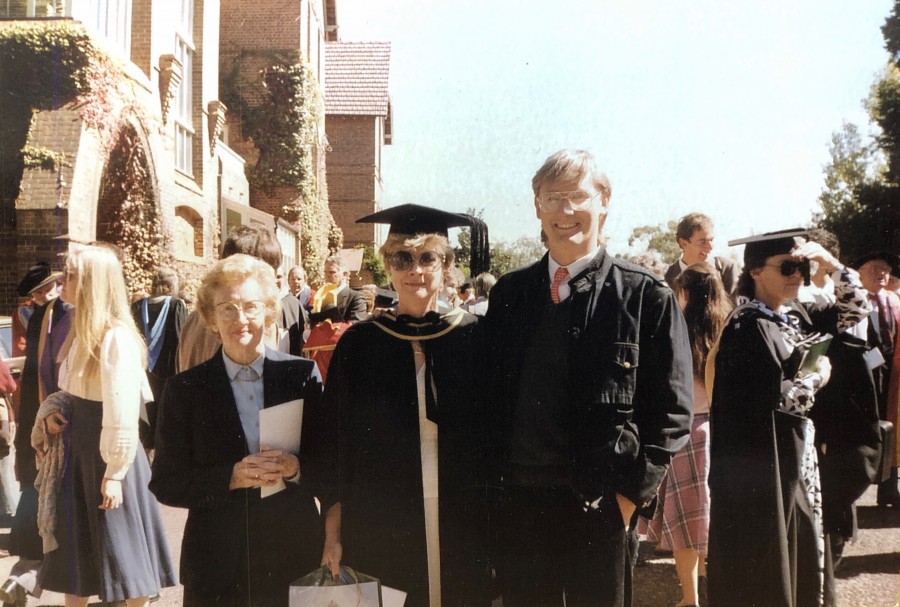

I decided I wanted something more in my life. I wasn’t satisfied with all these funny jobs that I had. So I went back to study at night to get my leaving certificate. My father used to come to pick me up in case I met up with some boy or something. Some of the jobs I had prior to going back to school were: a telephonist, I worked in a shop and I also worked at the post office. But it didn’t matter because to me the main thing was that I got paid. After that I decided I would go to Uni. I got into the University of New England in Armidale. I studied full time, externally. I used to have to travel there twice a year for assessment and treatments and that sort of thing. I remember I lost a book. The lecturer said that it has been returned. I asked the lecturer, “How did you know who it was?” He said, “I remembered it was yours, the sarcastic one.” The rest is history.

After I graduated from University I taught a Stage Three class at Domremy College in Five Dock. I worked there for two years.

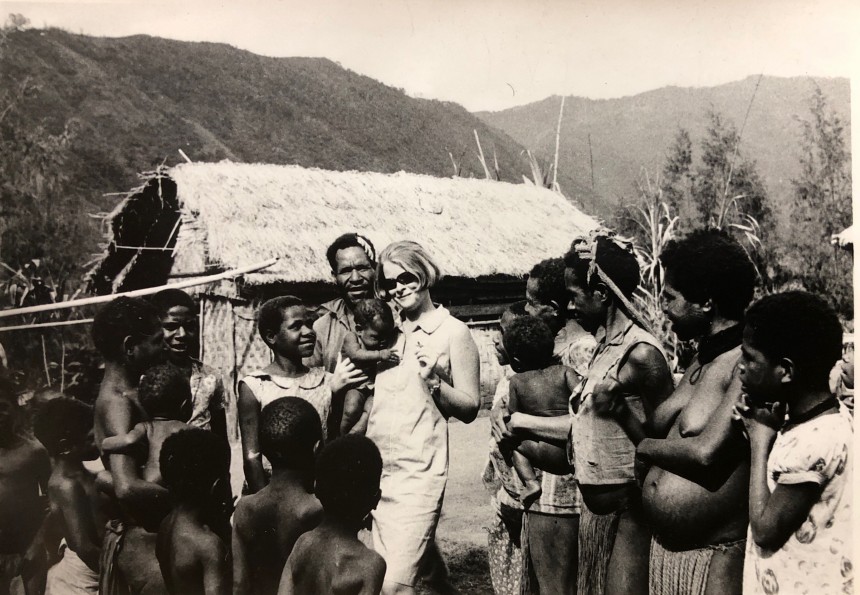

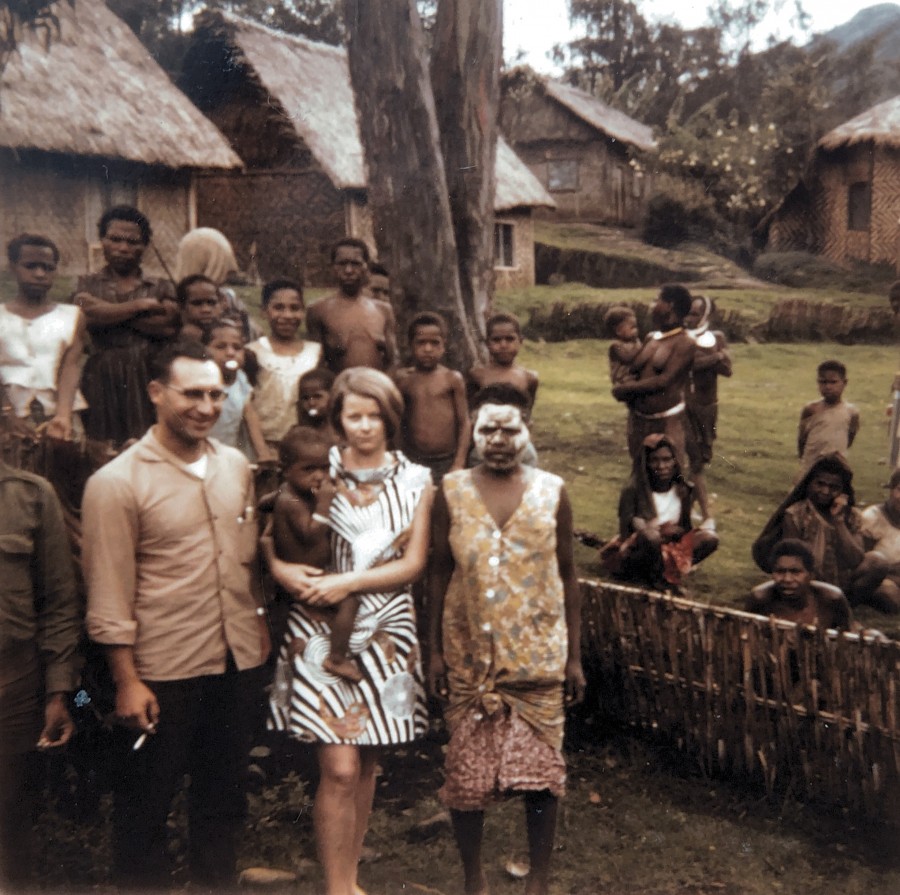

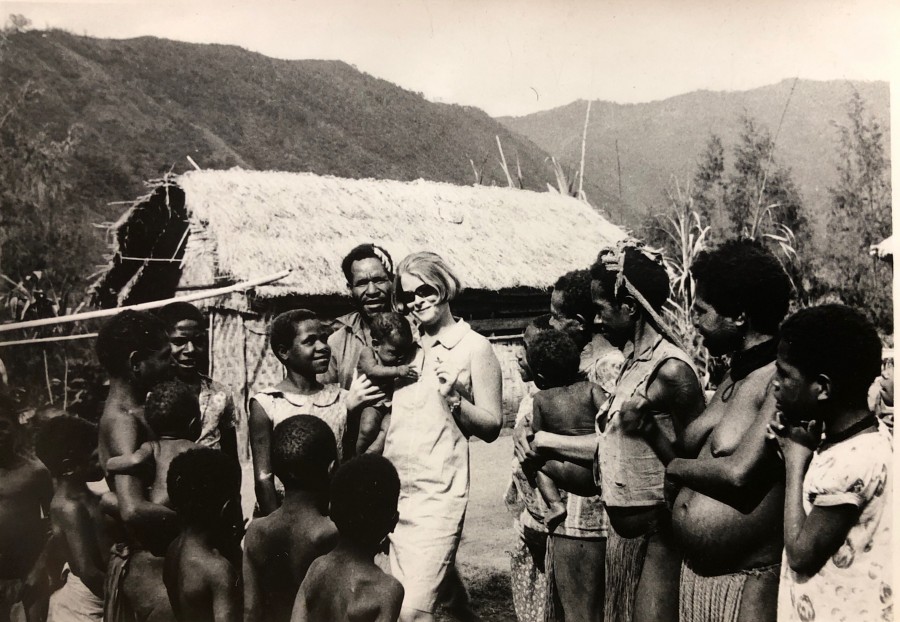

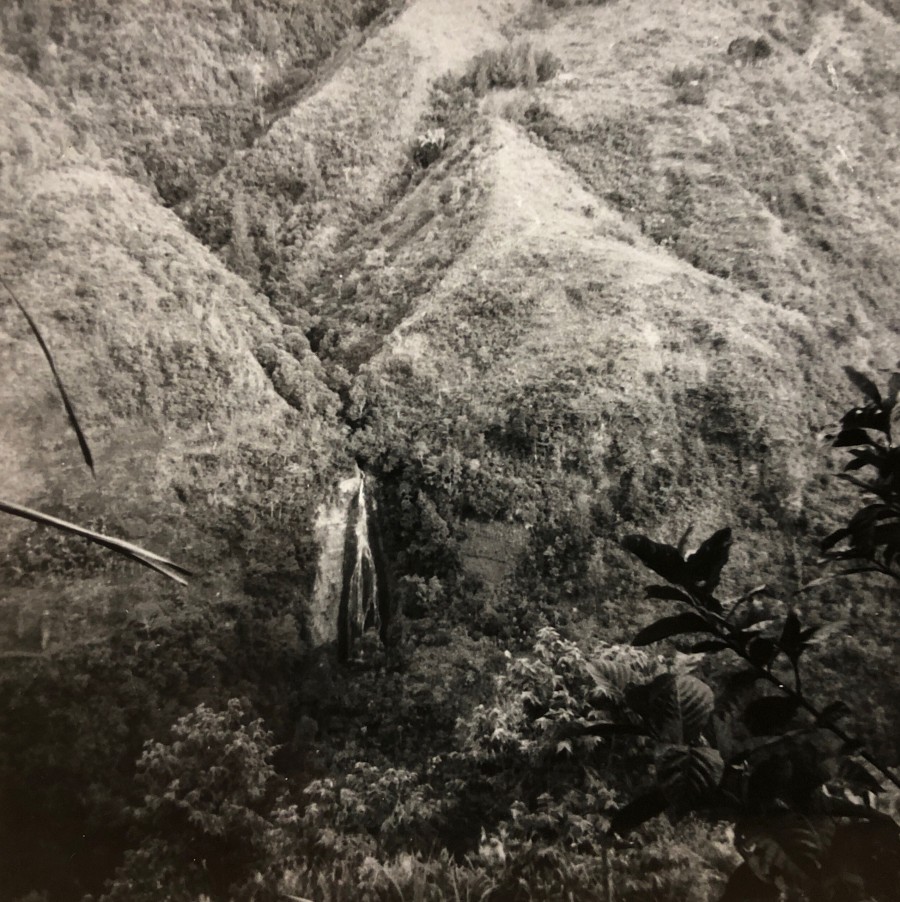

Then that’s when I decided to go to New Guinea. I had seen advertisements for opportunities to go. You had to go to a day where they talk to you about it to see if you were suitable. Anyway, I passed muster. So very quickly I was on my way to New Guinea. It was quite amazing. I had to pack a trunk because I was going for three years. And in it, you had lots of clothing. This was a volunteer position, although I must say that I did get twenty dollars a month for ‘personal needs.’ My mother didn’t say a lot but my father was ropeable. He tried all sorts of things to stop me from going. He said things like, “The family is your responsibility. You should be here to look after them.” I thought, what are you doing here? Anyway, it all happened very quickly and there wasn’t a lot of time for him to work on changing my mind. So off I went. I must say, to be honest, on the plane trip to New Guinea, I suddenly thought to myself, What have you done?

We got to Port Moresby. It was there that I completed a course with the focus being on how to teach students who don’t speak any English.

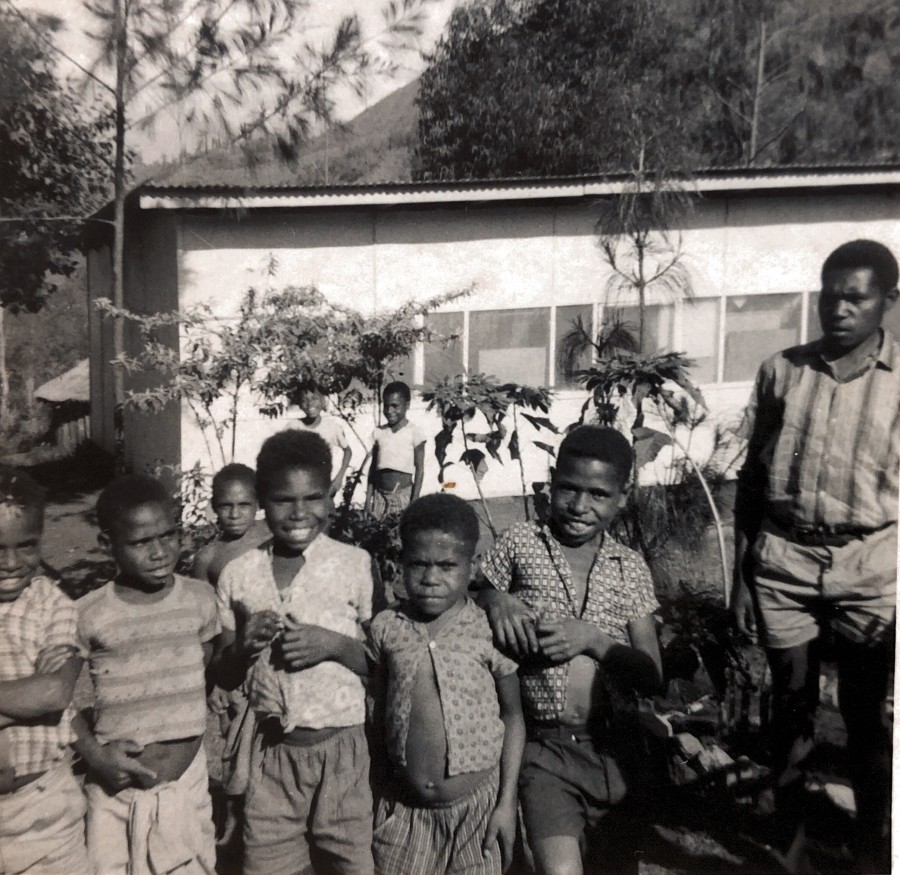

Then I was sent to Goroka. The plane on that connecting flight had no lining and the seats were more like deck chairs. Anyway, we made it safely but the noise was unbelievable. I was taken to a place just outside Goroka. This was a transitioning facility where they decided where you were going to go. To me, one of the horrors of this place was the toilets and showers block. The building was made of corrugated iron and so if you went to the toilet at night, the noise of the cockroaches on the iron was terrifying. I used to have nightmares about the cockroaches and wake everyone up. Apparently, the staff came into my room one night because I was yelling so loudly. When they came in I was tight up against the wall and they said, "What’s wrong?” and I said, “The cockroaches.” They said, “There aren’t any.” And then they woke me.

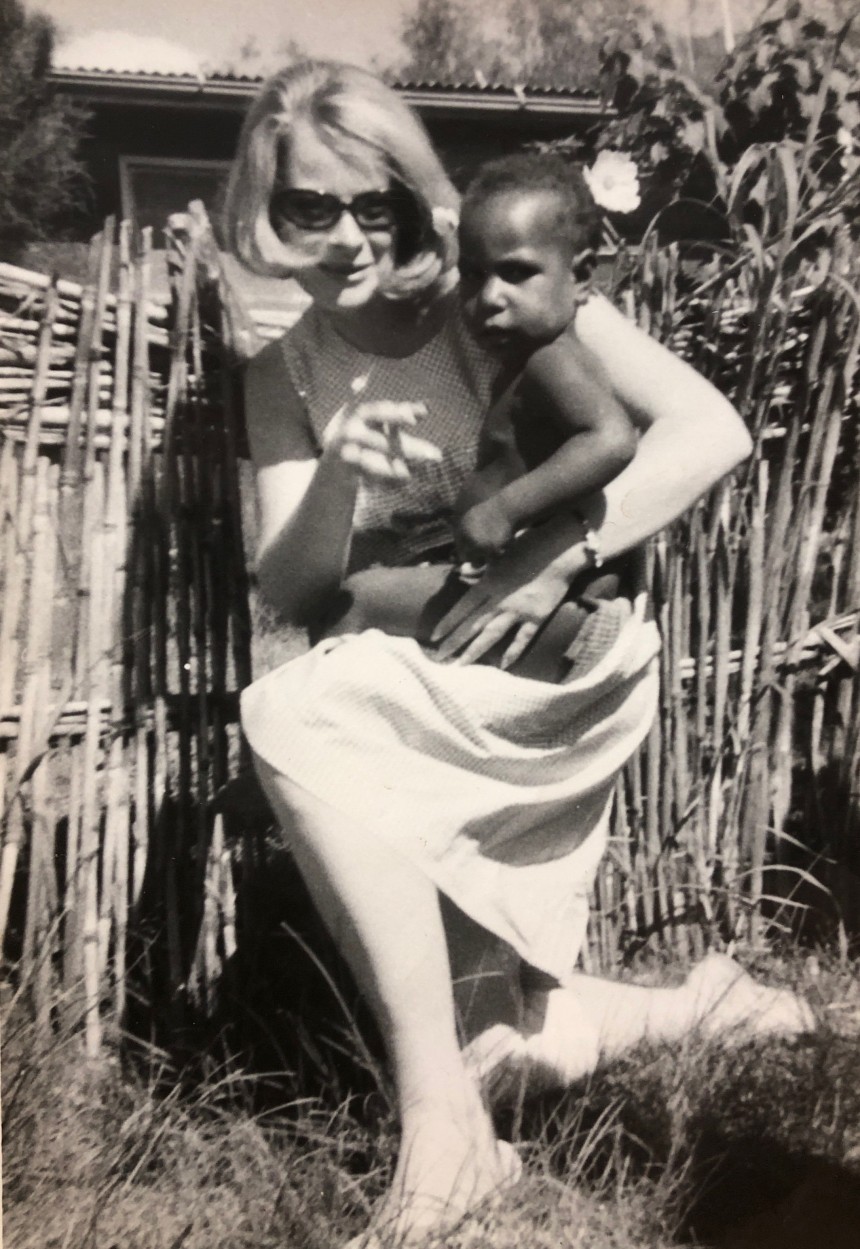

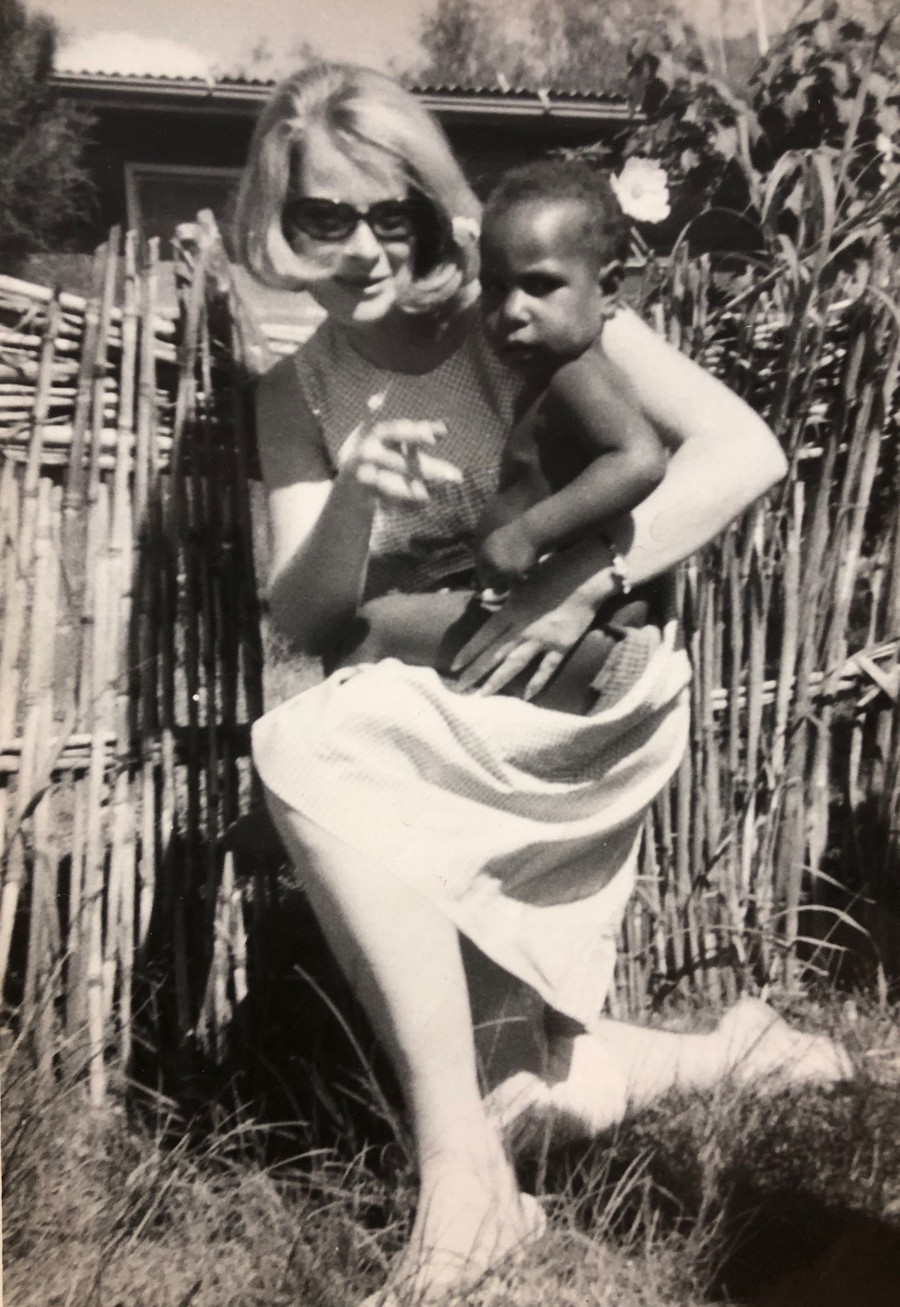

Then I got sent to a place called Yumayufa. I taught there, of course. What I hadn’t anticipated was that there was a heavy nursing component to my duties there. I was amazed at what I discovered I could do. I remember a man came in. He had chopped through his big toe. The only ointment you had was this black ointment. ‘Drawing Ointment’ was what they called it. I slathered that on the toe, wrapped it up and said, “Don’t take the bandage off for a week.”

I used to have to climb mountains to go and see people who were sick. On one occasion, I saved a child’s life. Some people brought a young girl to me. Blood was spurting out of her foot because she’s walked on a broken bottle. I did my best to stop the bleeding but I wasn’t totally successful. So I carried her on my back from where we were to the nearest road. I stopped a truck that was passing by and asked the driver to take her to the hospital. They wouldn’t at first because if someone died and you were with them, the way of things in these parts at the time was that you were deemed responsible. In the end, I got them to take her. I had been too scared to put a tourniquet on in case she ended up losing her foot. So I got the passenger of the truck to hold her foot up. Anyway, she made it to the hospital and she recovered.

After a year in Yamayufa I was sent to Chimbu to set up a school. I had two young men from Rabaul who were assigned to teach with me at the school. So there were the three of us at the school. The local doctor there was called the ‘Doctor Boy.’ He was more of a traditional Papua New Guinean doctor (i.e not a western doctor). All the children seemed to have conjunctivitis. I remember waking up one morning and I couldn’t open my eyes. At this stage, there was another volunteer that travelled and worked with me. She was a very holy person. She spent a lot of time praying. I went to the Doctor Boy to help me with my conjunctivitis. My off-sider was doubtful about his ability to fix my problem but sure enough, he did. There were all kinds of strange things in Chimbu. My off-sider soon left and so I was there, in charge without a guide.

Preparing meals in Chimbu was an interesting experience. Prior to coming to New Guinea I don’t think I had ever cooked anything in my life. I was not that way inclined. I had a small dish that you would pump up and put kerosene in it. You could only cook one thing. I remember this poor priest who was there, came over for dinner. He ate this dish that I prepared. Basically, I had just put every ingredient I had together and we ate that. He said, “Oh that was lovely thank you, Judith.” I thought, No it wasn’t. It was revolting. He was so nice, that poor priest.

A friend of mine from the area went on to become a priest. His name was Ignatius Kilage. We used to write to one another but lost contact over the years.

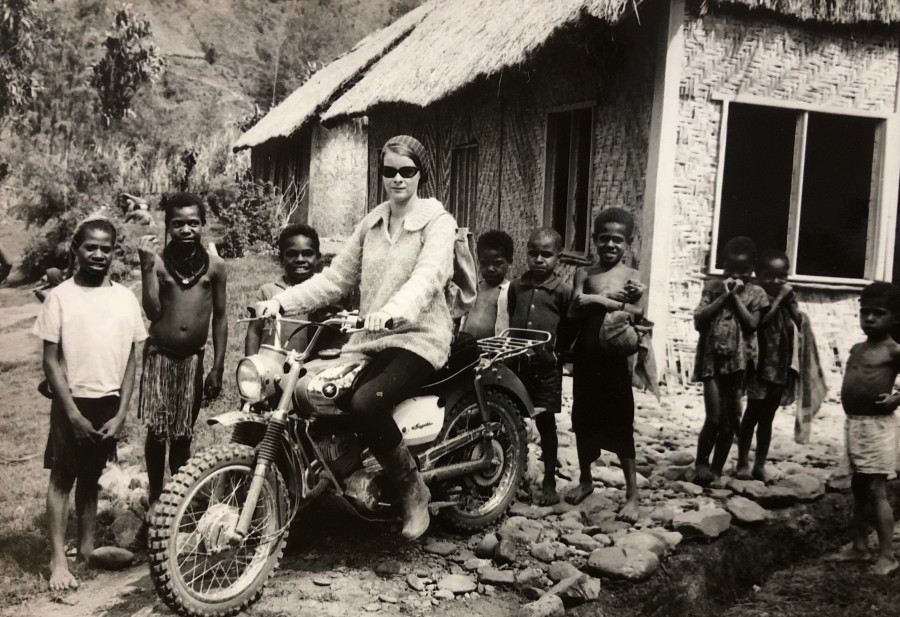

So I was in Chimbu for two years. Most of the time I got on very well with the people. I really wanted to grow vegetables because there were very limited vegetables available to us there. There were no shops there. So I’d grow these vegetables. Then these chickens, owned by the local councillor, would come and eat everything. I got really angry one day. I got the chickens. Put them in a hessian bag and took them on my motorbike into the bush. I let them go. When I got back there was about a thousand people. Half the people were standing there with him and the other half were there to support me. It looked a bit like there could have been a little war. Anyway, he was carrying on at me about taking his chickens. I of course, in my inimitable style said, “Talk finished.” I turned away and he grabbed me by the arm. I backhanded him with my free hand.

Someone must have alerted the local authorities. When speaking to the authorities I asked whether I was going to go to jail for hitting the councillor. He said, “Quite possibly, Judith.” It’s funny because prisoners had to put stones on the roads in order to make the roads. They did this every Monday. I had visions of myself every Monday going out and doing this stone business. Anyway, it all got sorted out. The official said that the councillor had to give me some food and I had to give him a white shirt. They knew that I received boxes of clothes from St Vincent De Paul for the locals. So we met in the garden. I gave him a white shirt, he gave me food and we shook hands and everything was lovely. Those were the days.

Culturally things were very different in Chimbu and more specifically, Womatne, which was the name of the village I was in. Someone had died. There was a funeral. The locals dug a grave for the deceased. But what I noticed was that aside from digging a hole straight down, the diggers also dug down, on an angle. I asked why they did this and I was told that it was so that the dirt didn’t fall on the faces of the departed.

I remember the people there saying to me, “You have to come.” They took me to see a young girl. They told me she had Sanguma. Sanguma refers to black magic or sorcery. Accusations that someone might have Sanguma often come when somebody dies or is ill. To prove it the people told me that the young girl walked past a cow and it died. They had other examples they rattled off, too. So I asked what they were going to do. They said there were two options. The first was to kill her and the second was to banish her from the village. To be banished as an adult would have been bad enough but this little girl was only about four or five years of age. So I’m sitting there and they all looked at me for advice. So I said, “Ok. If she can make me sick, she’s got Sanguma.” The people were all screaming and crying. Anyway, thank God I didn’t get sick and the girl was ok.

Once I was teaching a Religion lesson about the Miracles of Jesus. One of the children in my class said, “There’s a man in our village who does that.” So I didn’t waste my time talking about miracles again.

All the other Westerners there were Germans. I didn’t know that the German priest was there. One of the students in my class asked, “Can we say God bless you to the Lutherans?” I said, “Of course you can. God loves all people.” Afterwards, the local Catholic priest cornered me and he said, “You should have added that to be Catholic was better.” I said, “I’m not starting religious wars here, thank you.” It was lucky that I was always a forthright person. Otherwise, I don’t know what would have happened. This same priest was a quirky fellow. If the spark plugs on his motorbike weren’t working, he’d just take mine.

Most of the priests were either from Germany or the United States. The Lutherans, who weren’t far from me, were from Ohio in the United States. Their names were Norm and Wanda. I used to keep an eye on their school to see what was being done. They would invite me over for dinner. Norm and Wanda were very nice people.

New Guinea (Part 2)

One of the things that happen to you when you are nowhere near your ordinary civilization is you become rather superstitious yourself. One very strange thing happened. I was going to Gogelme one evening. My motorbike broke down on the main road. It was a moonless night – pitch black. I started to walk. All of a sudden, a man appeared with a lantern. He said, “Abenoon Mrs.” He asked if I was going to Gogelme and I told him I was. He said, “I’ll light the way for you.” So we walked together and as we approached Gogelme, he seemed to disappear. I couldn’t work out where he had gone. After school each day, I ran classes for teenagers who never had schooling in their younger years. I taught them Pigeon English and Crop Rotation. Anyway, the day after this strange evening, when I sat down with these older students, they said, “You walked to Golgeme last night.” I confirmed this. They said that the man who I met on my way saw me walk past his house and he was worried about me. Very soon after this, the man died. I was shocked and I thought Oh no I’m going to get the blame, which was often the way of things there at the time. So they said that he had already passed away and the figure who came to light the way for me was his ghost.

There were a lot of strange things that went on. I remember there was a river coming down. It was overflowing. There had been a lot of rain up in the mountains. The local people were doing things to protect their places. As I walked along I said to a family, “You ‘re ready for anything aren’t you?” They had both Christian and native paraphernalia all around the outside of the house, to keep them safe.

The people there were very good to me. On Mondays, they used to bring me food. Always on top of the food was a packet of gold leaf cigarettes. The thing was that someone had to have paid for them because this wasn’t provided by St Vincent’s De Paul.

At the trade store, you could buy two things: matches and kerosene. That’s all. I’d get bread from Dengelagu. It was a type of German bread. If you didn’t eat it quickly, it became so hard, you could knock people unconscious with it.

When my three years was up I went home. When I got home it was quite strange. Mum and Dad took me to the Theatre. I had to go outside because I couldn’t cope with the perfumed smells of the people. They took me to dinner. I’d only eaten meat about twice in the three years I was away. I ordered Steak Dianne. Then the waiter came to take my order for dessert. I ordered another Steak Dianne for dessert. It was a bit hard when I came home. I went back to teaching at Domremy. I continued to teach there for two years.

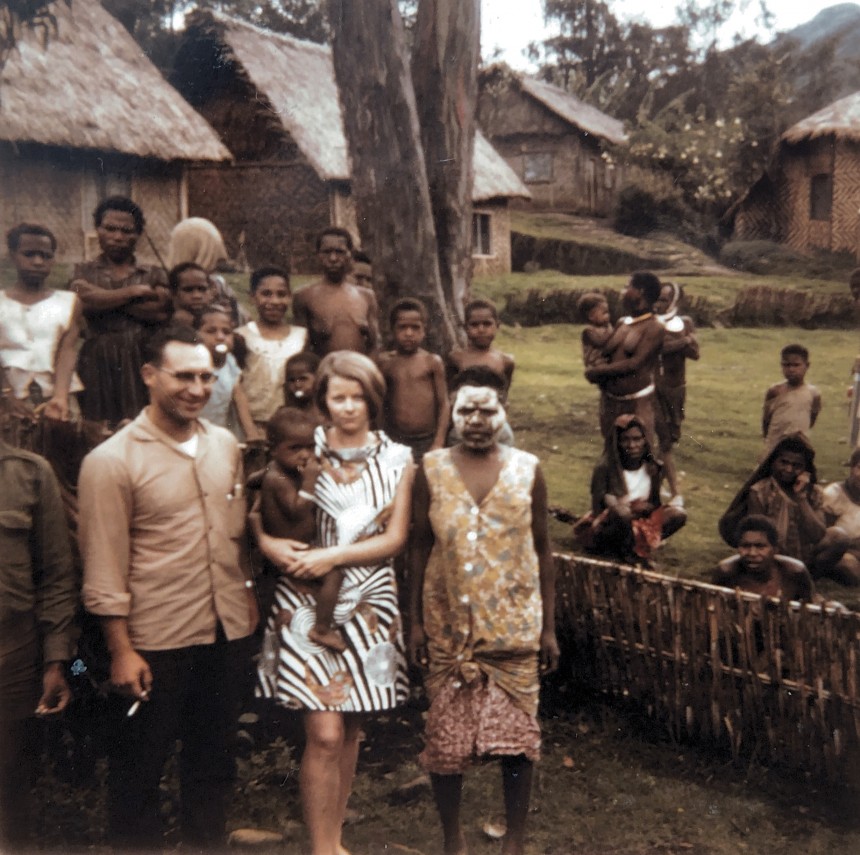

In 1971, I went back to New Guinea. This time I was up at Dengalagu, which is right up in the mountains. In Dengalagu, all of the Westerners were Germans. There was one particularly disagreeable man who made a comment about my skirt being too short. I told him that it wasn’t short and that back home, women wore their skirts considerably shorter. “You’re all prostitutes,” he said. I approached Father Lawsy to complain about this fellow. He defended the man saying that he didn’t speak very good English. “Prostitute’s the same in any language!” I fired back.

When I asked Father Lawsy for permission to try new things at the school, he always said no. Pretty soon, I stopped asking and would just go ahead and do what I needed to. One day he said to me, “Judith are you sure you don’t have German blood?” I told him that I didn’t but asked why he’d ask such a question. He said, “Because you’re so stubborn.”

There was a woman there by the name of Waltraud and she worked in the laundry. I lived in a place that had a dirt floor. Somehow my sheets fell on the floor. I took them up to the laundry to be washed. Well did Waltraud abuse me? I said, “Well you have proper floors in your place.” Another lady by the name of Gertrude worked there. She was a very holy woman. She said, “Judith, blessed are the peacemakers.” And I said, “And you can shut up too!”

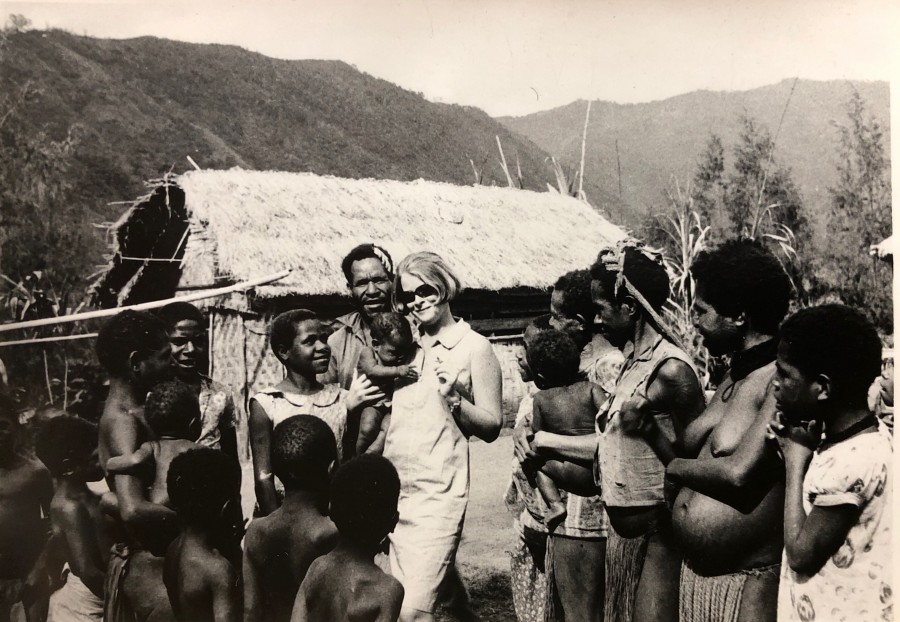

One of the sad things about that time though was that even though the children I taught did very well in their exams and gained entry into a good high school, the students didn’t last long there. The high school was on the coast. I think my kids felt as though they didn’t fit in. It may have had something to do with the fact that people from Chimbu are quite short.

Another thing I did was when there were public holidays, I ignored them and just had school as normal. I then added the day onto the school holidays. This gave the teachers more time to go home and see their families in the holidays. This was fine until of course I got caught. We were all in school one day and the local officer turned up and asked, “Why are you all in school? It’s Anzac Day.”

The children couldn’t speak English when I arrived. By the end of a year with me, they could speak quite a bit of English. The problem was, however, that they talked just like me. They had my Australian accent. The children at the Lutheran school spoke with an American accent.

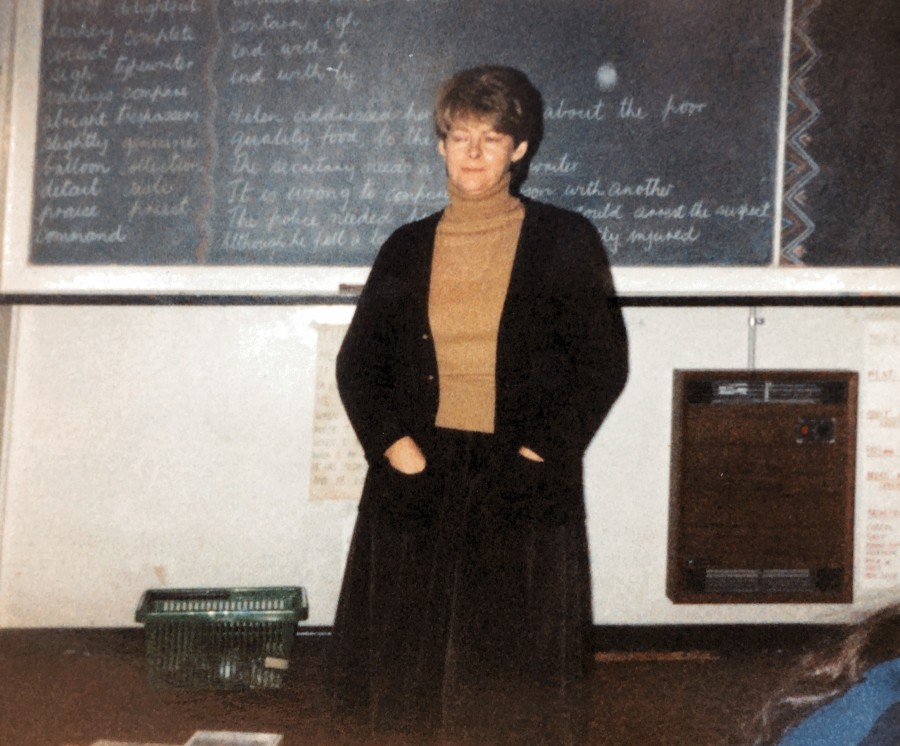

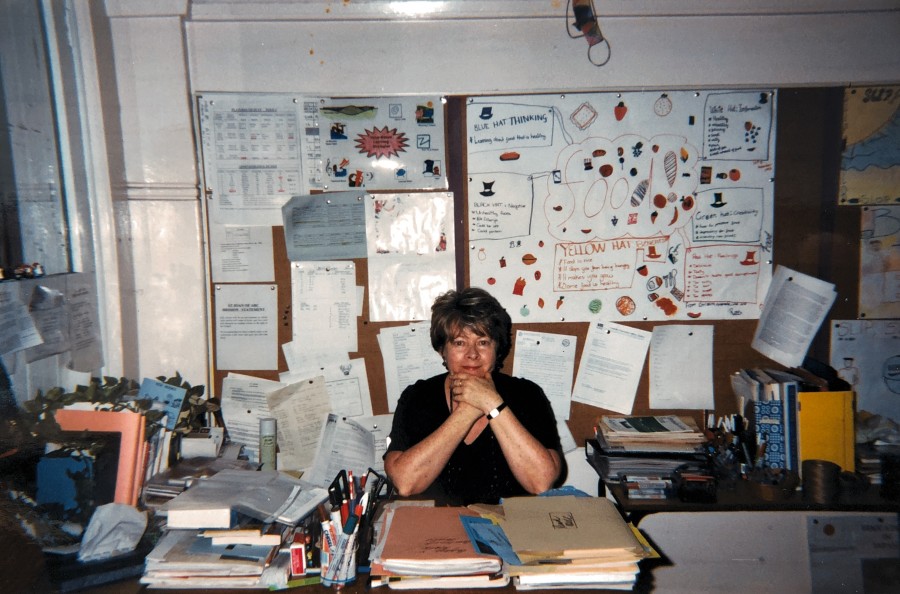

Teaching

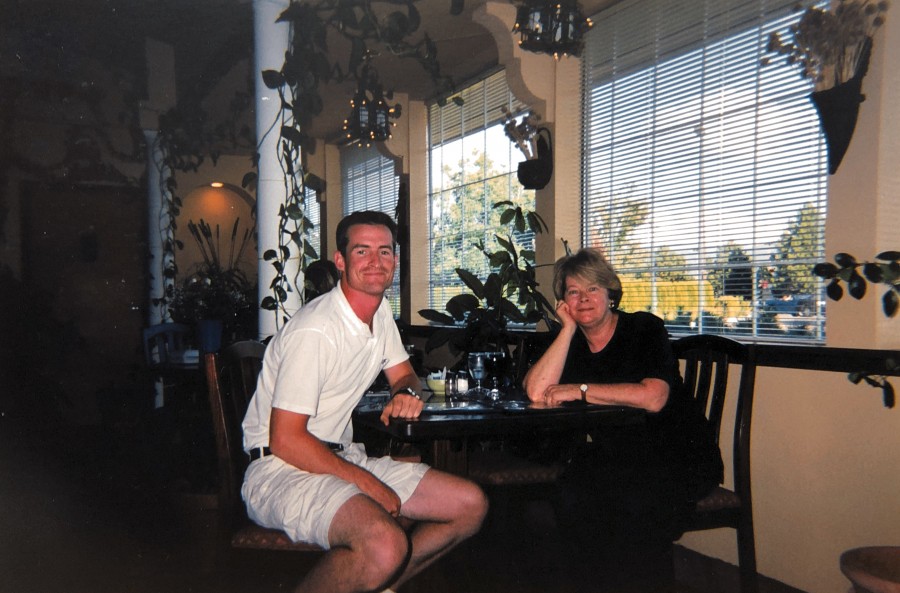

In 1973 when I arrived back in Sydney from Papua New Guinea, we were invited to a PaIms evening in Haberfield. Mum came with me. I stayed for about three minutes and then I left. They spoke to Mum and said, “See if you can find her and get her to come back because if she doesn’t settle...” Anyway, whatever did happen, I did settle.

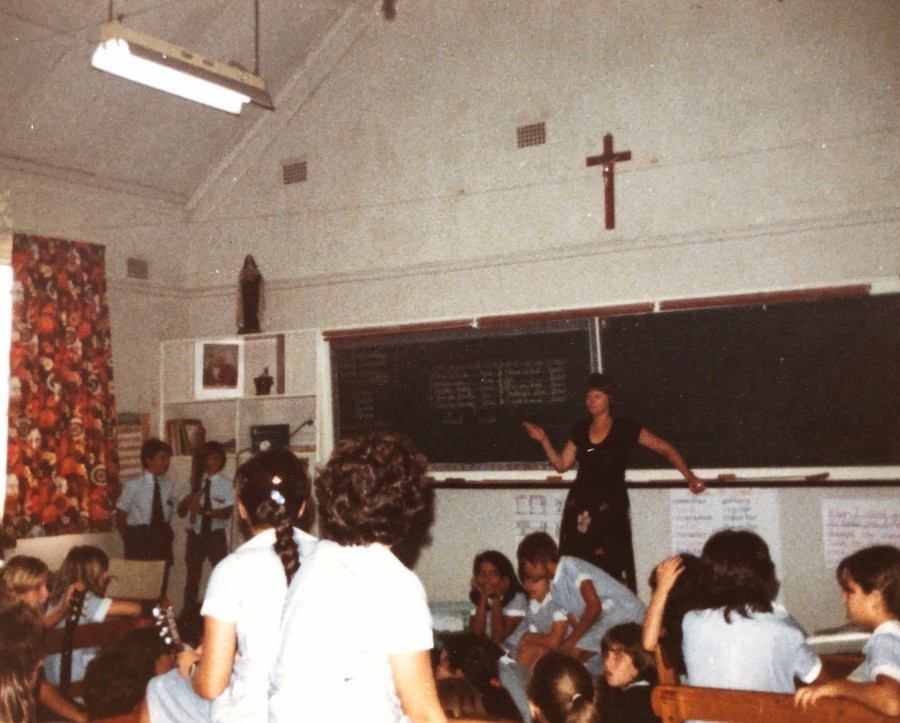

Sister Roberta was the Principal at St Joan of Arc. It was she who gave me the job at St Joan of Arc.

There were a couple of nuns at the school but the rest were just teachers like me. So I seemed to be, for a while anyway, only on Year 4. Later on, I’d teach year 5 and 6. Only once did I teach younger children, when I had a year 3 class. It was quite an adjustment having just come from teaching year 6. I remember filling the blackboard with words and the students came in and said, “We can’t read it.”

So I taught at St Joan of Arc for years. There was one occasion where I taught a Year 4 class at the Catholic School in Meadowbank. Principals changed over time at St Joan of Arc. I made good friends with my teaching colleagues and had wonderful relationships with families in the community. The local Italian parents would say, “You are making them learn.”

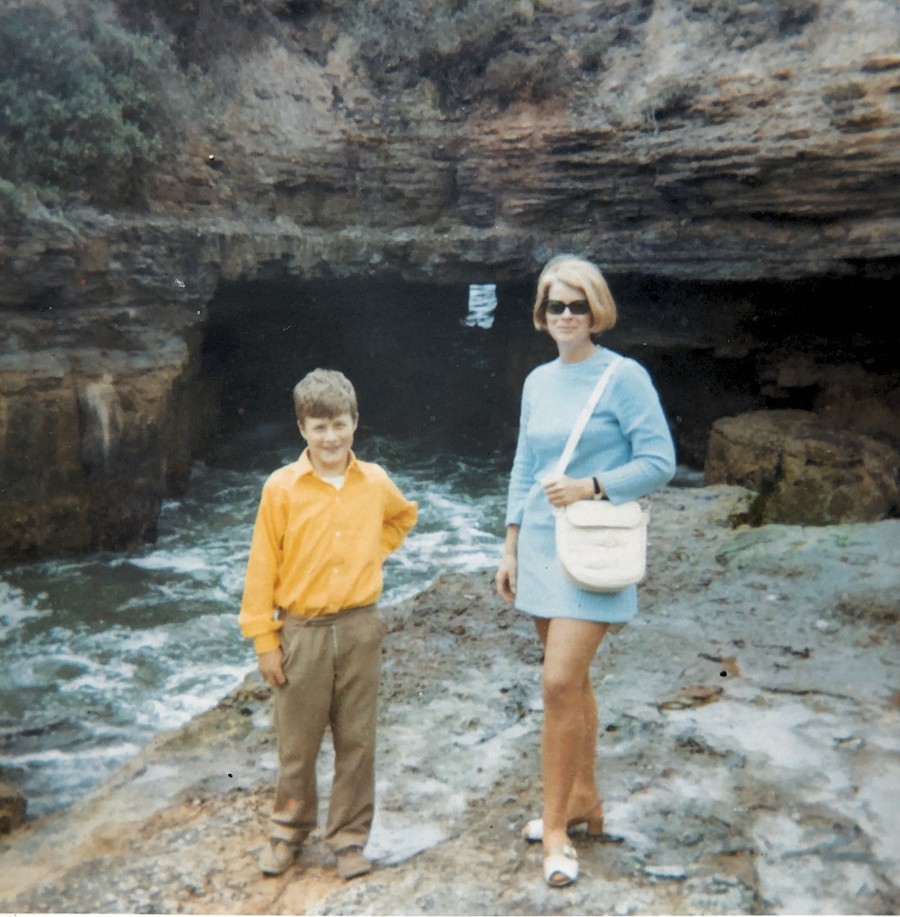

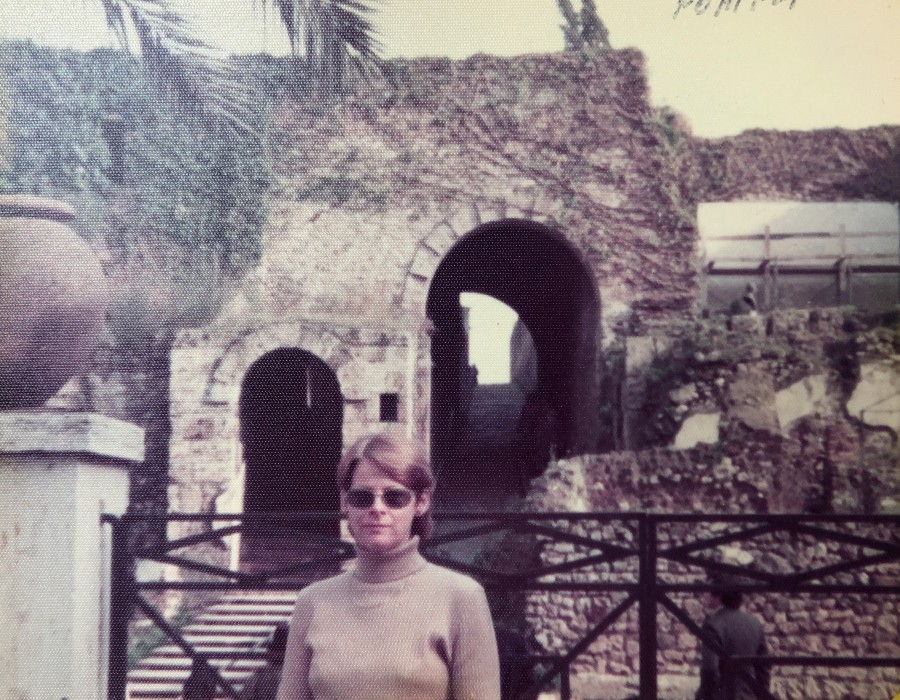

My Travels

After I had been working a while I decided I wanted a holiday. Because I didn’t have any long service leave, I had to go in the Christmas Holidays. I went to London. Mum knew someone in London who ran a Bed and Breakfast so I stayed there. Then I went up to Dundee in Scotland because that’s where my maternal grandfather came from. I visited the street where my grandfather used to live. One side of the street had been demolished. He lived in a large building with a corridor all the way through. Each room had a family in it. You had to go out the back to find a toilet. They used to wash at public wash houses that they had. I spent a few days there. I stayed in a bed and breakfast place that had a bar and I met all sorts of people. I also spent some time with Mrs Tolhurst's family. On New Years I got invited to several parties. Someone came to me and said, “Have you got a long dress.” I said, Yes.” They said, "Good." You can come to the party.” I’ve never seen so many drunk people in my life.

So then I had to get back to London because I was joining up with a tour.

On the tour we went to Paris. We were taken to a show in Paris. I’ve never seen so many naked people in my life.

We went to Switzerland which is a place which looks as beautiful as it does in photos and calendars.

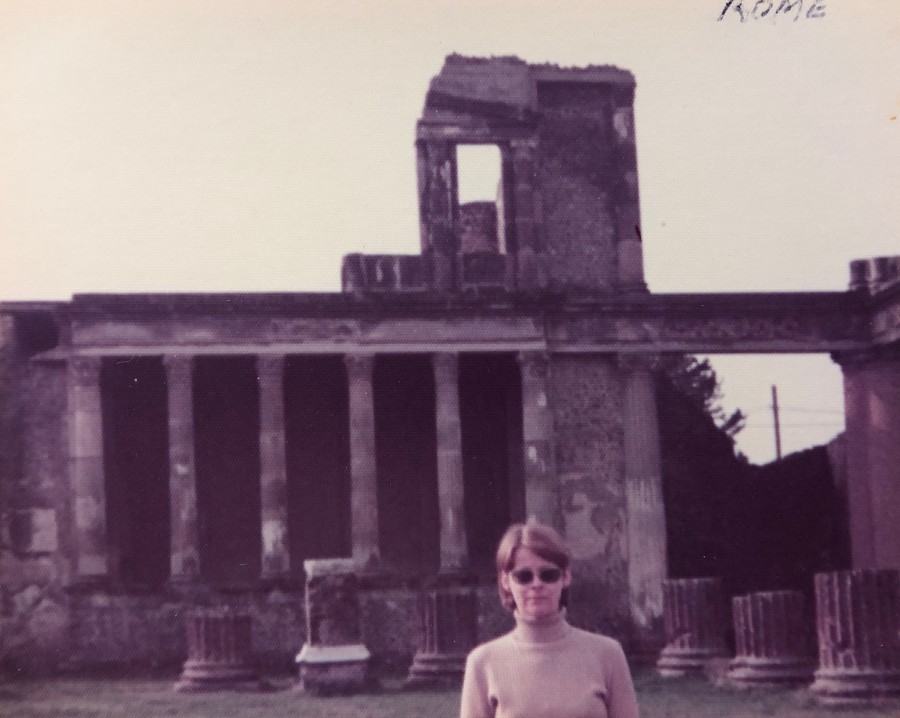

We went to Italy. I saw Venice while we were there. When we were in Rome, a man on the street pinched me on the bottom. We saw the Sistine Chapel in Rome. To get a good view, we laid on the floor and looked up at the ceiling.

The tour took in Germany. I remember being at a coffee shop in Munich. Everyone was so dressed up and most people had a dog sitting next to them. I’d never come across that before. I went to Poland, Warsaw and Krakow.

A few years later, I had long service leave. I did quite a big trip. I went to Athens first and wandered around there. One of the things that fascinated me was on the Plaka there’s different little churches. They’re all to do with Guilds. There was even one for the tax collectors. Then I joined this bus that went up to the north of Greece. I went up to Thesaloniki. John’s uncle said, “Oh I wish I’d known, that’s where I came from."

We travelled up further into the mountains. From there we travelled to Sofia. In Sofia there’s a huge cathedral named Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. What the people told us was that when the communists came, they dug the ground and buried all of the accoutrements from the church. So now they were digging it up. Then I walked down another street and came to another street. All of the churches have paintings on every wall. It was when leaving another church, a gypsy grabbed my arm. I said, “Let me go or I’ll call the police.” She let me go. It was here in Sofia that I did a lot of my shopping for family back home. Then I travelled through to Romania.

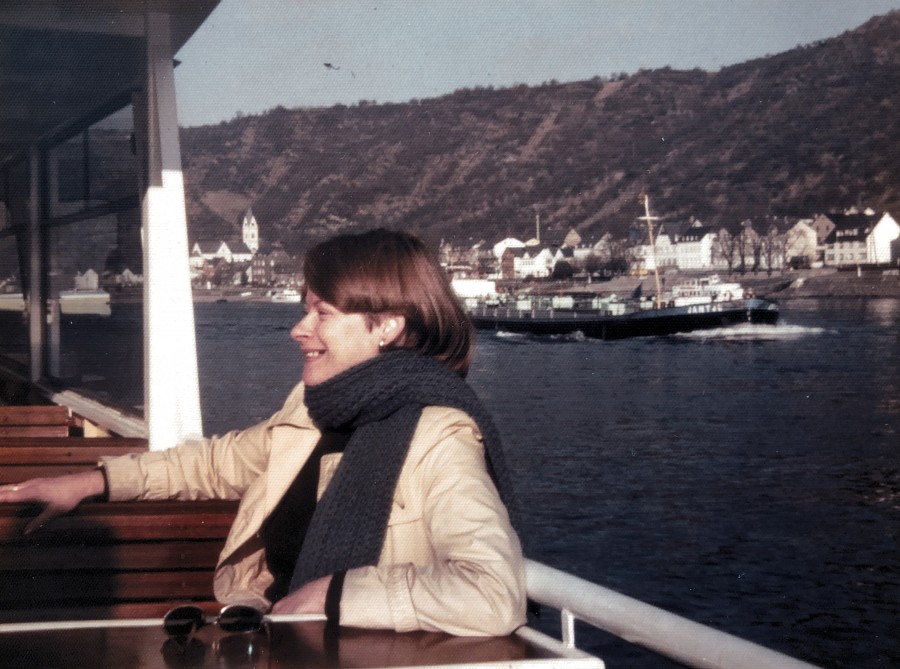

We went down the Reine and then we went to Heidelberg. It was good fun.

On one trip I was in Austria. I travelled through Vienna. I went to Auschwitz but I didn’t go in. I couldn’t. When I was in Germany, everyone conversed with me in German. I think they thought I looked German. Quite recently Vanessa got me a DNA kit to track my origins. What I discovered was that I’m predominantly Celtic, with a mix of Irish and Scottish. It seems as though I have more relatives in Scotland than Ireland though. It also turns out that a small percentage of my DNA comes from Northern Europe. Probably a bit of Viking.

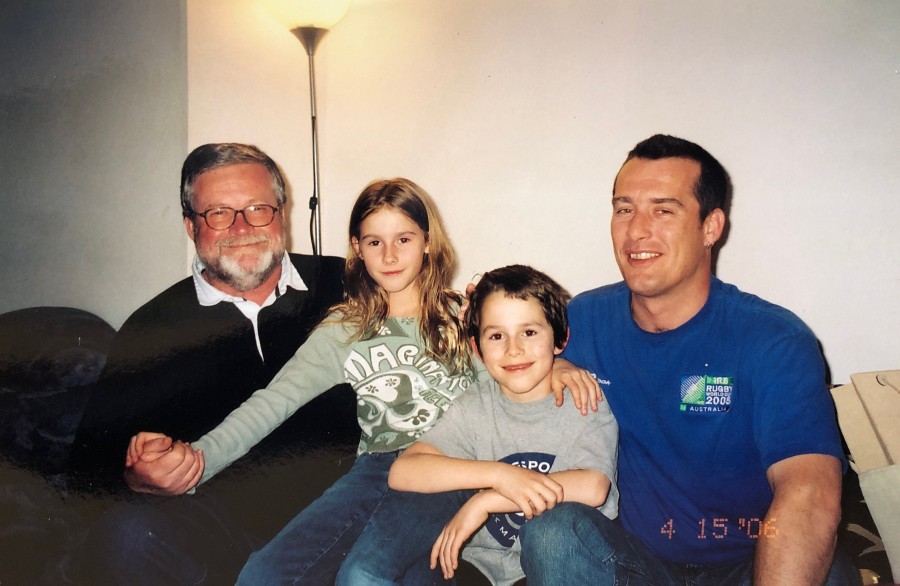

From Vienna, I flew to Montreal in Canada. I went there because Patrick, my nephew, was living there at the time. He and Abigail (his daughter) picked me up from the airport. So I spent some time with them.

Then I went to Niagara Falls. When going to Niagara Falls from Canada, you step into America. When checking my passport at the border, the passport inspector asked me, “Where are you from?” "Australia I replied." “But this is an Irish name,” he responded. “Yes but I’m still from Australia and that’s where I live,” I said.

I’ve been to Hawaii. I went there by myself. I couldn’t believe how cheap it was to travel around on a bus.

My Parents

Mum and Dad were always very fond of each other. They spent a lot of time talking. I remember one night they went out somewhere and Dad came home and I said, "Where's Mum?" And he said, "Isn't she home?" I said, "No." A little while later she turned up and it turned out that either she or Dad had danced with someone else and the other one was cross about it. So they had to make up when they got home. But they seemed to be always very fond of each other. Except, that is when there were elections on. The only times I can remember them arguing were when there were elections. This was due to the fact that they supported different parties. Surprisingly, my mother who grew up in a house where money was never a problem or anything, always voted Labor. My father, who grew up in a household that was quite poor, was a Liberal voter. So that was the only thing they ever argued about. They never changed their allegiance to their political parties.

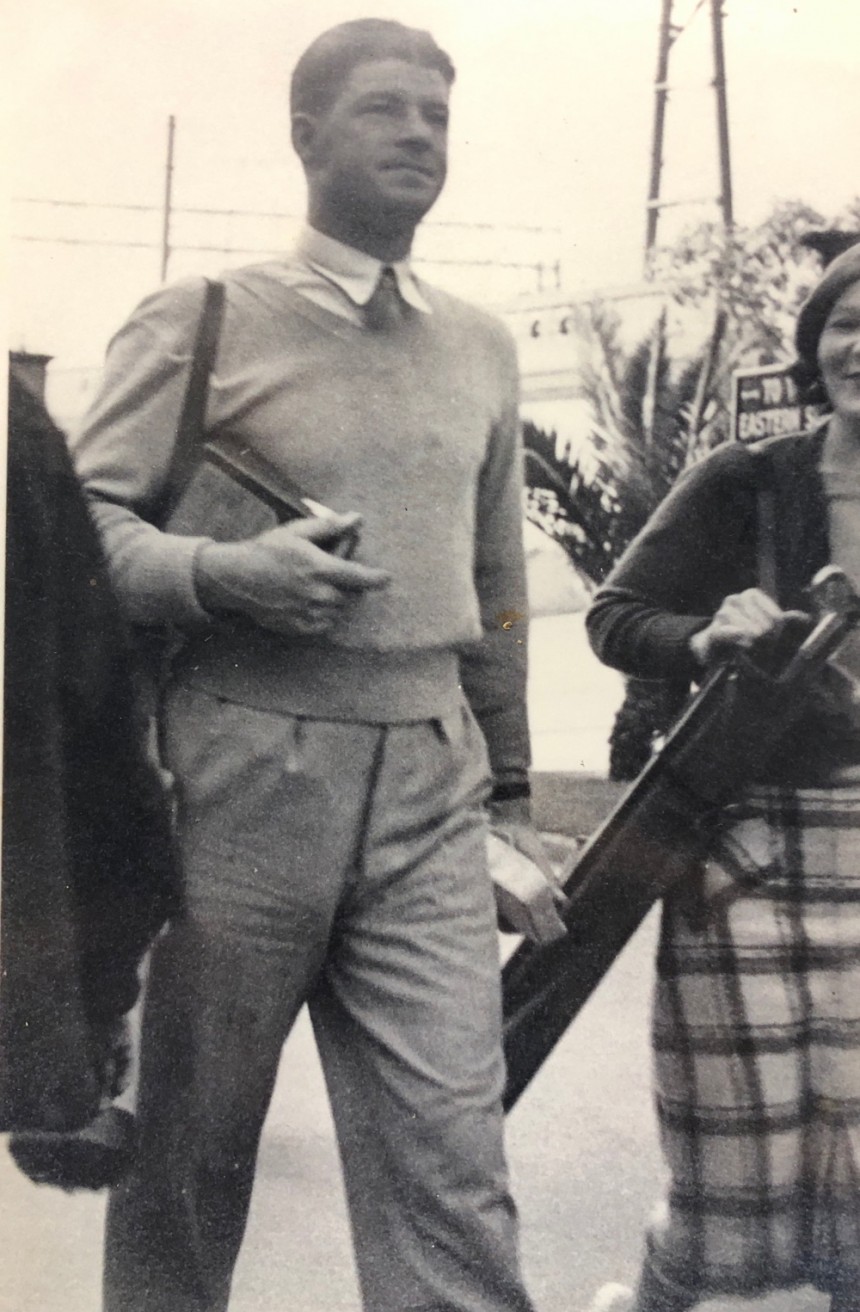

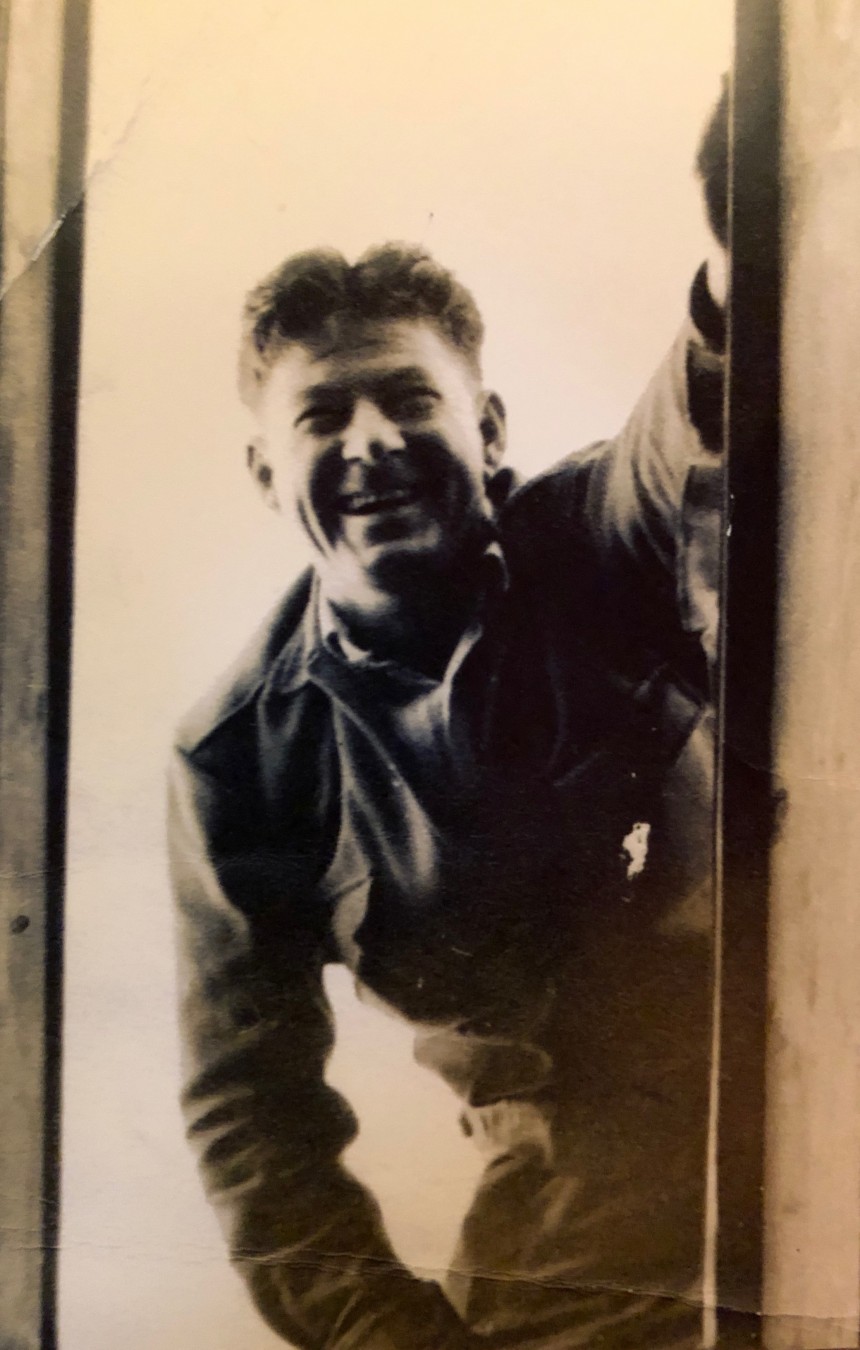

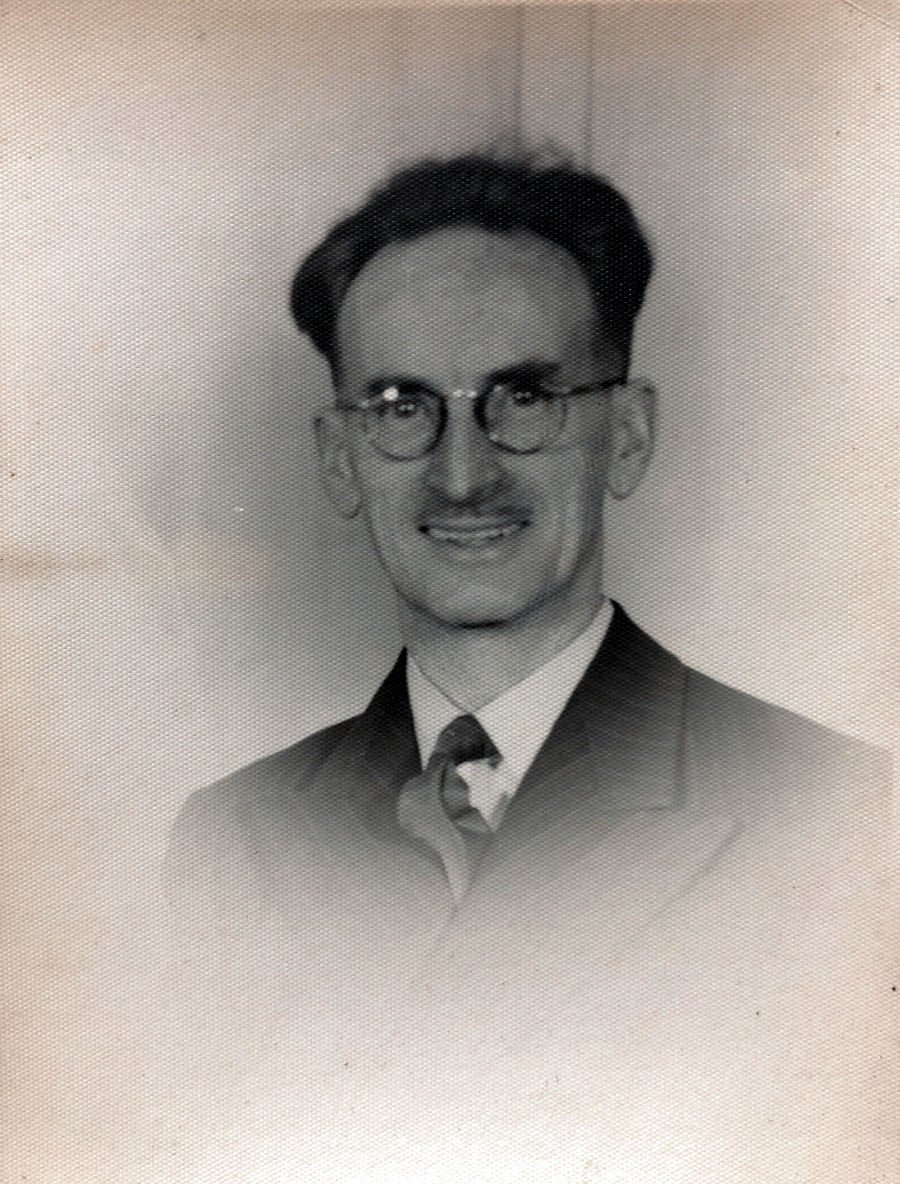

My Father

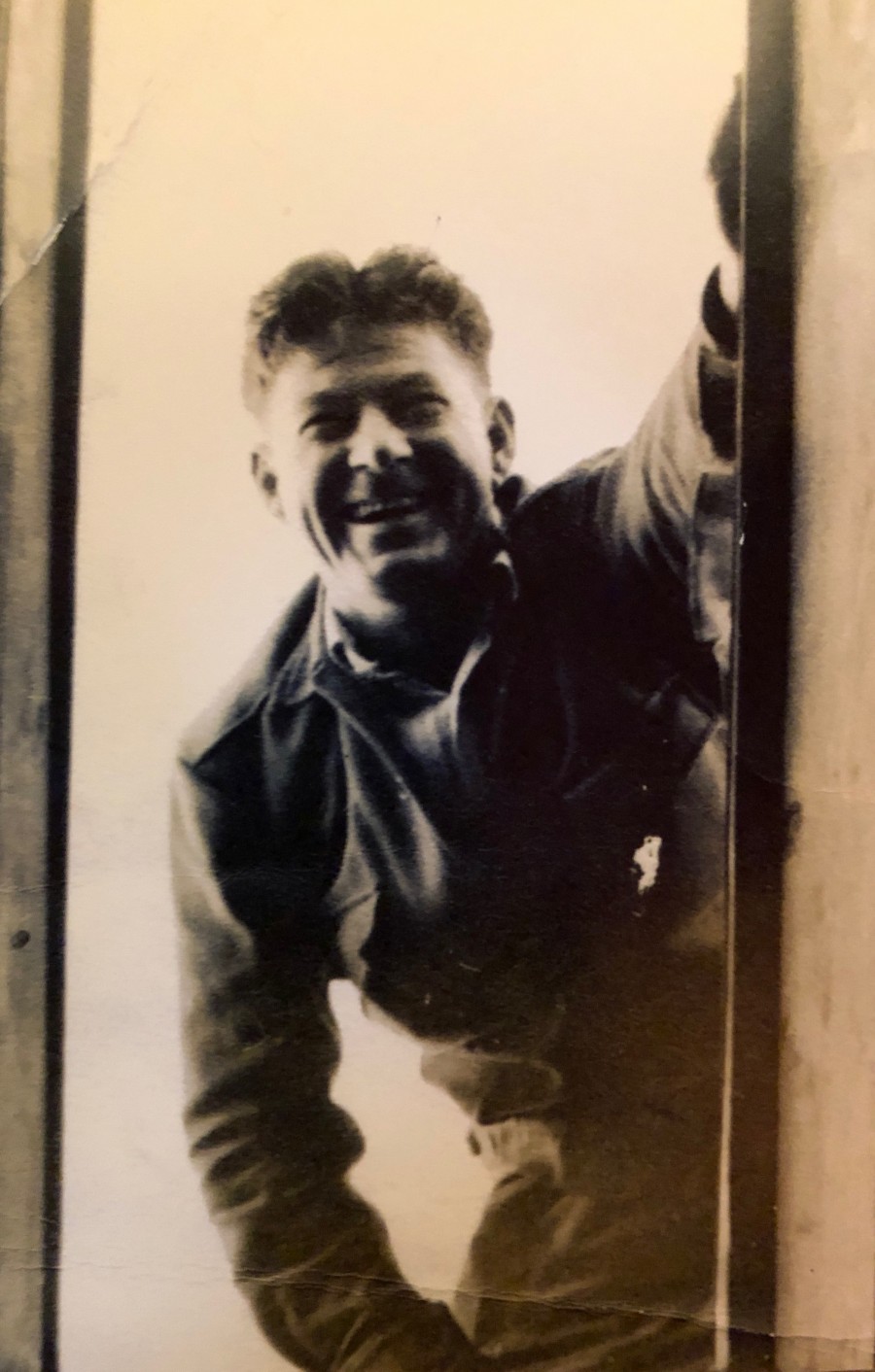

My father grew up in the Eastern Suburbs and in Penshurst.

In 1939 or 1940, he had gone to volunteer to go to the war. Dad failed the medical. Not only did he fail the medical, because they said he had such high blood pressure, but they put him straight into hospital. The sergeant said, "We like them to live to reach the front." So of course obviously he didn't go to war.

Dad learned a trade. He was a plumber, gas fitter and drainer or whatever they call them. He did that and he worked with another man. He was working in his own business and he had some apprentices at various stages. This was in Ramsay Street. One of his apprentices was a Spanish fellow who'd left Spain to get away from Franco and the civil war that was happening in Spain at the time. Another apprentice was Mr Darby, an older fellow, hence we called him Mr Darby.

We had a big yard. I remember Dad was able to spread out all the guttering and everything. In the laundry, Dad had put a shower in so that when we came home from the beach we could just wash all the sand off ourselves. One day I slipped and hit my head in the laundry and so my father, never doing things by half measure, removed the shower from the laundry.

If we fought over anything, my father just took it away. So there was never a chance of getting it back because he’d just take it away for good, if you fought. When we were a bit older we used to go to the movies on Saturday afternoon. We'd see movies like Batman, and lots of cowboy films. You'd go to that and at interval, you would get some chips and an icy slice. An icy slice had two pieces of wafer with some ice cream in the middle. So that was Saturdays. And by the time I was 12, I was looking after children and even a baby. Anyway, I seemed to be quite capable of lots of things. If we were really naughty through the week Dad would say, "No movie." On a Saturday, he'd come home from work and we'd all be playing. He’d say, "Why aren't you at the movies?" And I'd say, "Cause you told us we couldn't go." So then he was lumbered with us all being in the yard.

He had a lot of funny ways. Tony seemed to have the knack of annoying him. I remember going crook on Tony once. I said, "Keep your mouth closed." As a matter of fact one of the things I said was, "If you can't lie properly, don't say anything."

I remember I was allowed to go to a dance at Ashfield of a Saturday as long as Tony came with me. So we'd walk up to the shops in Haberfield. I'd get the bus and he'd go somewhere else. I think he went and played snooker or something. It all worked well because my bus got back around the same time as Tony's and then we'd just walk home together. One time Tony wasn't there when my bus got back. So I waited for him and we got home quite late. When we went home we could hear movement. Fearing trouble for being so late, I just got into bed, fully clothed and pulled the blankets up to my neck. But Tony was slower than me so he got caught. Dad carried on. Then he walked past my room and he said, "And I know you're fully clothed in there."

We were all a bit scared of him. He was quite dramatic, himself. The lay missionary people thought my father was really funny. And I used to think, what is wrong with you people? When I came back to Australia after three years in New Guinea, Dad was at the airport to pick me up. There were a lot of the bigwigs from the Catholic Education Office there, to welcome us volunteers back. The passengers were exiting the plane and our group from New Guinea were the last to get off. Dad called out to some of the airline staff, "Do you make them fly with the cargo, do you?" The representatives from the Catholic Education Office thought this was quite funny.

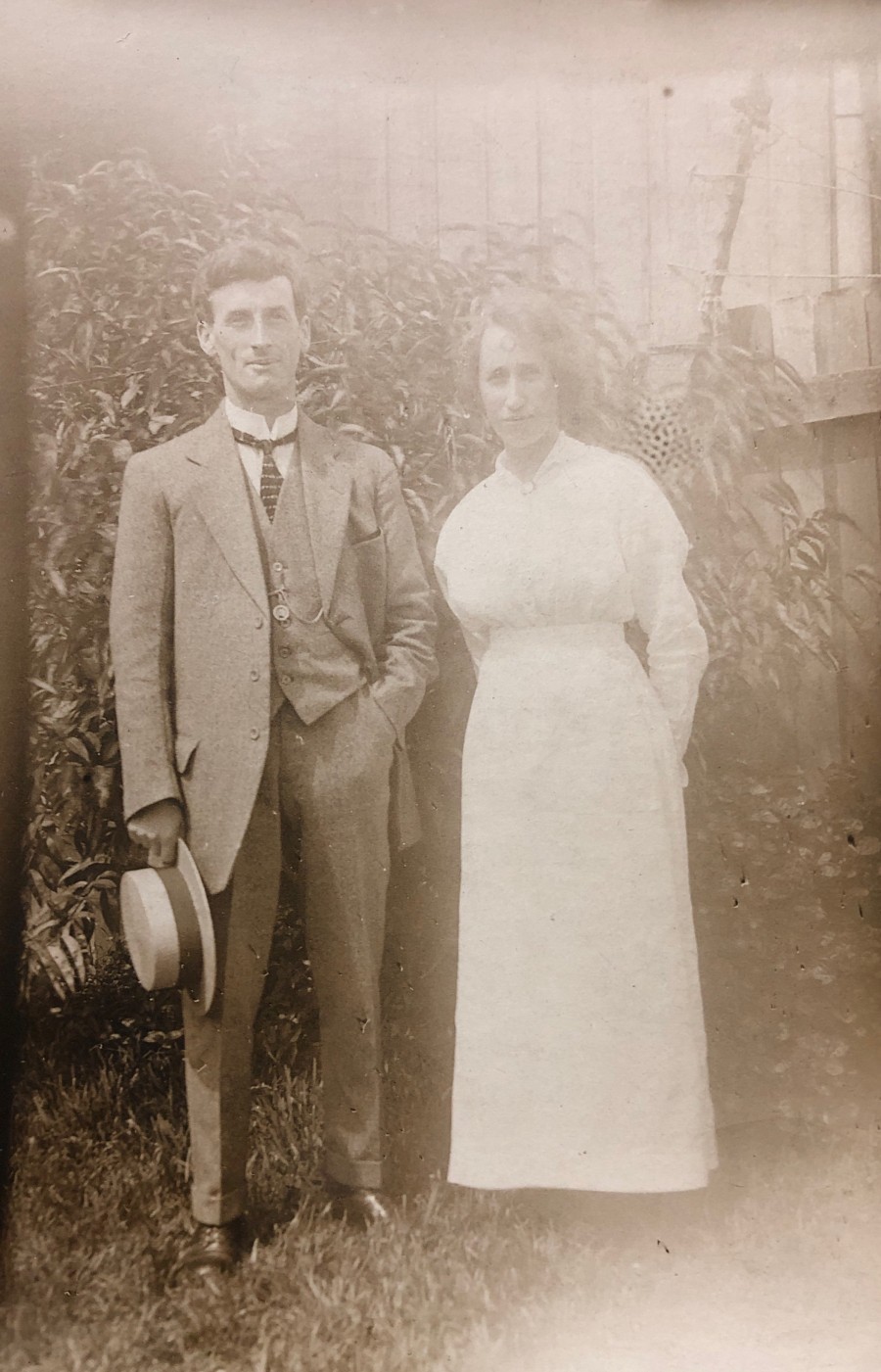

My father loved poetry. It seems he'd always loved it. One of his favourite poetry books was, 'An Anthology of Modern Verse.' On the inside of the front cover of his book, it says, 'To Michael, with best wishes, Faith. Christmas, 1934.' (Purchased from Dymocks on George St, Sydney). Faith lived down the street. Her brother was the best man at my mother and father's wedding in 1940. He was killed a few years later in the war. But Dad really liked poetry and would often quote it.

My father also used to sing. He used to sing Gilbert and Sullivan. Someone said to my father once that my brother Michael was a good singer. Dad said, "Oh yes, but not as good as me."

Dad was about sixty-five years old when he died. He had a heart attack. Mum called me and said, "Come and listen to your father breathing." He'd had a heart attack a long time earlier but he had recovered. The thing I remember about that is we all thought, oh he'll be fine. The ignorance. And Mum said, "It's all right for you but who will I have to talk to?" My parents used to talk a lot to each other.

I went in and walked straight out and rang the priest and the ambulance and mum said, "Is it that serious?" And I said, "Yes." The only reason I knew it was serious was from TV. I recognised that heavy, laboured breathing. His face was so calm. The priest arrived first and he gave my father the last rites. He said when he had finished doing it my father stopped breathing.

So when the ambulance came they attempted to resuscitate him but he was gone. At least he didn't look like he was in any pain. His face was nice and calm.

It took me about two weeks to really believe he was dead. I'd keep seeing people walking along the street in the sort of clothes he wore and for an instant, I'd think it was him.

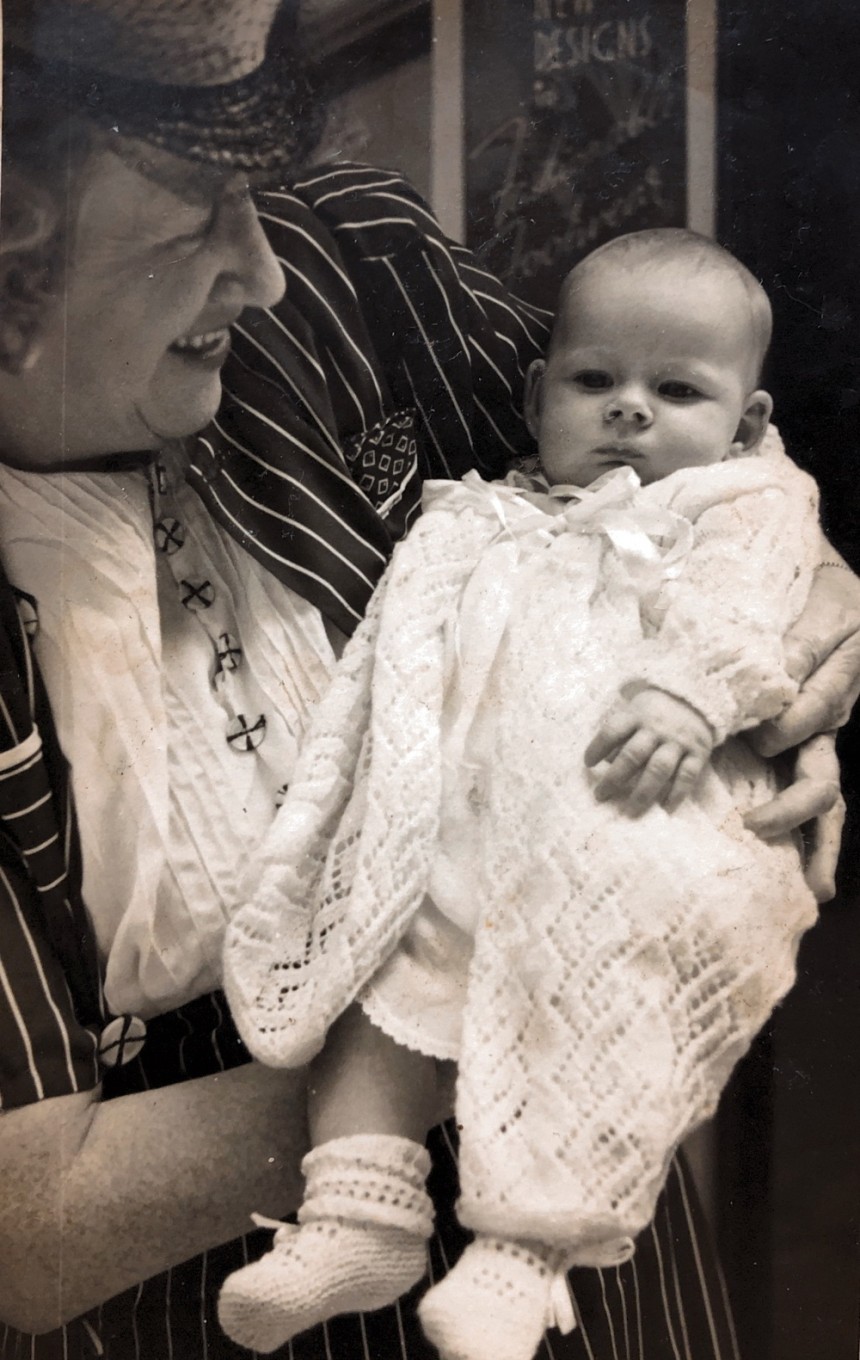

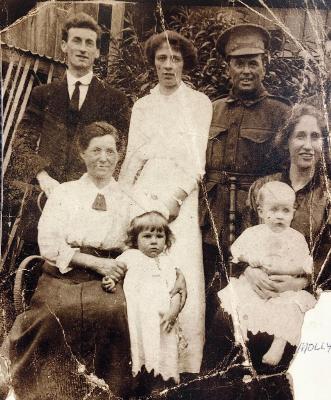

My Mother

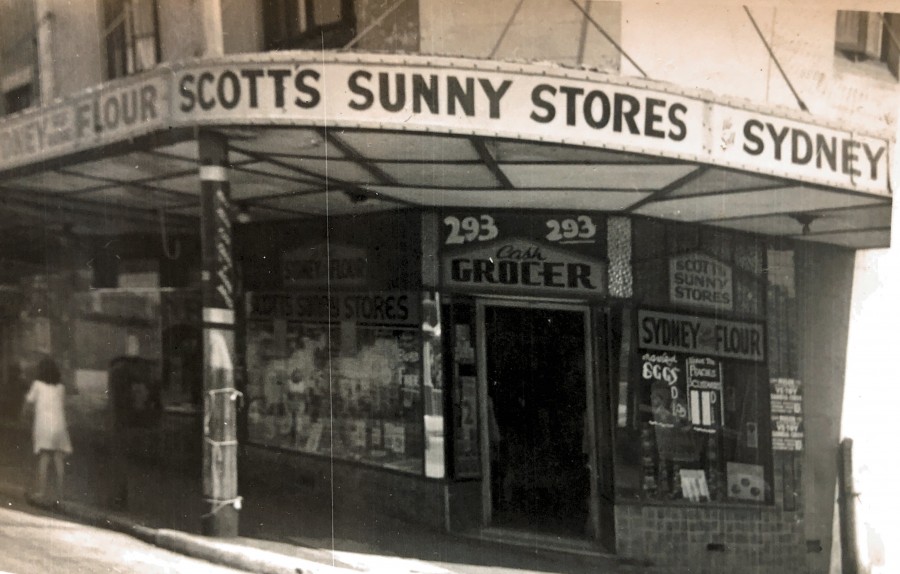

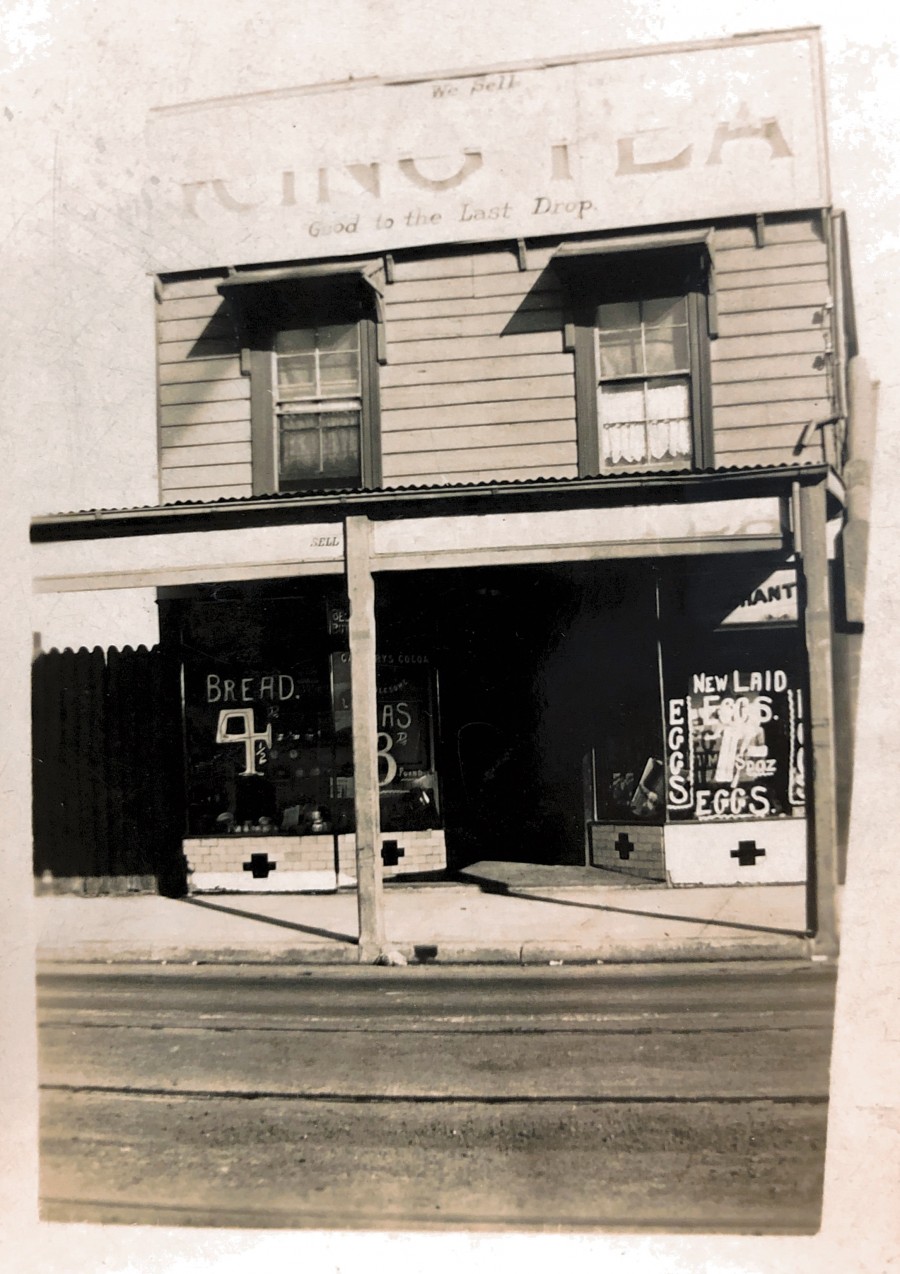

My mother was born Molly Scott. Her mother's name was Anne Veronica McGuiness and her father was Henry Scott, known as Harry. Together they owned a shop in Alexandria. Mum was an only child. She always wanted to have a number of children because she thought it was awful being an only child. So she did. In the end, she had five children – and she loved them all.

Mum had a very classical type of education. She attended Monte Sant' Angelo Mercy College in North Sydney. She was a boarder there. This was because her parents were busy running a shop. Mum was very musical. If you came and hummed a few bars of something from an opera she could tell you what opera it was – sometimes she could even sing the Aria.

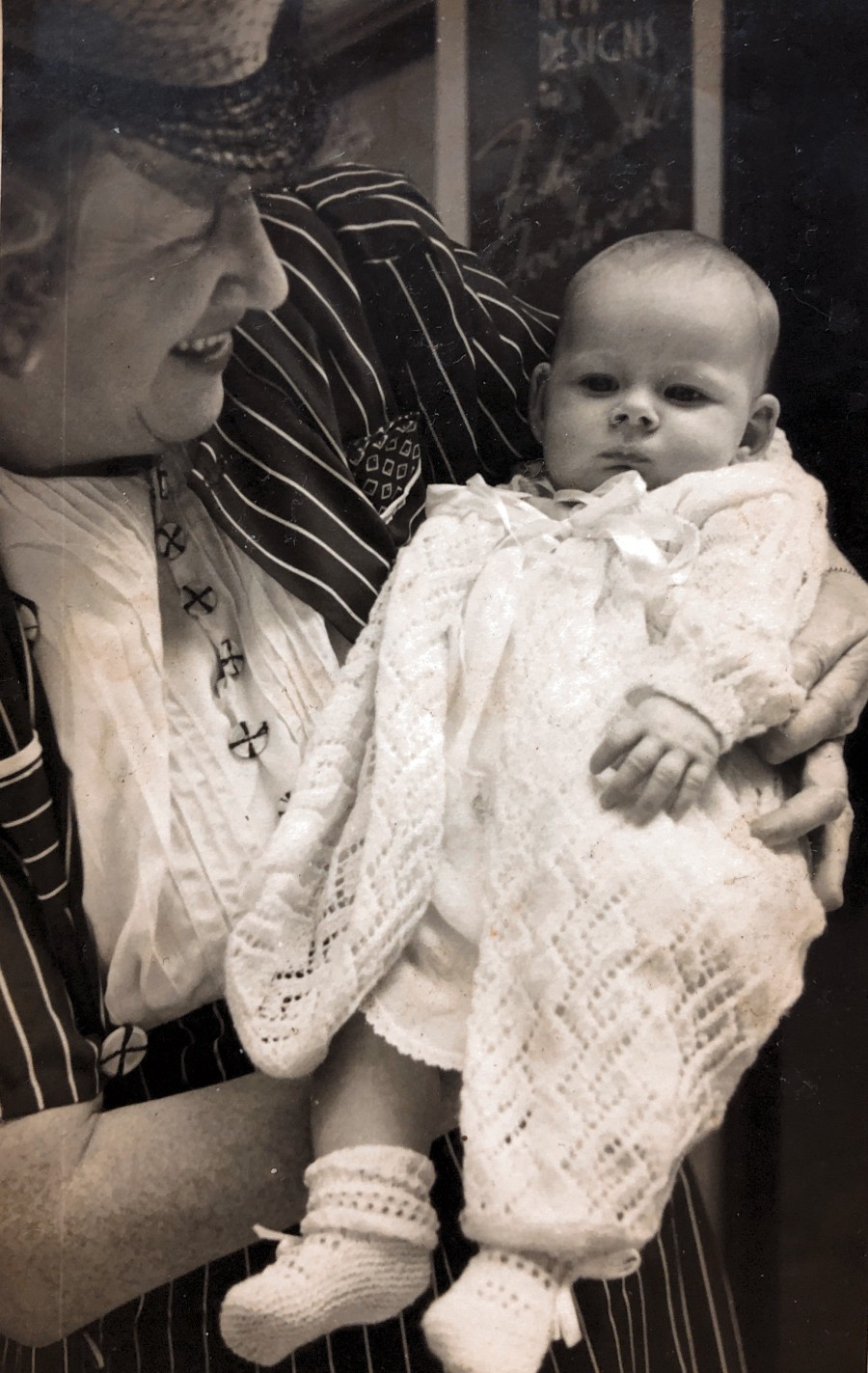

Mum was a great mother but she was much better with babies than older kids, for some reason. I don’t mean that you were loved any less, it was just that it was as if she didn’t quite know what to do with us when we were older.

My father had a heart attack and passed away. The next day my Mum had a job. The first time she worked, she worked in a grocery shop. I’m not positive about the order in which some of these things happened. Another job she had was at a hotel at Leichhardt, across from ‘Marketplace.’ I don’t know what she did there, specifically. She always had a job. Then she gained employment at the post office in Haberfield.

When she applied for the job at the post office, she worried about being too old, so on her application, she took ten years off her real age. They didn’t find out her real age until she was about seventy-two.

When Mum passed away, the Church was packed for her funeral. This was because all the people in Haberfield knew her. I remember a boy I went out with when I was young, believed that it was through Mum that he did so well at school. She had motivated him to study. Mum would encourage people to do things and to try new things. There was a lot of things that my mother did that were very good. Once she got very cranky with some Italian people. This was around the time in the 1980s when lots of Vietnamese boat people were arriving in Australia, seeking asylum. A lot of local people were complaining that it was too hard to understand the Vietnamese so they didn’t want them to be here. My mother was so angry because she said, “I have spent years working with people whose language is very hard to understand and I’ve never made any kind of complaint.”

Mum nearly always wore pants because she didn’t like the shape of her legs. There was a story of my father giving mum some money, telling her to go and buy some clothing and he said, “Buy a dress.” Later on, I had a dressmaker, who was the mother of two girls I taught. I got her to make some things for Mum that were done in a way that she liked. So she did have a few dresses then.

Mum was very kind. She brought us all up to help other people. She was a good worker, she was clever and she was musical. Mum loved her family. She loved her grandchildren.

Mum worked until her late 70’s. Then she became sick with early dementia. She didn’t want to go into a nursing home. So we bought this place I live in now in Ashfield and I looked after her. Physically, Mum was very fit. One of the things that happened was that Mum went somewhere and a woman in the street approached her and asked her where she was off to. Mum replied that she didn’t know. So the lady looked in Mum’s bag and there were details for the aged care facility at Concord in there.

So when I got home from teaching there were three cars from the aged care facility parked out the front of our place. Mum would go there to participate in programs and activities for people with dementia. She’d been there earlier that day doing some activities. They told me that she had to go into a nursing home. They said this because they felt that she was at risk of being run over or something I suppose.

I said to them, next week I’ll be on school holidays and so she doesn’t have to go yet." Their response was, “We’re not interested in you or what you want. She’s our responsibility.”

Anyway, it turned out alright, thank goodness because she didn’t go into the nursing home until the following January and she was at a nursing home nearby. I was able to go there of an afternoon, take her clothes home, wash them and then bring them back, take her for a walk. All of these sorts of things.

The funny thing about all of this was that I was the person she forgot. Once, she was upstairs and I was downstairs having a coffee and smoking. She said to me, “Do you work here?” I said, “Yes.” I discovered that when people start to get any kind of dementia, you don’t argue. If they’re wrong, tough luck.

When Mum went to the nursing home I cried for about six days. They wouldn’t let me visit there until she settled. After that, I started visiting. It was at Ashfield. It was a good nursing home. There were things going on. I went there and she was dancing and thought oh my God, good luck to her. Another time I went and they had Mum tied to the chair with a sheet. I said, “Why is my mother tied to a chair?" They told me that Mum and another woman got out. It seems Mum and this other lady left the place and they were found at Canterbury Station. They’d walked there.

That all worked out well. I could go there a couple of afternoons a week and on the weekends. I could do her washing. But then the people who owned the nursing home sold it. This is the horrifying thing – we were notified that my mother had been moved to a place in Greenacre. Anyway, I tried every single thing to get her moved somewhere else and all they would say to me was, “She is already in a nursing home.” That meant that I could only go on the weekends and in the school holidays. My problem with the nursing home there was that you never saw the same staff member twice. That’s the thing with a lot of these places. Therefore, people don’t get the medication they’re supposed to get because the communication between changing staff members is insufficient. I’d go crook at the staff there. I’d say, “Where did you get the clothes my mother’s got on? They're not her clothes." My mother was a small person and so I made sure that the clothes I had made for her fit her well. “It’s hanging off her. Obviously, they’re not her clothes. Get it off her now and put her own clothes on.” Then I said, “Take note of the fact that some of the clothes match each other and so they can go together to make a complete outfit.” Oh, I was dreadful. So I complained when things were wrong. I said, “After all, it’s my mother. That’s what you’ve got to remember.”

She was going downhill. Margaret and I were with Mum. We were there for a few hours. Margaret asked them if they thought Mum would die that night. They said no. So Margaret and I went home and then at five thirty in the morning I got a phone call to say she'd died.

Margaret came to the fore, doing most of the preparation for Mum's funeral, with the help of her friend. Margaret was always clever and able to do most things well. I admire her and her family - they are a credit to Marg and John.

So, my grandmother was the first person buried in this grave. Then when Dad died he was buried there and then mum was buried there. But the interesting thing about that grave is that the people at Rookwood told me that now I own no grave. There are four people in the grave already. What he said we could do is if we would like to be cremated they can put another six people in there if we want to. That's something that we don't think about much.

At Mum's funeral, when I was walking up the aisle to go out I saw this fellow. He was getting on in years himself. He lived near us in Ramsay Street when we were younger and he was crying and he said, "It's the end of an era." So everyone thought so highly of my mother. We did too of course.

Later Life

A number of years ago I'd been working quite happily teaching at St Joan of Arc School. Then I started getting things wrong with me. I had a few bouts with cancer. Luckily not related to each other. So I'm still here. I retired because I had to have operations. A year later I was better, for which I'm most grateful. So I then decided to do some voluntary work at school and one of the doctors said to me I should do some voluntary work at Concord Hospital. So I've continued those. I haven't always done exactly the same thing at school. Mostly, nowadays I do maths but sometimes some reading for them.

At the hospital, I take people to where they have to go, which is a good thing cause it's a sprawling place and people can get lost quite easily. Also, I quite often look after my neighbours’ children. I have done since they were quite little. His mother, Vanessa wrote to the council about all the voluntary stuff I do and I ended up getting a certificate on Australia Day. That was quite a beautiful thing for me.